LAGERWEY, J. & KALINOWSKI, M. (org.)

EXTREMAMENTE CONSOLADOR:“For help in financing translations and preparation of the manuscript, we are indebted to the Centre de recherche sur les civilisations chinoise, japonaise et tibétaine. A great debt is also owed our translators, some of whom received only token remuneration and some none at all: John Kieschnick, Regina Llamas, Margaret McIntosh, Sabine Wilms, Didier Davin and John Lagerwey. The same is true of Kimberly Powers, who contributed far more than the hours paid in order to bring the bibliography and index as close to perfection as possible.”

“The present work covers primarily the period from 1250BC on, when written materials first become available.”

INTRODUCTION

“After Kong Qiu (Confucius; 551–479 BC) and his disciples, defenders of traditional values and of a humanism based on education, ritual practice and moral amelioration, various schools of thought and wisdom developed and engaged in ongoing debates in the princely courts of the 5th to 3rd centuries BC.”

“The pantheon Wu-ding sacrificed to included such <nature> gods as River and Mountain, as well as Di (Lord), a god distinguished from all others by the fact that, like the Shang king, he <ordered> (ling), and by the fact he was not sacrificed to even though his powers would seem to have been extensive”

“Relying on the work of anthropologists and linguists, Kern underlines the <striking overlap between the language of poetry, the aesthetics of ritual and the ideology of memory> as expressed in these hymns.”

“The parallel with the Pentateuch and the Psalms as described by Artur Weiser is also striking: <The cult of the feast of Yahweh, the heart of which was the revelation of God at Sinai, was the native soil on which the tradition of the Heilsgeschichte concerning the Exodus, the revelation at Sinai, and the conquest of the land was formed and cultivated.> Through the ritual repetition of salvation history at the annual feast, it <became a new ‘event’. The congregation attending the feast experienced this as something which happened in its presence, and thereby participated in the assurance and realization of salvation which was the real purpose of the festival.> See Artur Weiser, The Psalms: a commentary, tr. Herbert Hartwell (London, 1962), p. 26, n. 2, and p. 28.”

“With the appropriation of the Annals by Confucius or his disciples, history writing bifurcates into <sacred> and <secular> traditions. Entries in the Annals were now understood as messages addressed not to the ancestors but to living contemporaries, and their stylistic particularities were interpreted as a politico-ethical commentary on the course of events. The Annals rapidly acquired the status of a canonical text, and the first commentarial traditions appeared. In the Zuo commentary, history became a mirror aimed at supplying members of the educated elite with a working knowledge of past events”

“In the Shang, the word wu referred at once to a divine figure, a kind of sacrifice and a person with a special status or function. The wu could also be used as a sacrificial victim. For the early Zhou we have no information, but the Rites of Zhou include a <chief shaman> in charge of male (xi) and female shamans (wu) who perform a wide range of rituals, including exorcisms, sacrifices and rain dances. Lin cites Warring States and Han texts that show the involvement of shamans in healing, divining, fortune-telling and black magic of various kinds.”

“O comentário do Zuo narra um conselheiro que pergunta a seu duque como expor uma <mulher tola> – sua maneira de se referir a uma wu – ao sol poderia ser útil para terminar uma estiagem. Xunzi se refere a xamãs machos e fêmeas, respectivamente, como <aleijados> e <corcundas>, sugerindo que fossem inatamente anormais ou desprezíveis. Han os ataca com ainda mais virulência. Para ele, os wu são figuras traiçoeiras e semeadoras de <práticas sinistras> (zuodao). Mas o retrato mais revelador da precipitação de seu status é transmitido por uma estória contida num dos capítulos iniciais do Zhuangzi. Liezi, discípulo de um mestre do Dao, encontra um xamã que crê ser ainda mais poderoso que o seu mestre. Este, ao tomar conhecimento do fato, convida o estranho para ter seu caráter mapeado por vários dias seguidas, em sua casa. Num processo [anti?]terapêutico que lembra a psicanálise, o mestre faz o xamã conhecer a si mesmo um pouco melhor a cada dia. Dá-se uma espécie de lavagem cerebral. O xamã não vê o Dao/Tao, mas apenas o que o mestre o revela, com cálculo. No último dia, o que o mestre o ensina é tão horripilante que o xamã foge para longe sem dar que Liezi pudesse reencontrá-lo. Humilhado e vencido, Liezi vai para casa e, pelos próximos três anos, toma o lugar de sua mulher no fogão e alimenta os porcos como se fossem gente.”[???]

“the literati of the ancient world had given precedence to the king over

the self, and valued subjection over subjectivity”

“one’s basic vital energy (qi)”

“vital essence (jing)”

Eleve seu ki para acreditar em Marx

Nem materialismo nem História

O que importa são as esferas do átomo

DEMOcitizen

Só depende de você o autocontrole

superpleonasmo

Ser herói não é uma condição heróica.

“A serena indiferença do Sábio às contingências do mundo exterior é louvada como o privilégio dos homens mutilados e amputados [castrados? História do eunuco? Toda a Academia descende dessa raça mística?]. Qualquer amputação é uma bênção: golpe de sorte que liberta.”

Nem Montesquieu, do alto de suas convicções, poderia negar que basta ao habitante da zona mais tórrida, simiesco e concupiscente que é, cortar fora o próprio bilau para se converter como que por milagre no nórdico mais glacial: o clima não tem poder sobre a engenhosidade do eunuco, cujo sangue não corre atrás de interesses “impuros”. E qualquer babuíno, por fortuna, pode ser um brâmane (um sem-pau).

O eunuco está livre para fazer política, isto é, intrigas.

UM PROBLEMA DE ENERGIA:“There is <no Cartesian opposition of mind and matter,> and intentionality, so central to Western reflection on the self as an <autonomous agent,> is irrelevant to the Chinese discovery of self as <a purely vital activity.>”

Para o bem ou para o mal, eu sou tão poderoso que o suicídio constituiria uma impossibilidade automática enquanto questão contemporânea (é um problema cuja solução pertence a um futuro que, momentaneamente, posso chamar de longínquo).

Seria um estoque, um todo de potência armazenado, no “nada” do meu entorno, que não encontraria destinação e não poderia ser simplesmente “evacuado” da realidade. Isto só seria possível mediante uma boa explosão atômica que tragasse tudo ao seu redor (meu mundo, meus lugares, minhas pessoas).

Assim como não é possível forçar uma máquina emperrada a seguir o movimento, seguir existindo.

“<White mind> is the title of a chapter in the Guanzi and refers to growing <closer to the spirit world> through self-cultivation. In general, whiteness and brightness refer to the spirit world, as in the terms <bright spirits> (mingshen) and <Hall of Light> (Mingtang).”

“One of the earliest medical classics, the Suwen (Plain questions), <proposes that in general all disease originates from the changes of the six qi and that physicians must observe the disease mechanisms and not violate the principles of the movements of the six qi.> Contemporaries, says the Suwen, <have lost compliance with the four seasons and go against what is appropriate in the cold or in summer heat.> Ghosts and demons do not disappear altogether from the medical classics, but they are seen above all as the cause of <withdrawal> [abstinência] and <mania,> that is, psychological illness. Even strange dreams are explained in physiological terms, as the result of fear caused by lack of blood and qi in the heart that leads to dispersal of the spirit when asleep.”

“the tales of Yao and Shun, two emperors of high antiquity said to have transferred power to virtuous ministers rather than to their sons, show how the <end of kin-based empire brought into conflict heredity and talent.>”

“the word Dao refers to absolute generality that is infinite extensiveness (…) Being without definition, it does nothing and, without doing anything, there is nothing that is not done.”Levi

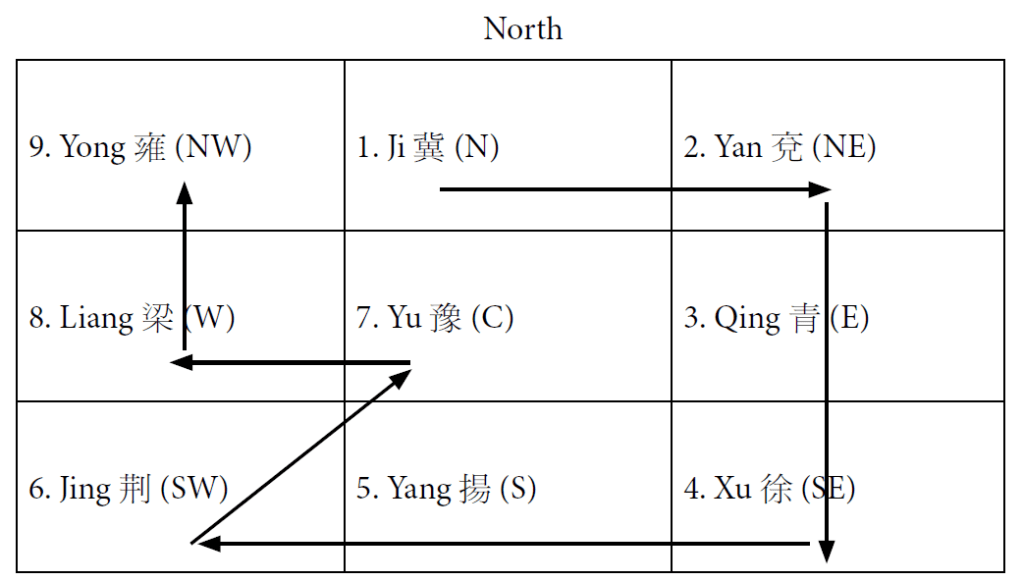

“Described as having four faces and being the <unique man,> the Yellow Emperor embodies sovereignty over space-time by virtue of his occupation of the center, that is, his <domination of the four directions from a strategic point which does not belong to ordinary space>: like Heaven in the archaic sacrificial system and Dao in the new philosophical system, the center is transcendent.”

