“Noam Chomsky has been generous in expressing his disagreements in private communication (an exchange of views is included in my earlier book, Extraterritorial: Papers on Literature and the Language Revolution).”

“Ningún problema tan consustancial con las letras y con su modesto misterio como el que propone una traducción.”

J.L. BORGES, Las versiones Homéricas, Discusión, 1957

“La théorie de Ia traduction n’est donc pas une linguistique appliquée. Elle est un champ nouveau dans Ia théorie et Ia pratique de Ia littérature. Son importance épistémologique consiste dans sa contribution à une pratique théorique de l’homogénéité entre signifiant et signifié propre a cette pratique sociale qu’est l’écriture.”

HENRI MESCHONNIC, Pour la poétique II, 1973

I. UNDERSTANDING AS TRANSLATION

Shakespeare, Cymbeline, Ato II

“Is there no way for man to be, but women

Must be half-workers? We are all bastards”

“Não poderia prosseguir a espécie humana sem

a cópula? Por que há de participar a mulher?”

REMÉDIO SECULAR

O chifre tem propriedades terapêuticas. Pois não é que cada cabra macho já nasce com o remédio de seus males autocriado(s)?

Corta teu chifre, queima-o e espalha as cinzas

Para se vingar…

Do chifre e do remédio.

“O vengeance, vengeance!

Me of my lawful pleasure she restrain’d(*),

And pray’d me oft forbearance: did it with

A pudency so rosy, the sweet view on’t(*)

Might well have warm’d old Saturn(*); that I thought her

As chaste as unsunn’d snow(*). O, all the devils!

This yellow Iachimo, in an hour, was’t not?

Or less; at first? Perchance he spoke not, but

Like a full-acorn’d boar, a German one,

Cried <O!> and mounted; found no opposition

But what he look’d for should oppose and she

Should from encounter guard. Could I find out

That woman’s part in me–for there’s no motion

That tends to vice in man, but I affirm

It is the woman’s part: be it lying, note it,

The woman’s: flattering, hers; deceiving, hers:

Lust, and rank thoughts, hers, hers: revenges, hers:

Ambitions, coverings, change of prides, disdain,

Nice longing, slanders, mutability;

All faults that name, nay, that hell knows, why, hers

In part, or all: but rather all. For even to vice

They are not constant, but are changing still;

One vice, but of a minute old, for one

Not half so old as that. I’ll write against them,

Detest them, curse them: yet ‘tis greater skill

In a true hate, to pray they have their will:

The very devils cannot plague them better.”

“Ah, vingança, vingança!

Do meu direito natural ela me desposou,

E rogou ilimitadas vezes: Tem misericórdia,

Com uma pudicícia tão rósea-roseta,

Um olhar tão doce inocente

Que derreteria até o velho Tempo;

Até pensei nela casta como

neve tapada. Ah, pelos Diabos!

Juan O Íntegro, esse galinha, num instante

No primeiro encontro? Talvez tenha-

Lhe metido sem sequer trocarem cumprimentos

Como com um leitão alemão,

Montou em cima com um grito;

E a montaria não se rebelou,

E como foi que a porta ele arrombou

do celeiro? poderia eu entender o que se passa

na cabeça da mulher? — porque de homem se tratando

não há o que nos force a comer do fruto proibido,

a não ser uma Eva em nossas vidas, aquela

campeã na arte de mentir na horizontal;

bajular, enganar; ceder à luxúria, cobiçar,

coisa de mulher: ah, e se vingar;

Ambições, dissimulações, véus de orgulho e desdém,

Paciência para esperar o momento de pecar;

escândalo, volubilidade;

Todos os pecados que, só deus sabe, só recaem,

Ou maior parte, nelas: Porque nem no vício

São elas tão constantes, mas é tudo imprevisível;

Um vício, um capricho de um minuto,

logo é trocado, por um bem mais no-viço.