“Confucius [is] <the most important mythic figure of all, prototype of the worthy scholar who fails to find a worthy ruler to employ him.>”

“In this new supreme cult, the Yellow Emperor was shifted to the southwest, corresponding to the <middle> of the year, and Taiyi took his place in the center.”

“The bureaucratic empire simply could not be built on ancestor worship, not even of the <purely symbolic> kind the Ru sought to impose on the Son of Heaven: it required worship of an abstract, impersonal and universal kind that only the new qi-based cosmology and calendrical astrology could provide. It is this radical and ongoing transformation of state religion in the Han that explains why, as Fu-shih Lin shows, the wu, who still enjoyed official positions under the chamberlain for ceremonials in the Western Han, were in the Eastern Han shifted into the domestic treasury, <in charge of the small sacrificial rites of the palace>: the old, anthropomorphic religion was dead.”

“It is not surprising that immortals and hermits, both associated with the mountains and wild areas just beyond the city and clearly distinguished from the state-sponsored exemplars on the sacrificial registers, became local benefactors and the deities of cults devoted exclusively to the well-being of a specific town or small region. In the stories, the recurring theme of tensions with kings and high officials likewise expresses the particularist, local nature of many of these cults.” Lewis

“a religious culture is unveiled in which sacrificial goods are quantified in terms of tribute or conscript labor, a society where status was defined in terms of ritual expenditure and where piety to the spirit world was translated into a detailed complex of material symbolism ranging from the measurement and value of ritual jades to the color and flavor associated with the cuisine offered up to the spirit world and shared in ritual banquets.” Sterckx

“The Discussions, which recounts the court debate of 81 BC over the establishment of state monopolies in salt and iron, reveals a fundamental contradiction between the emerging state market economy and its theoretical ritual framework.”

“Shall we sacrifice one hundred Qiang people (a nomadic enemy tribe) and one hundred sets of sheep and pigs to (High King) Tang, Great Ancestors Jia and Ding, and Grandfather Yi?”

“sacrificial provisions rank first among nine types of tributary goods to be collected by the feudal state.”

“While Mozi [creator of the Moists credo] called for simplicity in funerals and mocked the rival Ru as funeral specialists primarily attracted by the food they could eat while performing, Guanzi thought lavish funerals were good for the economy. Starting in the Warring States era, lists of grave goods were meticulously compiled and inserted in the grave. <Spirit artifacts> came to be mass produced: according to Sterckx, a kiln [fornalha] near Chang’an could fire 8000 items at once.”

“Do the <daybooks> (rishu) discovered in such numbers in Qin and early Han tombs represent a religion common to all, or should we speak of an <elite common religion>? Mu-chou Poo and Liu Tseng-kuei draw heavily on these new sources, and both authors agree that they are, to cite Liu’s conclusion, <the complex product of popular belief and the theory of interaction between heaven and humans.> That is, they very clearly belong to their times, when widely shared—and inevitably elite—theories of the mutual influence (ganying) of humans and nature required of people that they adapt their behavior to the natural cycles of seasons and months, but also ensured that, without the help of any religious specialists, people could have a very real impact on their fate. Liu therefore concludes that <people needed only to master its rules in order to enjoy space to act and to choose whether to go toward or to avoid. They could even use methods that converted the inauspicious into the auspicious.>”

“The Red Emperor (Lord), who is probably identical to the Fiery Emperor mentioned by Lewis and Kalinowski, is a god in charge of punishment, so on days when he <approaches> —descends to earth—people should stay home and avoid purposeful activities. Seven days before the annual sacrifice to all gods in the eighth month, people should not visit families who were in mourning or where a child had just been born. There were taboos on pronouncing the word <death> or <to die,> and graves were called <homes for ten thousand years.> Avoidance of the death date and name of the deceased were already generalized, and this at once ensured the divine status of the dead and kept them at a distance: <The living belong to Chang’an, the dead to Taishan.>”

“It would seem, then, that, contrary to the popular image, Han festivals were not at all about carnival-like joy for a good year. Seen through the lens of the taboos, it was about being careful to the utmost lest one commit a fault. Festivals were times of crisis, and the taboos were rules for getting through the narrows. Not only did people worship the gods with sacrifices at this time, they often avoided disaster by not going outdoors and did their best not to disturb the yin, yang and five agent energies. This is reminiscent of the way the Han handled natural catastrophes. For example, on the two solstices, officials did not handle public work and military movements were halted.”

“The discovery of tens of thousands of Qin and Han tombs and the painstaking work of archaeologists on these tombs has contributed substantially to our understanding of the importance of the funerary culture of the early empires. As Michèle Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens puts it, <We may say that the tombs, their décor and their furnishings together constitute a compendium of the cosmological beliefs, the conceptions and the rites linked to death, but also of the myths, divinities and demons that peopled the Han imaginary world.> Like the study of political institutions, that of funerary culture identifies the last century of Western Han as a major turning point, with the appearance of the custom of burying husband and wife in the same tomb and the emergence of the house-tomb—purely symbolic until the 2nd century BC—as the universal mode of sepulture. What the latter implied in religious terms was the primacy of tomb over ancestral temple and of the individual over the clan: what more telling illustration could be found of the dramatic changes that had occurred in Chinese society?—the collapse of Zhou rites and music gave way not just to a bureaucratic empire ruled by a mystified Son of Heaven, but also to a world of individuals whose memory could be perpetuated as had been, in the past, that of founder ancestors like Houji or sage kings like Yu. This is, therefore, the time to refer to the invention of the biography by Sima Qian (ca. 145–90 BC) which, according to Yuri Pines, <epitomizes a change of mentality from the lineage-oriented to an individual-oriented notion of continuity and immortality.> To Sima Qian, who in his autobiography compares himself to Confucius, it was also about the righting of injustice: the historian, by his judgments, could reverse the injustices of history. In sum, the new literary genre conjoined concerns about justice and immortality, ethics and <survival.>”

“Like Taiyi in the Han, this Lord of Heaven is linked to the Big Dipper, which on occasion serves as his chariot. The prevalence of Xiwangmu (west) in the company of her rather unimpressive <mate,>Dongwanggong (east), in 2nd century AD tombs is likewise a reflection of the rising impact of cosmological thinking.”

“One of the more interesting features of these steles [monólitos] is the genealogies they contain, which usually mention a distant first ancestor, then jump to ego’s near ascendants”

“By <alternative forms of knowledge>Espesset means the so-called chenwei <weft> [tramas, entrelaçados] or <apocryphal> texts, but also the sudden appearance of revealed texts like the Taiping jing (Scripture of Great Peace).”

“They are at once reflections of a bureaucratic empire in which clan solidarity and ancestor worship had at least in part given way to the worship of immortals and sage kings and of the <eschatological preoccupations> generated by the gradual disintegration of the empire in the 2nd century AD.”

Shennong bencao jing (Materia medica of the Divine Farmer)

“Ghost infixation is a disease that was passed on from a dead person to a living person through contagion by hidden corpse qi, in severe cases to the point of killing off entire households.”

“inherited burden (chengfu)”

“First, the traditions of moral introspection that had been developed in the self-cultivation texts had provided an opening for a sense of guilt. Second, the ancestors had become individualized along with the rest of society in the Warring States. Third, ancestors were no longer the charismatic founders of states, they were the recently dead of local families. But what the ancestors had lost in political they had gained in psychological power because, the process of interiorization continuing to do its work, it had led to the discovery of the self as a place where ancestral dramas also continued to play themselves out to their inevitable conclusions: justice in the form of retribution (bao) was inevitable.”

“The art of delivery from infixation, fundamentally different from acumoxa and medicinal therapy, consisted in presenting petitions to confess one’s own and one’s ancestors’ sins … (Infixation disease) was all the more threatening to people because the family was at its core, and the disease attacked and spread within the household.”

“Many of the chapters here, but especially those of Eno, Kern, Cook, Levi and Li enable us to give a nuanced historical gradation and, above all, to see early Chinese ancestor worship for what it was: an expression of political power and legitimacy that was by definition sumptuary and therefore emphatically not an integral part of some kind of universal, unchanging Chinese religion.”

“The third point worth underlining is the notion of <religion> itself that this book, with its multiplicity of disciplinary approaches, assumes, namely, that religion is more about the structuring values and practices of a given society than about the beliefs of individuals. The place allotted the individual is in any case of necessity small for the early period of Chinese history, for want of sources. Here, it is only in the chapters of Graziani and Csikszentmihàlyi on self-cultivation that, timidly, the individual practitioner appears—and we learn that the aim of such individual practice is to interiorize traditional ritual attitudes or to become a sovereign subject in union with an impersonal Dao.”

“We have already mentioned how Li Jianmin’s article points toward the disjointed future that will be the subject of the next two volumes. This reminds us that the larger project is less about some stable system we might call <early Chinese religion> than it is about the periodic collapse of such systems and how, from the disassembled fragments of the old something radically new is laboriously constructed, thus providing a social and psychological foundation for the next phase of political integration. In the pages above, we have isolated rationalization and interiorization as the two fundamental strategies of the practice of reconstruction. We apply them here to our analysis of the central period of historical change covered by these volumes: the Warring States. The two volumes to come will apply them to the next period of political disarray, the Six Dynasties.”

“The most determinedly historical/material approaches are quite logically those of the archaeologists, for the discipline of archaeology consists in constant training in patience, in not rushing to judgment, in trying to let new materials speak for themselves as much as possible rather than forcing them into a pre-existent theory. Given the ever-growing impact of archaeology on the field of ancient China studies, it should hardly come as a surprise that this same prudential attitude oft en characterizes essays that use the new manuscript materials. It is to this necessary prudence that we have spoken above in our methodological introduction. On the other end of the scale are chapters by authors like Kominami and Levi: the first makes use of a traditional philological approach that reads texts of widely different

periods as part of a single <book>; the second makes use of recent anthropologically inspired studies of sacrifice in ancient Greece to read texts such as the Rites of Zhou that all agree are late idealizations but that Levi parses anew in order to find his sociological way back into the heart of early Zhou ancestral sacrifice. Whether or not the audacious conclusions of these two authors win widespread acceptance, there can be no doubt but that their ideas merit the debates they will inevitably occasion.”

SHANG AND WESTERN ZHOU (1250–771BC)

SHANG STATE RELIGION AND THE PANTHEON OF THE ORACLE TEXTS

*

ROBERT ENO

“the oracle texts are virtually the only written legacy of any Chinese era before the armies of the Zhou brought the Shang dynasty to an end about 1046 BC. (…) These dates continue to provoke strong debate among scholars, and no proposed dates for China prior to 841 BC may yet be considered authoritative.”

“China came late to writing, and the Shang, which established dynastic power about 1600 BC, was preceded by a range of cultures, known through the archaeological record. During the 3rd millennium BC, some of these exhibit a scale of material distinctiveness, urbanization and social complexity that suggests development toward state formation and regional civilization.”

Xiaoneng Yang – New perspectives in China’s past: Chinese archaeology in the 20th century, 2004 (artigo “Urban revolution in the late prehistoric China”, pp. 99-143).

“When we look to the oracle texts for information about China’s religious past, we must bear in mind that the Shang may be only one of many ancestors of Chinese civilization.”

“It is tempting to view the Liangzhu culture, with its broad regional reach over territories that seem subject to political coordination from a series of central places, as a <civilization>, in Norman Yoffee’s sense of an ideology and culture for which the sustaining of a state is its principal raison d’être (Myths of the archaic state: evolution of the earliest cities, states, and civilizations [Cambridge, Eng., 2004], p. 17).”

“Liangzhu culture disappears from the archaeological record quite suddenly, and the successor culture that comes to occupy the Yangzi delta region exhibits none of the advanced features of the Liangzhu polity. Virtually simultaneous, the established Longsha culture that had spread over the 3rd millennium from Shandong through the Central Plain left the Shandong region, directly north of the Liangzhu cultural horizon, to be replaced by a culture exhibiting far fewer features of development toward state structure.”

“The field of oracle bone studies tends to be highly specialized, in part because reading the texts requires specialized training and the volume of texts to be explored is very large, but also because the Shang art of divination by bone and shell involved many facets, each subject to elucidation by modern technical scholarship.”

“Dong was also the author of the first systematic overview of the texts, organizing them chronologically and building structures to allow systematic analysis in his 1945 work, Yin lipu (…) In the West, the indispensable tool that has educated scholars in the field has been David Keightley’s 1978 monograph, Sources of Shang history: the oracle bone inscriptions of Bronze Age China.”

“the dominant position in the early China field from the second quarter of the 20th century was occupied by a school of thought known as yigu, or <doubting antiquity,> characterizing a skeptical view holding that most received accounts of the distant past were in fact post-Qin fabrications or deliberate distortions, serving various interests of their authors or of the imperial state.

In recent decades, accelerating during the 1990s and the current decade, archaeologists have found in pre-imperial tombs dated as early as the 4th century BC caches of texts that match received versions that the yigu approach had maintained to be of much later date. The cumulative force of these discoveries has been to raise the credibility of attempts to interpret archaeologically recovered evidence in terms of the historical outlines drawn in received texts. The 1995 publication by Li Xueqin signaled that the skeptical methodology of mid-20th century scholarship was no longer a dominant trend in China.” “Li Xueqin, Zouchu yigu shidai (Shenyang, 1995). Li’s book is basically a collection of previously published studies, but the lead essay, which shares the title of the book, constitutes a manifesto rejecting as passé the methodologies of the yigu approach. This paradigm shift, if it may be so termed, has had varying impact outside of China, and some scholars in the West remain wary of correlations between archaeological evidence and the testimony of received texts. For a pronounced example, see Robert Bagley, <Shang archaeology,> in Cambridge history, pp. 124–231.”

“the impact on the field of the Chinese government’s commissioning of the research as a government-sponsored project, involving scores of scholars under deadline to produce an absolute chronology within a short time frame, and the acrimonious debate that has ensued over the specific chronology that the project adopted.”

“Since the 1970s and accelerating in recent years, the archaeological recovery of a very large corpus of Warring States and early Han manuscripts written on bamboo, silk and wood, has created increasing interest in paleographic studies, and this has benefited the field of oracle bone studies, where new materials have not been frequently added to the existing corpus, and also Zhou bronze studies, where new inscriptions continue to be published in great numbers. The recent translation into English of Qiu Xigui’s massive 1988 text on paleographic principles and

methods, Wenzixue gaiyaois a reflection of this trend”

“Oracle texts exist as inscriptions on <oracle bones,> ox scapulae and turtle shells that were used for divinatory purposes. Virtually all known Shang inscribed oracle bones have been excavated from a region near Anyang, in northeast Henan, which was the site of the last capital of the Shang state, generally referred to as Yinxu, occupied as the royal central place from about 1300 BC until the Zhou conquest.” “The shape of the cracks or the sounds made in cracking constituted the data elicited by the diviners. Subsequently, a trained scribe carved on the obverse (and sometimes the reverse) a notation of the issue divined (known as the <charge>).”

“(I) a preface, including a date and the name of the individual presiding over the divination act; (II) the charge, that is, the topic of divination; following the charge, there sometimes may be a record of (III) the king’s prognostication, and in a subset of these cases, (IV) a verification of the ultimate outcome of events (if this element is present, the king’s foreknowledge is as a rule confirmed); finally, (V) a postface, noting the time when the divination was made (month of the year or year of the king’s reign) and, if the divination was made at a place remote from the capital, (VI) a notation of that place, may end the inscription. The vast majority of oracle texts conform to this template, although very few include all of them.”

Não é que eles tenham um talento fora de série para escrever verdadeiros calhamaços em superfícies microscópicas – uma adivinhação é muito mais sucinta do que parece, mesmo se dividindo em tantas seções:

“Cracking on (gui)hai¹ day, Zheng divined/

about whether the coming week would have no disaster.²/

The King prognosticated saying, <There will be disaster.>/

On the week’s renshen day a disaster occurred at the Zhong [encampment./

Fourth Month. (HJ 5807)”

¹ Último dia da semana do ciclo sexagenário chinês – intuível de acordo com a data prescrita para predições para semanas subsecutivas, por mais que os caracteres para gui estivessem perdidos na inscrição.

²“Current practice in China tends to employ the question form [Will there be any disaster during the upcoming week?], while in the West, statements are more usual”

“The possibility exists that divination by scapulimancy [vide glossário no começo] involved complex liturgical formulas, such as those preserved in texts dating from the Warring States era, that were not represented in the <bureaucratic> notation of the oracle texts”

NADA SUI GENERIS: “there existed a general rule that scheduled cult was offered to ancestors on the days of the week corresponding to their temple names.”