Deteste-as, amaldiçoe-as: qu’importa! se elas são

especialistas nesse tipo de rancor,

sempre se acham com a razão:

nem demônios praguejam como elas!”

COMENTÁRIOS DOS (*)

“Lawful pleasure” pode ter ou não uma conotação sexual. Mas decerto é patriarcal – e não seria menoscabar o problema tratá-la como “mera questão jurídica”?

Pudicícia, rosada, doce… Todo o sintagma é carnal, erótico… Uma rosa, um botão de rosa, é tão inocente… Até ser deflorado… A virgem é pueril, não mente, até enrubescer, e o que seria a rosa que não é pálida? Talvez alguém que se envergonha de si própria, que se percebe, finalmente, complexa, mentirosa… A mesma cor da paixão e do imprevisível. “Roseta” lembra buceta, quem vê cara não vê genital… Pau-dora, origem do mal. A etimologia da palavra não engana os portugueses, só os lúbricos brasucas… Pau-pra-toda-obra. Doce pode ser gosto ou cheiro, para o heterossexual a buceta emana olores eflúvios e é apetitosa, quanto mais inutilizada ela é. A pudica na verdade é uma piranha (inconsciente), é isso que William na boca de Póstumo (nome sugestivo) quer dizer.

O irônico é que se eu estivesse a ver coisas (safadeza) em cada versostrofe, Shakespeare não mexeria (shake) com o leitor e seus sentimentos com tanta freqüência, sem respiro: Zeus, o mulherengo do Olimpo, que destronou o Pai-Tempo, que era outro mulherengo, todos eles vira-e-mexe sacaneados por mulheres… A que vem essa citação aqui? Warm é tão ambíguo quanto o róseo, pode ser enternecer, amolecer, como justamente o oposto excitar, entesar. O fato é que a mulher quebra o deus, preferi o derreter. Curva-o, com suas curvas, e aquele olhar. E olha que ele é o próprio Cronos, que anda com o ponteiro, e já viu de tudo nesse mundéu… Que sensação cruel.

Já que ela é inocente, posso dizer que é uma tapada. Uma neve tapada, recoberta, sem acesso ao Sol (deus Apolo, um pouco de razão na vida de Zeus, digo, do Pai mulherengo). Mas só assim para ser fria e glacial, impiedosa na hora de machucar… De novo aquilo da neve branquinha. A rosácea não!

Iachimo é Giacomo, o James bíblico. Também significa “complementador”, “reparador”, daí o epíteto “íntegro”. Porém, como nesta estória ele vem para galantear a mulher dos outros, é Juan e não James! Amarelo quer dizer literalmente “galinha” em Inglês.

Quanto aos outros quatro quintos, foram muito mais fáceis; se não é Eva o protótipo de tudo o que Póstumo falou, mato-me eu!

* * *

O poder do editor é de Thor!

“I am quoting from the Arden edition of the play by J.M. Nasworthy. His version of Posthumus’s speech embodies a sum of personal judgement, textual probability, and scholarly and editorial precedent. It is a recension which seeks to gauge the needs and resources of the educated general reader of the mid-twentieth century. It differs from the Folio in punctuation, line-divisions, spelling, and capitalization. The visual effect is markedly different from that achieved in 1623.” “A first step would deal with the meaning of salient words – with what that meaning may have been in 1611, the probable date of the play. Already this is a difficult step, because current meaning may not have been, or have been only in part, Shakespeare’s. In short how many of Shakespeare’s contemporaries fully understood his text? An individual and a historical context are both germane [pertinentes].”

“One might begin with the expressive grouping of stamp’d, coiner, tools, and counterfeit. Several currents of meaning and implication are interwoven. They invoke the sexual and the monetary and the strong, often subterranean links between these two areas of human will.” “The meshing of adulteration with adultery would be characteristic of Shakespeare’s total responsiveness to the field of relevant force and intimation in which words conduct their complex lives.”

Seu destino está selado, e ele é uma carta prestes a ser entregue.