Keightley – Shang divination and metaphysics (1988)

“The periodization of oracle texts reveals substantial changes over the period from the reign of the earliest ruler to have bones inscribed, Wuding (r. ca. 1250–1192), to that of the last Shang king, Di-xin (r. ca. 1075–1046), known in later texts by his personal name Zhou.”

“The term <pantheon> is misleading if it is construed in parallel to, say, the Greek or Egyptian examples, which include a relatively fixed dramatis super-personae, predictably deployed in myth and art as well as worshipped in cult. Such a Chinese panoply may be suggested by myths recorded in much later documents, but not by the oracle texts. In this context, the term <pantheon> refers only to an inventory of significant spirits implied by oracle text references.”

“Pantheon members in category (A) were ancestors of the Shang royal house whose spirit tablets stood on the altars of the Zi clan temple complex at the Shang ritual center. For us, the best-known individual among them would be the king that the oracle texts call Da-yi and whom later received texts call Cheng Tang, the leader known for his overthrow of the Xia ruling house, establishing Shang dynastic control sometime about 1600 BC. (…) But Cheng Tang was not the founder of the lineage association to which all Shang kings belonged. The lineage was established six generations earlier by an ancestor known in the oracle texts as Shang-jia” “Shang-jia and the five succeeding first-born clan leaders form the earliest stratum of what may be called the core lineage.” “Although the oracle texts indicate that worship of pre-dynastic and dynastic kings shared many features, and, in particular, that Shang-jia was a focus of lineage cult, the other Pre-dynastic Kings are treated as relatively minor figures.”

“According to the Shiji, the founder of the Zi lineage was Xie, who was seven generations senior to Shang-jia (Zhonghua shuju, ed., 1. 91–92). However, judging from the oracle texts, ancestors prior to Shang-jia do not seem to have been represented within the temple shrine complex. It may be that the Shang ruling house saw itself as a branch of a larger descent group possessing the Zi lineage name (xing), of which Shang-jia was the founder.”

“As we see from (2), Pre-dynastic Kings could influence weather and crops, but this seems not to be true for dynastic kings and royal consorts. All ancestors could, however, affect the king’s person and outcomes of events in the human sphere.”

“<Former Lords>: Some figures in this group are, indeed, clearly historical, the most prominent example being Yi Yin, known through later texts as the chief minister to the dynastic founder Cheng Tang.”

ZOOCORNO: “According to the Shiji account, Ku’s secondary consort gave birth to Xie, the Shang lineage founder, after swallowing the egg of a dark bird.”

Melhor o primeiro mortal duma província do que um deus-súdito (segundo no “Olimpo”).

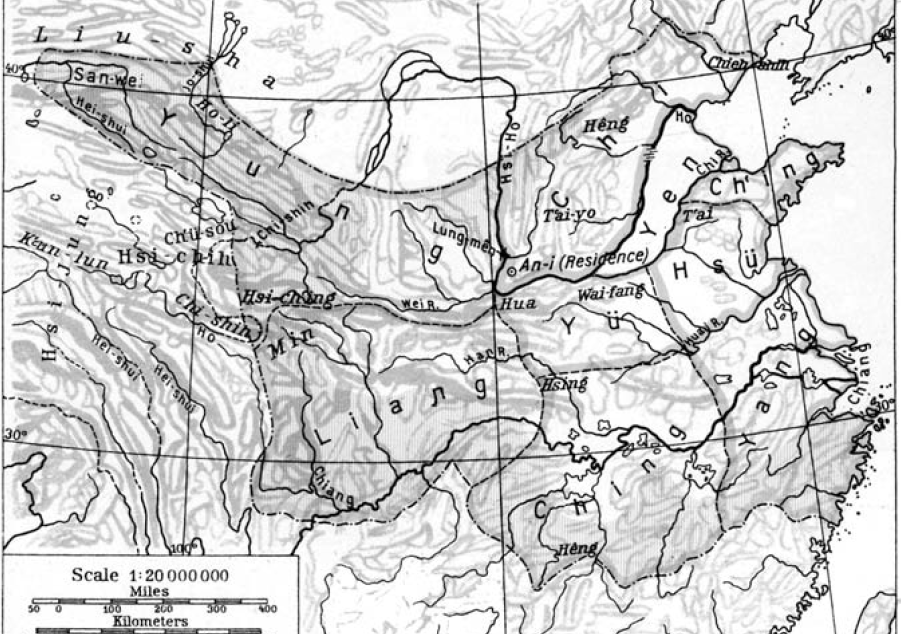

“By far, the most prominent figures in this sector of the pantheon are the Powers He, or the River Power, and Yue, or the Mountain Power. These are generally interpreted to denote the Yellow River and Mt. Song (Songshan), the major peak in the central Henan region of the Yellow River Valley, in the vicinity of the capitals of the Shang state prior to the move to Anyang ca. 1300 BC, roughly 50 years before the earliest oracle texts.”

“The parallel sequencing of the three Powers suggests the possibility of an imagined descent line that extends back to Natural Powers, passes down through the Former Lords, and ends in the core royal lineage.”

“There is evidence to support the inclusion in this group of a Sun Power, an Earth Power, Powers of the Cardinal Directions, Cloud and Wind Powers, and a number of others. However, there is so sharp a drop off in the volume of inscriptions, compared to the River and Mountain Powers, and the ambiguities of text interpretation are so plentiful, that it is possible to argue that no other phenomena of nature may have been conceived as Powers possessed of responsiveness and intent, or that membership of other Nature Powers in the pantheon may have been transient and unstable.”

“On the primary interpretation offered here, the rising and setting sun (or more likely a single Sun Power at rising and setting) is receiving cult. But it is equally possible that the ritual is to be done at sunrise and sunset, with the object unspecified (not unusual)”

“The well-known myth that in high antiquity there were ten suns, nine of which were shot from the sky by <Archer Yi,> invites association with the Shang calendar of the ten-day week, denoted by cyclical signs corresponding to ancestral cult schedules. Sarah Allan(*) has argued that Shang ancestors were <totemically identified with one of the ten suns,> and that the history of the lineage was expressed through this myth.”

(*) Shape of the turtle, p. 56.

Keightley – Graphs, words, and meanings: three reference works for Shang oracle-bone studies, with an excursus on the religious role of the Day or Sun (artigo)

______. – The ancestral landscape

“The graph for the soil, tu, is often interpreted by scholars as representing an Earth Power. Again, the evidence is characterized by ambiguities. In almost all cases of the occurrence of tu, the graph may be interpreted without reference to a Power, as referring to territory or as representing the term she, which would denote, by analogy with later practice, the major outdoor sacrificial altar at the Shang capital site.”

“Shang building foundations and interior sites are studded with pits in which animal and human victims were buried in sacrifice; whether the intended objects of sacrifice were spirits of these places, or whether these deaths were understood as general rites of sanctification is difficult to determine.” Era pra escoar a água da chuva…

Estrelas não eram endeusadas.

“The term Di is a part of all later religious traditions in China. It is used broadly as both a generic term for high spirits and earthly rulers. The distinctive role of supreme spirit is often signaled in later texts by the term shangdi (High Di), but in the oracle texts this usage is rarely seen.”

“the number of texts that point toward a model of a bureaucratized pantheon is far too small to support any strong claim for it as a feature of Shang religious imagination (<Was there a high god Ti in Shang religion?>Early China 15, 1990, p. 4).”

REDEFININDO A MARRA DE JEOVÁ: “Di, or Tian, was too remote for living humans to sacrifice to directly. Instead, an intermediary, such as an ancestral ruler, was necessary to convey to Di the offerings of the living.”

“a substantial number take the position that the term Di is an alternative way of denoting the first ancestor of the Shang, Ku, who is referred to in later texts as Di Ku.”

“The astronomical significance of the alignment of major structures at the Shang complex at Anyang has been argued in great detail in a series of articles by the archaeologist Shi Zhangru, published in the Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica (BIHP). For his hypothesis that the gaitian cosmological model influential in later eras is an artifact of Shang astronomy, see <Du ge jia shi Qiheng tu, shuo gaitian shuo qiyuan xinli chugao>” “Pankenier notes that the true Celestial Pole lies in a region of the sky that is vacant of significant stars—<Pole Stars> are simply those nearest to this vacant apex—and suggests that for the sophisticated observers of the Shang, the location of the true pole was of critical importance. He illustrates how the oracle text graph for Di can be projected on the north polar region of the ancient sky in such a way that its extreme points correspond with significant visible stars, while the intersection of linear axes at the center will map to the vacant Celestial Pole.”

“My own research has suggested a different direction for interpreting the status of Di in Shang religion. I have focused on the unusual distance that seems to exist between Di and living humans in the oracle texts, and explained it with reference to features of ancient written Chinese that provide no distinctions among singular, collective and generic nouns. My proposal is that the term di is used as a generic or collective term, assignable to any one Power or denoting groups of Powers, or all Powers, collectively, and that the Shang pantheon thus does not, in fact, possess an apex uniting its various segments.”

“This accounts for the use of the term generically to designate the deceased father of a king ruling as his immediate heir. It also suggests that the collective term may not include Powers that are not related to the core Shang lineage, descending from Shang-jia, or perhaps from the extended lineage, including figures such as Kui and Wang-hai.”

“The[re are] inscriptions (…) [that] are an obstacle to acceptance of the hypothesis of di as a collective term.” Cf. Michael J. Puett, To become a god: cosmology, sacrifice, and self-divinization in early China, Cambridge, Mass., 2002.

“in matters of state, such as ensuring good harvests and success in war, the king held a monopoly on oracular privilege.”

“in the case of the king’s prognostications, verifications in the Huayuanzhuang corpus confirm the Prince’s power to foretell, though they are rarely recorded.”

“it is only in the Early Era that we see the full pantheon active in the inscriptions. For example, by rough count, Di appears in Later Era texts with about one-seventh the frequency of the Early Era and the proportion for the River Power is comparable. By Period V, these Powers have virtually disappeared from the pantheon, as visible in the oracle texts.”

“Given that Period I texts account for almost 60 percent of the corpus recovered to date, while representing, at most, 30 percent of the duration of the oracle text era, it seems reasonable to view Wu-ding as a ruler with an unusually heightened concern about the spirit world, and one likely to encourage an expansive view of its population and of the king’s responsibilities in relation to it.”

Keightley – History of Religions 17.3–4 (1978)

______. – The making of the ancestors [tendências weberianas de análise (a burocracia do Estado chinês)]

“If we associate bureaucracy with activities that require complete predictability and hierarchical structures, and that stipulate in writing certain types of expectations, the oracle texts certainly evidence these in increasing degrees. The taxonomic impulse seems to grow throughout the corpus.” But: “Hierarchy without functional distinction and impersonality that assigns all importance to ascriptive features may in many ways be inimical to bureaucracy, using that term strictly.”

“The most celebrated example of subordinates to Di, the <Five Ministers of Di,> or <Five Great Ministers of Di,> appear on no more than three bones datable to Period I and one datable to Period III. Other inscriptions directly suggesting Powers subordinate to Di are equally rare; for example, the much quoted designation <Di’s Envoy Wind> appears only once. The notion that Di acted as the chief executive of the ancestral sector of the pantheon is also not well documented. Its chief support is Di’s appearance in a single inscription set, discussed earlier, where he is the apparent senior

figure in a hierarchical rite of hosting. Given these problems, the only hierarchy that we may assert to have clear definition in the oracle texts, becoming more profound as the corpus evolves, is the age-based hierarchy of the ancestral pantheon. While this type of hierarchy may be impersonal, in the sense that in the oracle texts we sense no idiosyncratic character features among the ancestors, it is deeply personal in that it is based entirely on ascriptive traits of lineage association, typical of kinship-based patrimonial organization and antithetical to the social impersonality that distinguished bureaucratic organization.”

“Powers controlling natural phenomena include Di, Nature Powers, Former Lords, Pre-dynastic Kings, and even in one case, the Dynastic King Da-yi, whose reach beyond an expected role may reflect the force of the state founder’s personal charisma.”

“It is certainly true that when Wu-ding’s tooth ached, only ancestors heard the report, and we might conclude that when the oracle texts worry about whether the River Power may <harm the King,> they are concerned with the king’s state interests, rather than his physical person.”

“questioning here whether the pantheon exhibits proto-bureaucratic features is not to dispute Keightley’s assertion that divination practice itself reflects the emergence of preconditions for bureaucratic state structures, which seems profoundly correct.”

LEIS RUDIMENTARES DE PRESCRIÇÃO DE DOCUMENTOS NA ARQUIVOLOGIA ORIENTAL! OS “70 ANOS” RITUAIS DOS CASCOS E OSSOS:“Zhang Guoshi proposes that the untidy <filing> method adopted for these materials—burial in pits—was the point at which their creators consigned them to the spirits in a gesture of sanctification”

“The question of when writing emerges is an unsettled one. In 1993, publication of an inscribed shard from the Longshan site of Dinggong in Shandong Province seemed to confirm a mature system of writing about a millennium earlier than the oracle texts (though one that bore no clear relation to Shang script); however, Cao Dingyun has convincingly demonstrated that this was very likely a fraud (<Shandong Zouping Dinggong yizhi ‘Longshan taowen’ bian wei>, Zhongyuan wenwu 1996.2, 32–38).”

“In Pankenier’s view, a Grand Conjunction of all 5 visible planets in 1059 BC formed a <text> that the Zhou subjects of the Shang interpreted as the shift of political legitimacy licensing them to prepare to overthrow the Shang royal house. Pankenier illustrates how the entire, puzzling Shiji account of the ultimate conquest of the Shang by King Wu of the Zhou can be unpacked in terms of observations of the motion of the planets against a

stellar field interpreted as a geographical analogue to China, an astrological template well attested from the Warring States era on. Pankenier further demonstrates how the dates that the Zhushu jinian gives for the founding of the Shang suggest that a similarly extraordinary, though somewhat different, planetary conjunction, occurring in 1576 BC, was the impetus for Cheng Tang’s overthrow of the Xia Dynasty. If Pankenier is correct, few aspects of religious ideology could be considered more central to state religion in the Shang than these astronomical issues.”

“Pankenier notes that Grand Conjunctions occur at intervals of approximately five centuries, and are thus, for cultures observant of the sky, likely to be associated with portentous events.”

“Bronze was the most advanced and costly technology of the time, and the Shang chose to invest a very high proportion of its most precious natural and human resources in this ritual industry, in service to the dead, who were nourished from these vessels.”

“Robert Bagley, building on the theories of Max Loehr, argues strongly that the animal motifs on Shang bronzes evolved from purely artistic imperatives, and that they carry no specific religious significance (Shang ritual bronzes in the Arthur M. Sackler collection [Cambridge, Mass., 1987], pp. 21–22). The success of Loehr’s analysis of stylistic evolution in predicting the dates of excavated vessels, and its function in discouraging literal correspondences between imagery and myth, command respect. However, I do not think that it is necessary to reason from the cogency of stylistic evolution that religious factors must be excluded.”

Kwang-Chih Chang – Art, myth, and ritual: the path to political authority in ancient China (Cambridge, Mass., 1983)

“Ken’ichi Takashima suggests that diviners understood oracle bones to be inhabited by a supernatural force, min: <the numen of the bone,> that rendered them efficacious and whose action was detectable to diviners and the king, as recorded in the king’s prognostications or diviner marginalia (<Towards a more rigorous methodology of deciphering oracle-bone inscriptions>)”

“See also Victor Mair’s argument that wu of the late 2nd millennium BC represented an Indo-European presence in China, and should be understood in terms of practices associated with magi (<Old Sinitic ∗myag,

Old Persian maguš, and English ‘magician,>Early China15 [1990], pp. 27–

47).”

Wu Hung – Monumentality in early Chinese art and architecture (Stanford, 1995)

Robert Eno – The Confucian creation of Heaven: philosophy and the defense of ritual mastery, 1990

“Space does not permit a more detailed analysis of the role of dance in the oracle text corpus, and the degree to which oracle texts may support the validity of Childs-Johnson’s theory of the relation of mask dance to animal imagery and, perhaps, to the way in which the Shang conceptualized and encountered members of the pantheon in a performance context, remains to be tested.”

“Cracking [with the boys!] on guisi day (the day of) performance of an yi-rite at the shrine of Wenwu Di-yi; divining about whether the king, by performing a shao-sacrifice to Cheng Tang by means of an exorcism by cauldron using two female captive victims, and libation of the blood of three rams and three pigs, will in this way be correct.”

“While the Shang lineage and temple systems were ordered according to the cyclical-stem [ciclo da árvore genealógica] system, which organized both the ancestral pantheon by temple designation and the sacrificial schedule by corresponding day, the Zhou organized their lineages according to a system of alternating generations known as zhao-mu.” “We occasionally find the familiar figure of Di, but the term seems to be fused with the new high Power, Tian, who is mentioned with considerable frequency. Former Lords and Nature Powers have disappeared.”

“(on problems with dating, see Edward L. Shaughnessy, Sources of Western Zhou history: inscribed bronze vessels [Berkeley, 1991], p. 242, n. 51).”

“But we need to bear in mind that Zhou bronze inscriptions are not comparable to the oracle texts. They are not religious divinations; their primary purpose is to commemorate political and personal events leading to some reward for the vessel owner. They are not state documents; the men who commissioned these texts were members of a disparate elite class. Most had no lineage ties to the royal Ji lineage of the Zhou, and many seem to have been far removed from state power, both in rank and in geographical proximity. Ultimately, comparison of Shang and Zhou pantheons on the basis of recovered contemporary textual sources is simply not currently a feasible project.”