“the O.E.D. and Shakespeare glossaries here direct us to Much Ado About Nothing. It soon becomes evident that Claudio’s damnation of women in Act IV, Scene I foreshadows the rage of Posthumus.”

“Pudency is so unusual [?] a word that the O.E.D. gives Cymbeline as authority for its undoubted general meaning: <susceptibility to shame>. A <rosy pudency> is one that blushes; but the erotic associations are insistent and part of a certain strain of febrile bawdy [obscenidade] in this play.” Eu não disse?

“Shakespeare uses chaste three lines later with the striking image of unsunn’d snow. This touch of unrelenting cold may have been poised in his mind once reference was made to old Saturn, god of sterile winter.” Dessa eu não sabia: Saturno, Deus dos Anéis e também do Inverno Estéril! Aquele que carrega a própria morte circular…

“Yellow Iachimo is arresting. The aura of nastiness is distinct.” “Much later, and with American overtones, yellow will come to express both cowardice and mendacity – the <yellow press>.” “Shakespeare at times seems to <hear> inside a word or phrase the history of its future echoes.” [!!!]

– Estou em Constância! – e desligou o telefone o homem, voltando a afundar sua língua nos pêlos pubianos de sua camarada constantina.

“The study of Shakespeare’s grammar is itself a wide field. In the late plays, he seems to develop a syntactic shorthand; the normal sentence structure is under intense dramatic stress. Often argument and feeling crowd ahead of ordinary grammatical connections or subordinations. The effects – Coriolanus is especially rich in examples – are theatrical in the valid sense.”

“He [Póstumo] is quick to anger and to despair. Perhaps we are to detect in his rhetoric a bent towards excess, towards articulation beyond the facts.”

“Posthumus’s philippicis [arenga, diatribe, discurso virulento], at almost every stage, conventional; his vision of corrupt woman is a locus communis. Close parallels to it may be found in Harrington’s translation of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (XVII), in Book X of Paradise Lost, in Marston’s Fawn, and in numerous Jacobean satirists and moralists.” “The nausea of Othello, moving from sexual shock to a vision of universal chaos, and the infirm hysteria of Leontes in The Winter’s Tale have a very different pitch [tom].”

“We know little of internal history, of the changing proceedings of consciousness in a civilization. How do different cultures and historical epochs use language, how do they conventionalize or enact the manifold possible relations between word and object, between stated meaning and literal performance? What were the semantics of an Elizabethan discourse, and what evidence could we cite towards an answer? The distance between <speech signals> and reality in, say, Biblical Hebrew or Japanese court poetry is not the same as in Jacobean English. But can we, with any confidence, chart these vital differences, or are our readings of Posthumus’s invective, however scrupulous our lexical studies and editorial discriminations, bound to remain creative conjecture?” “No aspect of Elizabethan and European culture is formally irrelevant to the complete context of a Shakespearean passage. Explorations of semantic structure very soon raise the problem of infinite series. Wittgenstein asked where, when, and by what rationally established criterion the process of free yet potentially linked and significant association in psychoanalysis could be said to have a stop. An exercise in <total reading> is also potentially unending. We will want to come back to this odd truism. It touches on the nature of language itself, on the absence of any satisfactory or generally accredited answer to the question <what is language?>”

“Indeed at the surface, Jane Austen’s prose is habitually unresistant to close reading; it has a lucid <openness>. Are we not making difficulties for ourselves? I think not, though the generation of obstacles may be one of the elements which keep a <classic> vital.” “No less than Henry James, she uses style to establish and delimit a coherent, powerfully appropriated terrain. What lies outside the code lies outside Jane Austen’s criteria of admissible imaginings or, to be more precise, outside the legitimate bounds of what she regarded as <life in fiction>.” “Entire spheres of human existence – political, social, erotic, subconscious – are absent. At the height of political and industrial revolution, in a decade of formidable philosophic activity, Miss Austen composes novels almost extraterritorial to history. Yet their inference of time and locale is beautifully established. The world of Sense and Sensibility and of Pride and Prejudice is an astute <version of pastoral>, a mid- and late eighteenth-century construct complicated, shifted slightly out of focus by a Regency point of view. No fictional landscape has ever been more strategic, more expressive, in a constant if undeclared mode, of a moral case.”

“the <Chinese box> effect of dependent and conditional phrases make for subtle comedy.”

“Nature, reason, and understanding are terms both of current speech and of the philosophic vocabulary. Their interrelations, implicit throughout the sentence, argue a particular model of personality and right conduct. The concision of Miss Austen’s treatment, its assumption that the <counters> of abstract meaning are understood and shared between herself, her characters, and her readers, have behind them a considerable weight of classic Christian terminology and a current of Lockeian psychology. By 1813 that conjunction is neither self-evident nor universally held. Jane Austen’s refusal to underline what ought to be commonplace, at a time when it no longer is, makes for a covert, but forceful didacticism. <Defects of education>, <inferior society>, and <frivolous pursuits> pose traps of a different order. (…) Only by steeping oneself in Miss Austen’s novels can one gauge the extent of Lucy Steele’s imperfections.” “How much pre-information do we need to parse accurately the notions of simplicity and of interesting character, and to visualize their relationship to Lucy Steele’s beauty?”

“In a usage which the utilitarian and pragmatic vocabularies of Malthus and Ricardo exactly invert, interest can mean <that which excites pathos>, <that which attracts amorous, benevolent sympathies>.”

“A remote sky, prolonged to the sea’s brim:

One rock-point standing buffetted alone,

Vexed at its base with a foul beast unknown,(*)

Hell-spurge of geomaunt and teraphim:¹

A knight, and a winged creature bearing him,

Reared at the rock: a woman fettered there,

Leaning into the hollow with loose hair²

And throat let back and heartsick trail of limb.³

The sky is harsh, and the sea shrewd and salt.

Under his lord, the griffin-horse ramps blind

With rigid wings and tail. The spear’s lithe stem4

Thrills in the roaring of those jaws: behind,

The evil length of body chafes at fault.

She does not hear nor see – she knows of them.”

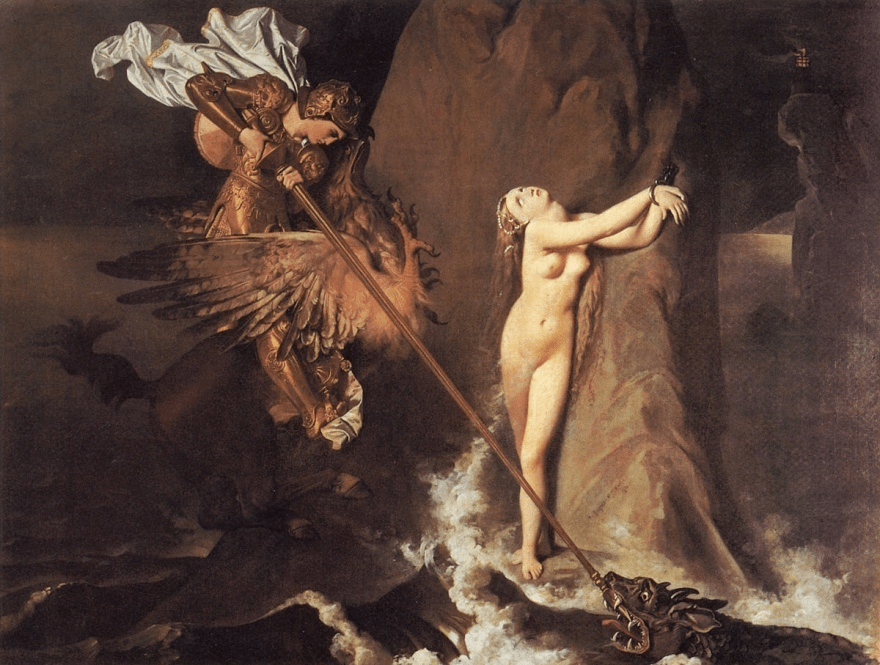

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Angelica Rescued by the Sea-Monster, rendição escrita de um quadro de Ingres (abaixo)