“Tian has taken on the role of ethical guardian, rewarding and punishing rulers according to the quality of their stewardship of the state. The relationship of the ruler to the High Power has now added to worship the fulfillment of an imperative to govern according to moral standards.”

“On the stability of the early Western Zhou, see Shaughnessy, <Western Zhou history,> Cambridge history, p. 318.” “On the fengjian system, see Hsu and Linduff, Western Chou civilization, 147–85. On the term fengjian as distinct from <feudalism,> see Li Feng, <Feudalism and Western Zhou China: an analytical criticism,> Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 63.1 (2003), pp. 115–44. The geopolitical dynamics of Zhou state building is elucidated with great clarity in Li Feng, Landscape and power in early China: the crisis and fall of the Western Zhou, 1045–771 B.C. (Cambridge, Eng., 2006).”

“Conclusion

The Confucian Analectsteaches us that knowledge is clarity about what things you know and what things you don’t, and in the case of Shang state religion, this is a difficult distinction to sustain. Based on the traditional narrative of history, we can understand the Shang as ancestral to later eras of Chinese culture and bring those expectations to our primary body of recovered contemporary data, the late Shang oracle texts. But archaeology has complicated our understanding of the cultural milieu surrounding the Shang state, and of the nature of that state itself, and this calls for increasing caution when interpreting Shang evidence in terms of cultural features typical of subsequent eras.”

SHANG AND ZHOU FUNERAL PRACTICES

∗

ALAIN THOTE (Trad. Margareth McIntosh)

Further readings:

Colin Renfrew, Archaeology: theories, methods and practice (London, 1991).

Ian Morris, Death-ritual and social structure in classical antiquity (Cambridge, 1992).

Alain Testart, La servitude volontaire: essai sur le rôle des fidélités personnelles dans la genèse du pouvoir, 2 vols (Paris, 2004).

“Generally, the practices associated with death are interpreted in terms of social rank, prestige or wealth, rather than from a religious point of view. (…) Also, if the rites associated with death include gestures, words, songs and various material manifestations and, as such, form an essential part of the religion of the times, the archaeological approach has only the data from the material culture to go on, that is, the arrangement and content of isolated tombs and cemeteries. With these reservations, in the case of ancient China the data gathered during the excavations are exceptionally rich. They show that during the Bronze Age (about 1500–300 BC) the shape and content of the tombs show significant continuity. At the same time, certain periods were marked by great changes, even discontinuities in the transmission of burial practices. It is these periods which will retain our attention because, through the archaeological data, it is in them that the relation which men have entertained with death is more clearly evident.”

“Another example of the continuity of funeral customs, as the practice was carried on till the beginning of the empire, is a small object placed in the dead person’s mouth in two tombs at Fuquanshan. One of them was in carnelian, the other in jade. The vessels, which probably contained food offerings, were placed at the head and foot of the deceased. Near the dead person or on his body were found jade axe blades, some of which were hafted at the moment of burial. Their presence may be interpreted in various ways, all non exclusive. The weapons symbolized without any doubt the deceased’s status as warrior, as later on in the Bronze Age. They also materialized the prestige of a man capable of concentrating in his hands considerable wealth. Objects in jade, a material difficult to carve, require an exceptionally long time to make, and therefore indicate marked social inequalities characterizing a highly hierarchical organization. The idea the weapons served to protect the corpse, in a real or symbolic way, may also be envisaged. But in this case, what was the purpose of the protection? Was it against evil spirits?” “Jade did represent the noblest material and was therefore used for body ornaments and prestige (or symbolic) weapons, as well as for the ritual objects that accompanied the dead (bi disks, cong cylinders).” “When their original disposition has not been disturbed, they are still found in the places no doubt then considered as vital as, in the tombs of Chu royal members of the 4th century BC, at the top of the skull, all along the head and the hips, on his or her sexual organ, and on the feet.”

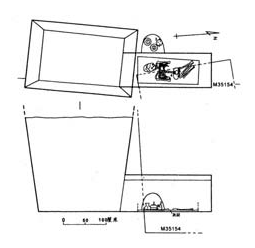

“Oriented north-south, give or take a few degrees, the pits were square or rectangular and provided with two opposing ramps or, for the largest, with four sloping ramps producing a cruciform complex.” “The length of tomb 1217 was about 120 meters from its northern to southern end, while the more <modest> tomb at Wuguancun had a total length of about 45 meters. The shaft, about ten meters deep, had nearly vertical walls pierced by the ramps. Not all the ramps go all the way down to the bottom level of the shaft, as their first function was probably to perform the rites which preceded the closing of the tomb.”

“Other victims were executed while the pit and access ramps were filled in, and then around the tomb as well. In the single royal necropolis of Anyang there were more than one thousand sacrificial pits and additional burials outside the main tombs. The sacrifices were made either during the funeral or at regular intervals after the closing of the tomb. With all these sacrificial pits and burials, death was present all around the votive temple and the royal tomb.”

“If we compare the position of the humans sacrificed on the roof of the outer coffin with the ritual bronzes inside this coffin, we see that the human victims are concentrated directly above the bronzes.”

“Cinnabar has a bright red color and may be associated with the sacred. In the Shang period, it was not yet a medicine for immortality as it would be during the Han period.”

“109 ritual bronzes were inscribed with the name of Fu Hao and therefore cast in her lifetime, whereas several other vessels were given to her at the time of her death. The furnishings comprised personal goods accumulated, or rather collected, during the deceased’s life and, no doubt, objects offered at the time of the funeral.”

“The social pyramid

Members of the society at all levels seem to have been involved in the funerals of their leaders, particularly their king. The investment in time, labor and material goods for the building of the tombs and the supply of their furnishings is simply not quantifiable. For a single royal tomb, thousands of foremen, specialized craftsmen, workers, and slaves were mobilized for years. Moreover, as the Shang community was patrilinear, the difference in the treatment of kings and their wives was considerable. It can be measured in the size and form of the tomb, in the wealth of its furnishings, and in the number of human victims who accompanied the deceased. Although a queen such as Fu Hao enjoyed great prestige, the luxury of her tomb, one of the wealthiest of Chinese antiquity, is nothing in comparison to the tomb of a king.”

“The records in the oracle inscriptions concerning Fu Hao’s life and deeds are testimony to her role as a general of the armies involved in campaigns against countries that the Shang considered their dependencies but had rebelled against their master. She is also known for possibly having given birth to one king of the succeeding generation. See Robert L. Thorp, China in the early Bronze Age: Shang civilization (Philadelphia, 2005), p. 137.”

“Vessels for a kind of beer dominated in the Shang period: according to type, they served to store the beverage (hu, pou, you, lei, fou), to pour it (gong or he, ladles [concha de sopa]), perhaps to heat it, or to drink it (jia, jue, gu).” “In fact, it is difficult to separate the pourers by their form, since some of them were used to hold water for ablutions and others to dilute water with beverages. In the same way, the exact function of each container is not always clear.”

“They were often placed pell-mell [aleatoriamente] in the same pit, without any grave goods; sometimes their skeletons were found incomplete. They were propitiatory victims, chosen among the prisoners of war according to Shang oracle bone inscriptions, and doubtless also from among persons at the bottom of the social pyramid. Human offerings to the deceased were in no way different from the offerings of animals (birds, elephants, dogs, etc.), also sacrificed by hundreds throughout the royal necropolis.”

“Possibly, like the owners of the sacrificial burials surrounding the main tomb the persons of the second category followed their master of their own free will, with the promise of a life in the next world similar to the one they enjoyed on earth and out of fidelity. They are not offerings in the proper sense, because these people have not been <offered> by one person to another (or to a god). There was neither change of owner nor conveyance of one person to another. The word <sacrifice> to qualify the act that enabled the individuals to accompany in death the person whom they served is no doubt inappropriate. Thus here in death the social relations which had existed in life between the tomb’s owner and his personnel were perpetuated for eternity.”

“In particular, as of writing, no Zhou [dinastia sucedânea da Shang] royal tomb has been discovered, and this limitation probably influences our analysis of the tombs of this period.”

“the rulers’ tombs seem to have had comparable proportions from one principality to another, as if standards were followed by these lords, or else were imposed on them.”

Lothar von Falkenhausen – Chinese society in the age of Confucius (1000–250 BC): the archaeological evidence (Los Angeles, 2006)

“These ramps and also the area situated above the guo contained several wheels of dismantled chariots, and even one whole chariot. In many cases, near the tombs there were pits containing sacrificed horses and chariots and, occasionally, the charioteer. The horses were killed in two ways: either a large number was buried alive (up to 45 horses), or they were killed before being carefully put in the pits.”

“if the head is turned toward the north, it is to let the soul go to the dwelling of the dead.”