PEQUENO GLOSSÁRIO DE INGRES-ROSSETTI:

brim: horizonte

buffeted: fincada

chafes at fault: dá um coice no vento; é obrigado a recuar

fettered: presa, atada à

foul: horrenda

geomaunt: – (geomante, esclarecido apenas por Steiner – cfr. abaixo)

griffin-horse: cavalo-quimera, grifo

lithe stem: haste flexível

ramp: galopa, cavalga, esvoaça, se aproxima…

shrewd: agitado, maroto

sky is harsh, the: o tempo está feio/fechado

spurge: –

teraphim: ídolo judeu (herético)

“It has a markedly heathen ring and Milton used the word with solemn reprobation in his Prelatical Episcopacy of 1641.”

thrill: vibra

vexed: ameaçada

Linhas especialmente problemáticas assinaladas por números (e sugestões):

“Angélica resgatada pelo Monstro Marinho”

¹ Como se fosse uma entidade do inferno, Cérbero montando guarda //

O brotar da geomancia e dos maus presságios //

O aparecimento de maus augúrios e sinais dos deuses

(essas duas versões grifadas só foram rascunhadas após ler os parágrafos abaixo, que definem o termo arcano geomancy, e geomant, raro na língua.)

² Inclinando-se à beira do abismo, os cabelos ao vento

³ Sem voz e com os pungentes braços ao léu //

Sem poder chamar, mas gesticulando em desespero //

A garganta para trás, os braços desconjuntados

4 Com asas e cauda tensas. A haste da seta, n’entanto, já curva

“Hell-spurge is odd. Applied to a common genus of plants, the word may, figuratively, stand for any kind of <shoot> or <sprout>. One suspects that the present instance resulted from a tonal-visual overlap with surge [uma erupção infernal e caótica, poderia ser a rendição correta].”

“Geomaunt and teraphim make a bizarre pair. The O.E.D. gives Rossetti’s sonnet as reference for <geomant> or <geomaunt>, one skilled in <geomancy>, the art of divining the future by observing terrestrial shapes or the ciphers drawn when handfuls of earth are scattered (geomancy occurs in Büchner’s Wozzeck when the tormented Wozzeck sees a hideous future writ in the shapes of moss and fungi [lama e lodo – o café do reino vegetal]). Rossetti’s source for this occult term may well have been its appearance in Dante:

quando i geomanti lor maggior fortuna

veggiono in oriente, innanzi all’alba,

surger per via che poco le sta bruna . . .

(Purgatorio, XIX. 4-6)

The occurrence of surger so close to geomanti makes it likely that a remembrance of Dante in fact underlies this part of Rossetti’s sonnet and may be more immediate to it than Ingres’ painting.”

Marcadamente, os elementos telúricos do poema rivalizam com a temática marinha do soneto! Outra curiosidade é que o cavaleiro da estória é Roger, que salva a donzela da besta-marinha, mas o título diz o contrário!

MOTIVOS PARA UMA ABSTRAÇÃO

“In a way typical of Pre-Raphaelite verse, the linguistic proposition is validated by another medium (music, painting, textile, the decorative arts). Freed from autonomy, Rossetti’s evocative caption can go through its motions. What do these amount to? No firm doctrine of correspondence is operative: the sonnet makes no attempt to simulate the style and visual planes of the picture. It embodies a momentary ricochet: griffin, armoured paladin, the boiling sea, a swooning figure on a phallic rock [a parte que Freud adoraria] trigger a volley of <poetic> gestures.”

(*) “Indeed, the whole of line 3 foreshadows [prenuncia, remete a] the Pre-Raphaelite strain in Yeats.”