“Lacking raw material, the artisans did not hesitate to carve the plaques again independently of their previous decoration, for the presence of jade inside the coffin was considered essential for prophylactic reasons.”

“The repetition of similar vessels gives these sets a far more imposing aspect, allowing immediate evaluation of the wealth and status of a prince. According to Jessica Rawson, these changes indicate innovations in the ceremonies held in front of gatherings that were more numerous than before. Finally, sets of bells and musical stones are included, and these pieces are also subject to variation in accord with the social position of their owner.”

“Several vessels bear inscriptions, but they make up only a very small part of the sets of bronzes, no doubt less than 1 percent. (…) One formula appears frequently, either in isolation or to conclude a text: <May my sons and the sons of my sons (all my descendants) forever preserve these vessels

and use them eternally (for worship).”

“the vessels deposited in the tombs are often the same ones (and in many cases part of) the deceased used in his own lifetime to sacrifice to his dead father and to his ancestors, and thus to communicate with them.”

“In 771, following a revolt which ended with the assassination of the king, the court had to leave hurriedly the capital near modern-day Xi’an (Shaanxi) to take refuge in the secondary capital located near Luoyang (Henan). Royal power, greatly weakened by these events, was never again able to control the princes who had previously been (almost) completely subordinate to the king. Archaeological evidence reveals the growing independence of the lords in two converging ways. In the evolution of burial customs, changes, slow at first, became manifest during the course of the 6th century BC. Burials in the principalities then offered the elites an occasion to display their power, at times in an extravagant way.”

“This tomb has two ramps, of a total length of around 280 meters. It contained 166 human victims, both accompaniers and sacrificial victims. The first were put in coffins of different types of wood, placed more or less near the prince, probably according to the place they occupied in his suite during their lifetime, while the others were buried without a coffin. The tomb was 24 meters in depth. Composed of compartments with communicating doors in the fashion of a dwelling for the living, the guo is complex. This is the first evidence of such an internal organization, but as the tomb has been robbed several times, we cannot know if the distribution of the furnishings between the compartments followed an arrangement which already suggested a dwelling.”

“Some of them, on the model known as <catacomb-tomb,> were composed of shafts whose bottom was dug out laterally so as to form a chamber closed by a low wall of unfired adobe bricks, wood or branches. The body of the deceased rested inside with burial objects, deposited at his head in most cases. The custom of burying a dog in a waist pit under the coffin of the deceased has been attested in Qin, as in several other sites of the same period in north China. The prevailing orientation for the deceased’s head is the west.”

“Many of the dead are lying on their backs, legs folded to the left or right side. This is a specific characteristic of a large number of Qin burials, a fact that is explained in various ways. Whatever the reason, this is a cultural marker related to very ancient practices widespread in Qinghai and Gansu and, farther afield, in central Asia. This custom continued until the late 3rd century, as exemplified in tomb 11 at Shuihudi, Yunmeng county, Hubei, dated to 217BC. It may be linked to religious beliefs. A folded leg posture could frighten away evil spirits according to an almanac discovered at Shuihudi.”

Falkenhausen – Mortuary behavior

“As for the earthenware vessels imitating ritual bronze vessels, they developed in the Chu area in larger proportions than in any other place, and earlier, from the 8th century BC on. The production of pots specifically for burial and fired at a lower temperature so that they were unusable in daily life appeared much earlier in China, but they did not occur in such numbers as in the Chu kingdom and the Qin principality during the Eastern Zhou period. Also, the imitations of bronze vessels in Chu are often of high quality. By contrast, the relatively low quality of the burial objects is a characteristic trait of the Qin. The ritual bronze vessels, like the ritual jades found in Qin tombs are among the less well worked of the Zhou period, made in an awkward style. Several of the elements just mentioned seem to indicate that Qin people tended to reserve for the dead objects necessarily different from those of the living, either cheap substitutes or models of real objects.”

“Of vast dimensions (around 140 square meters), the guo was composed of 4 compartments (large enough to be considered as chambers, which is not generally the case elsewhere in the Chu kingdom) arranged in an irregular layout: to the east, the chamber where the deceased reposed, in two nested coffins; in the center, a chamber containing the ritual vessels and a set of musical instruments used during the ceremonies; to the west, a chamber holding the coffins of 13 women; to the north, a small chamber containing weapons, two enormous bronze jars, and the inventories of the chariots which composed the cortege and carried the gifts of the relatives of the deceased and princes and officers close to him at the time of the funeral. (…) 8 coffins containing the remains of young women, no doubt servants or musicians, and, finally, a dog’s coffin placed close to that of the deceased (in earlier tombs, dogs were found buried in sacrificial pits). On a symbolic level, this chamber seems to have represented his private apartments, whereas the central chamber was used for rituals and symbolized his official life. The northern chamber formed a kind of armory, with everything necessary for a warlord of this period. The western chamber probably contained the household staff of the deceased (perhaps in charge of the ritual ensemble or the musical instruments of the central chamber). The 4 rooms communicated with each other, at least symbolically, because the openings were very small (about 40cm wide and high). The idea of communication within the tomb is also suggested by the paintings on the double coffin, since on the sides of the inner coffin a window and two doors were represented, and the larger coffin had on one side a small opening of the same size as the openings between the chambers.”

“The idea that a man had two souls hun and po seems to have appeared in the 4th century BC or even before.”

“For the location of cemeteries or isolated tombs, the Chu people chose a hill or a terrace, an elevated area, as opposed to the plain, often swampy and reserved for crops. Besides these practical reasons, there were perhaps other reasons, religious or symbolic, for the phenomenon is characteristic of the entire Chu cultural area. The tombs are characterized by the presence of an outer coffin of limited dimensions (around 9m × 7m for the largest), carefully constructed with thick and solid beams.”

“The number of compartments, between one and six, is proportional to the size of the tomb, and seems to be related to the status of the deceased, as is his coffin, which may be contained in one or two other nested coffins placed in the central compartment of the guo.”

“In the largest Chu tombs, the orientation to the east prevails, whereas most of the deceased of medium-sized and small tombs were oriented to the south.”

“In effect, we see the decline of the ritual bronzes in two different ways. On the one hand, in the 4th century BC in Chu, not only do they no longer carry inscriptions, they are often badly cast, not smoothed after the cast, even unusable. On the other hand, the use of earthenware replicas of ritual vessels increased greatly in the Chu kingdom (this phenomenon existed also in the other kingdoms and principalities, but in lesser proportions). While the ritual ensembles no longer played their previous leading role among the burial objects, new and different categories of objects, related to earthly life, were present in the tomb: furniture (beds, low tables, arm and back rests, lamps, gaming tables), luxurious tableware (separate from the ritual utensils), personal effects (combs, hairpieces, hairpins, mirrors, fans, shoes, clothes), sets of writing utensils, bamboo slips, and always, following a centuries-old custom, weapons. In the choice of objects various functions appear: the conduct of war, grooming [assepsia e adorno], entertainment, the pleasures of the table, rites which the deceased should follow during his lifetime. While the ritual sets composed of substitutes of low quality are only symbolically present, the other objects are of ostentatious luxury.”

“In the arrangement of the tomb, as in its contents, the material comfort of the deceased was thereafter assured. Beyond the conformism inherent in the social classes to which the deceased belonged, the choices made for the composition of the burial furnishings seem to be in accordance with the personal destiny of the deceased, and not only with the social position he occupied in his lifetime.”

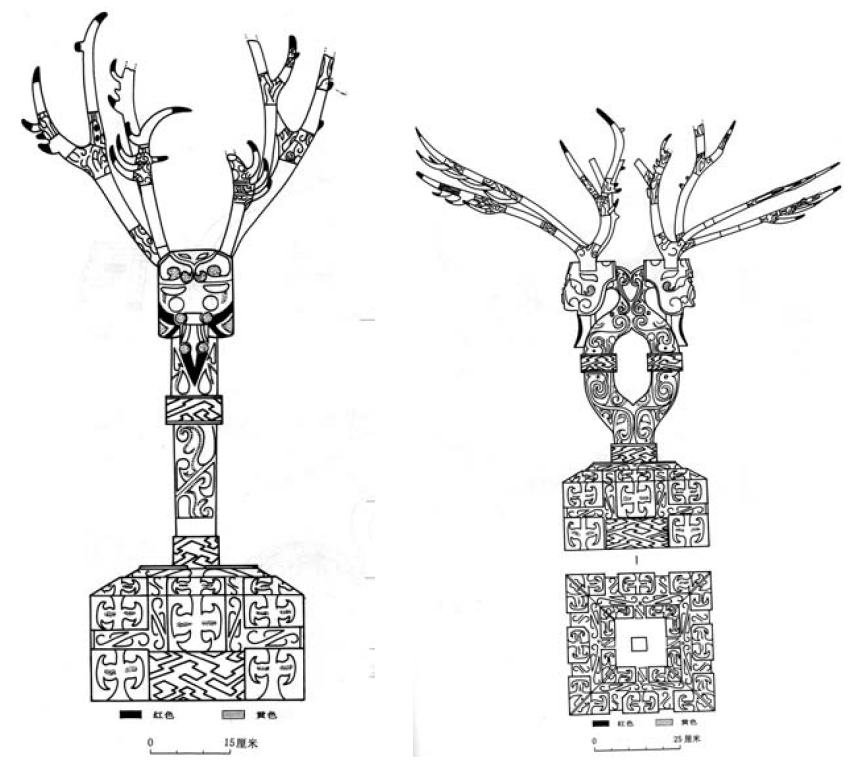

“At the same time, the protection of the tomb aimed for efficacy, and the measures of a magical character were no longer expressed by animal or human sacrifice but by the presence of sculptures of monster guardians of the tombs, the zhenmushou [representadas abaixo], whose function was to ward off the serpents which would come and feed off the corpse. Perhaps the living sought also in this way to protect themselves from the dead, to dissuade them from coming back to torment the living.”