ZEITGEIST DA IGNORÂNCIA

“To our current way of feeling, Rossetti’s poem is a hollow bauble [baboseira vazia]. In short, at this stage in the history of feeling and verbal perception, it is difficult to <read at all> the Sonnets for Pictures.” “We are, in the main, <word-blind> to Pre-Raphaelite and Decadent verse. This blindness results from a major change in habits of sensibility. Our contemporary sense of the poetic, our often unexamined presumptions about valid or spurious uses of figurative speech have developed from a conscious negation of fin de siècle ideals.” “We have for a time disqualified ourselves from reading comprehensively (a word which has in it the root for <understanding>) not only a good deal of Rossetti, but the poetry and prose of Swinburne, William Morris, Aubrey Beardsley, Ernest Dowson, Lionel Johnson, and Richard Le Gallienne. Dowson’s Cynara poem or Arthur Symons’s Javanese Dancers provide what comes near to being a test-case. Even in the cool light of the late 1960s, the intimation of real poetry is undeniable.” “Much more is involved here than a change of fashion, than the acceptance by journalism and the academy of a canon of English poetry chosen by Pound and Eliot. This canon is already being challenged; the primacy of Donne may be over, Browning and Tennyson are visibly in the ascendant. A design of literature which finds little worth commending between Dryden and Hopkins is obviously myopic. But the problem of how to read the Pre-Raphaelites and the poets of the nineties cuts deeper.”

“No tone-values are more difficult to determine than those of a seemingly <neutral> text, of a diction which gives no initial purchase to lexicographer or grammarian.”

“When reading any piece of English prose after about 1800 and most verse, the general reader assumes that the words on the page, with a few <difficult> or whimsical exceptions, mean what they would in his own idiom. In the case of <classics> such as Defoe and Swift that assumption may be extended back to the early eighteenth century. It almost reaches Dryden, but it is, of course, a fiction.”

“We are growing year by year more introspective and self-conscious: the current philosophy leads us to a close, patient and impartial observation and analysis of our mental processes: we more and more say and write what we actually do think and feel, and not what we intend to think or should desire to feel.” Henry Sidgwick, 1869

VERBO & TEMPO

“Language – and this is one of the crucial propositions in certain schools of modern semantics – is the most salient model of Heraclitean flux. It alters at every moment in perceived time. The sum of linguistic events is not only increased but qualified by each new event. If they occur in temporal sequence, no two statements are perfectly identical. Though homologous, they interact. When we think about language, the object of our reflection alters in the process (thus specialized or metalanguages may have considerable influence on the vulgate). In short: so far as we experience and <realize> them in linear progression, time and language are intimately related: they move and the arrow is never in the same place.” “certain cultures speak less than others; some modes of sensibility prize taciturnity and elision, others reward prolixity and semantic ornamentation. Inward discourse has its complex, probably unrecapturable history: both in amount and significant content, the divisions between what we say to ourselves and what we communicate to others have not been the same in all cultures or stages of linguistic development.”

R.B. Lees, The Basis of Glottochronology

“the Indo-European paradigm of singular, dual, plural, which may go back to the beginnings of lndo-European linguistic history, survives to this day in the English usage better of two but best of three or more. Yet the English of King Alfred’s day, most of whose features are chronologically far more recent, is practically unintelligible.”

“The conservatism, indeed the deliberate retention of the archaic, which marks several epochs in the history of Chinese has often been noted. Post-war Italian, despite the pressure of verismo and the conscious modernism of other media, such as film, has been curiously inert”

“Both the French and the Bolshevik revolutions were linguistically conservative, almost academic in their rhetoric. The Second Empire, on the other hand, sees one of the principal movements of stress and exploration in the poetics and habits of sensibility of the French language. At most stages in the history of a language, moreover, innovative and conservative tendencies coexist.”