BRONZE INSCRIPTIONS, THE SHIJING AND THE SHANGSHU:

THE EVOLUTION OF THE ANCESTRAL SACRIFICE DURING THE WESTERN ZHOU

∗

MARTIN KERN

“even the earliest texts reflect linguistic and intellectual developments that, when compared to the data available from bronze inscriptions, postdate the early Western Zhou reigns. Thus, these texts were either partially updated or wholly created not by the sage rulers of the early Western Zhou but by their distant, late-Western or early Eastern Zhou descendants who commemorated them. In the case of the Documents, this is true not only for those speeches that have long been recognized as postdating the Western Zhou—for example, King Wu’s (1049/45–1043 BC) <Exhortation at Mu> (Mu shi), purportedly delivered at dawn before the decisive battle against the Shang, but clearly a post-Western Zhou text—but also for the 12 speeches that have been generally accepted as the core Documents chapters from the reign of King Cheng (1042/35–1006 BC), including the regency of the Duke of Zhou (1042–1036 BC)¹. In other words, all our transmitted sources that speak about the early Western Zhou are likely later idealizations that arose in times of dynastic decline and from a pronounced sense of loss and deficiency: first in the middle and later stages of the Western Zhou, that is, after King Zhao’s (r. 977/75–957 BC) disastrous campaign south; and second in the time of Confucius (551–479 BC) and the following half millennium of the Warring States and the early imperial period.

¹ The argument for the authenticity of these speeches is outlined in Herlee G. Creel, The origins of statecraft in China, vol. 1, The Western Chou empire (Chicago, 1970), pp. 447–63, and re-iterated in Shaughnessy, <Shang shu (Shu ching),> in Early Chinese texts, ed. Michael Loewe (Berkeley, 1993), p. 379. However, Kai Vogelsang, <Inscriptions and proclamations: on the authenticity of the ‘gao’ chapters in the Book of documents,> Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 74 (2002), pp. 138–209, has raised serious doubts about Creel’s conclusions; instead, his sophisticated and detailed study (and recent works by others cited there, including by He Dingsheng and Vassilij M. Kryukov) suggests a late Western Zhou or early Chunqiu date for the early layers of both the Songs and the Documents. A similar argument is advanced in Kern [eu mesmo], <The performance of writing in Western Zhou China,> in The poetics of grammar and the metaphysics of sound and sign, eds. Sergio La Porta and David Shulman (Leiden, 2007), pp. 109–76.”

Baxter, “Zhou and Han phonology in the Shijing,” in Studies in the historical phonology of Asian languages, eds. William G. Boltz and Michael C. Shapiro (Amsterdam, 1991)

“In general, the case of the speeches is more problematic than that of the hymns. While the Songs were largely stable in their archaic wording since at least the late 4th century BC, regardless of their high degree of graphic variants in early manuscripts and profound differences in interpretation¹, the text of the Documents was still much in flux far into Han times. However, despite these editorial interventions, the early layers of the received Songs and Documents display an archaic diction in lexical choices and ideology that in general fits well with the epigraphic evidence from late (but not early) Western Zhou and early Springs and Autumns (Chunqiu) period (722–486 BC) bronze inscriptions.

¹ Because of the basic monosyllabic nature of the classical Chinese language and its large numbers of homophones, this is not to say that those who in the early period occasionally wrote down parts of the Songs necessarily agreed in every case on the word behind the many different graphs that could be used to write it (…) see Kern, <Excavated manuscripts and their Socratic pleasures: newly discovered challenges in reading the ‘Airs of the States,’> Études Asiatiques/Asiatische Studien 61.3 (2007), 775–93. However, textual ambiguity was a far more serious problem with the <Airs of the States> (Guofeng) section of the Songs than with the ritual hymns related to the ancestral sacrifice.”

“Untouched by later editorial change, the bronze texts provide not only the best linguistic, historical and ideological standards against which the Songs and the Documents have to be measured and dated; they also provide pristine contemporaneous evidence for the Western Zhou ancestral sacrifice itself. While their information about specific ritual procedures is not nearly as detailed as in the hymns and speeches (to say nothing of the much later elaborations in the ritual classics and other texts), they nevertheless open a window into some very specific evidence of court ceremony, present us with the very artifacts that were used for sacrificial offerings, and allow us to chronologically stratify important historical developments in Western Zhou ritual practice and ideology between the early (ca. 1045–957 BC), middle (956–858 BC) and late (857–771 BC) periods of the dynasty. Especially the last point is critically important, as it helps us to rethink some of the central tenets of Western Zhou religion. To raise some specific examples, none of them trivial: in the early hymns and speeches from the Songs and the Documents—and far more so in later sources—the interrelated notions of <Son of Heaven> (tianzi) and <Mandate of Heaven> (tianming) appear as singularly central and critical to the political legitimacy and religious underpinnings of early Western Zhou rule. Neither term, however, appears with any frequency in early Western Zhou bronze inscriptions, that is, during the reigns of kings Wu, Cheng, Kang (1005/3–978 BC), and Zhao.”

“The commemoration of origin, and with it of the religious legitimacy of the entire dynasty, created an ideal past as a parallel reality to an actual experience of loss and decay. When Confucius and his followers began to enshrine the ideal past in an ideal body of texts—later called the Five Classics(Wu jing), with the Songs and the Documents at its historical core—they unknowingly preserved not the cultural, political and religious expression of the early Western Zhou but only its subsequent, and already highly idealized, commemoration.”

“I disagree with Maspero (and Shaughnessy) on the—to my mind anachronistic—idea of individual literary authors or even a <solitary poet> (Shaughnessy) at the Western Zhou royal court; instead, I see the hymns, speeches and inscriptions as the work of ritual specialists who composed these texts in an institutional framework.”

“Western Zhou bronze inscriptions mentioning military affairs record only victories; and while the famous Shi Qiang-pan inscription of ca. 900 BC praises King Zhao for having subdued the southern people of Chu and Jing, other historical sources inform us that the royal expedition south suffered a crushing defeat that destroyed the Zhou army and even left the king dead. The fact that a royal scribe of highest rank was granted a wide and shallow water basin inscribed with a text that was as prominently displayed as it was historically inaccurate merely two generations after King Zhao’s death shows that the true question answered by the inscribed narrative was not, <What has happened?> but, <What do we wish to remember?> (…) In both hymns and speeches, this perspective is consistently emphasized through the intense use of first and second person pronouns.”

“by its nature of <multi-media happenings> that involved converging patterns of song, music, dance, fragrance, speech, material artifacts and sacrificial offerings, the sacrifice embodied the cultural practices of elite life” “And finally, the ancestral sacrifice was directly connected to other ritual, social and political activities, among them banquets and ceremonies of administrative appointment. In these combined functions, the ancestral sacrifice was at the very center of Western Zhou social, religious and political activities.”

Falkenhausen, Ritual music in Bronze Age China: an archaeological perspective (PhD diss., Harvard University, 1988)

“the role of the impersonator (shi), in which an adolescent member of the family served as the medium for the ancestral spirits”

“<may sons of sons, grandsons of grandsons, forever treasure and use [this sacrificial vessel]>Xu Zhongshu, <Jinwen guci shili>, Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology 6.1 (1936), 1–44, has estimated that 70–80% of all bronze inscriptions end with this formula.”

“While circumstantial evidence strongly suggests the presence of writing in administrative, economic, legal and other pragmatic contexts, this writing was not preserved in the ways the inscriptions (through durable material) and the hymns and speeches (through tradition) were. Phrased the other way around, without the institution of the ancestral sacrifice, none of the earliest sources would have come into existence or have been transmitted the way they were.”

“Warring States and early imperial texts contain elaborate descriptions of the temple and refer to it primarily as miao (temple) or zongmiao (lineage temple); the three ritual classics in particular provide extensive information about its multi-layered architecture in conjunction with the rituals performed within it.”