“Some who have thought hardest about the nature of language and about the interactions of speech and society – De Maistre, Karl Kraus, Walter Benjamin, George Orwell – have, consciously or not, argued from a vitalist metaphor. In certain civilizations there come epochs in which syntax stiffens, in which the available resources of live perception and restatement wither. Words seem to go dead under the weight of sanctified usage; the frequency and sclerotic force of clichés, of unexamined similes, of worn tropes increases. Instead of acting as a living membrane, grammar and vocabulary become a barrier to new feeling. A civilization is imprisoned in a linguistic contour which no longer matches, or matches only at certain ritual; arbitrary points, the changing landscape of fact.”

“Worn, threadbare, filed down, words have become the carcass of words, phantom words; everyone drearily chews and regurgitates the sound of them between their jaws.” Adamov

“The totality of Homer, the capacity of the Iliad and Odyssey to serve as repertoire for most of the principal postures of Western consciousness – we are petulant as Achilles and old as Nestor, our homecomings are those of Odysseus – point to a moment of singular linguistic energy.”

“Aeschylus may not only have been the greatest of tragedians but the creator of the genre, the first to locate in dialogue the supreme intensities of human conflict. The grammar of the Prophets in Isaiah enacts a profound metaphysical scandal – the enforcement of the future tense, the extension of language over time. A reverse discovery animates Thucydides; his was the explicit realization that the past is a language construct, that the past tense of the verb is the sole guarantor of history. The formidable gaiety of the Platonic dialogues, the use of the dialectic as a method of intellectual chase, stems from the discovery that words, stringently tested, allowed to clash as in combat or manoeuvre as in a dance, will produce new shapes of understanding. Who was the first man to tell a joke, to strike laughter out of speech (the absence of jokes from Old Testament writings suggests that purely verbal wit may be a fairly late, subversive development)?”

“It is difficult to suppose that the Oresteia was composed very long after the dramatist’s first awareness of the paradoxical relations between himself, his personages, and the fact of personal death.”

“We have histories of massacre and deception, but none of metaphor. We cannot accurately conceive what it must have been like to be the first to compare the colour of the sea with the dark of wine or to see autumn in a man’s face. Such figures are new mappings of the world, they reorganize our habitation in reality.” “No desolation has gone deeper than Job’s, no dissent from mundanity has been more trenchant than Antigone’s. The fire-light in the domestic hearth at close of day was seen by Horace; Catullus came near to making an inventory of sexual desire. A great part of Western art and literature is a set of variations on definitive themes. Hence the anarchic bitterness of the late-comer and the impeccable logic of Dada when it proclaims that no new impulses of feeling or recognition will arise until language is demolished. <Make all things new> cries the revolutionary, in words as old as the Song of Deborah or the fragments of Heraclitus.”

“ethno-linguists tell us, for example, that Tarascan, a Mexican tongue, is inhospitable to new metaphors, whereas Cuna, a Panamanian language, is avid for them. An Attic delight in words, in the play of rhetoric, was noticed and often mocked throughout the Mediterranean world. Qiryat Sepher, the <City of the Letter> in Palestine, and the Syrian Byblos, the <Town of the Book>, are designations with no true parallel anywhere else in the ancient world.”

“In numerous cultures blindness is a supreme infirmity and abdication from life; in Greek mythology the poet and the seer are blind so that they may, by the antennae of speech, see further.”

“A true reader is a dictionary addict. He knows that English is particularly well served, from Bosworth’s Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, through Kurath and Kuhn’s Middle English Dictionary to the almost incomparable resources of the O.E.D. (both Grimm’s Wörterbuch and the Littré are invaluable but neither French nor German have found their history and specific genius as completely argued and crystallized in a single lexicon).”

“Rossetti’s geomaunt will lead to Shipley’s Dictionary of Early English and the reassurance that <the topic is capped with moromancy, foolish divination, a 17th century term that covers them all>. Skeat’s Etymological Dictionary and Principles of English Etymology are an indispensable first step towards grasping the life of words. But each period has its specialized topography. Skeat and Mayhew’s Glossary of Tudor and Stuart Words necessarily accompanies one’s reading of English literature from Skelton to Marvell. No one will get to the heart of the Kipling world, or indeed clear up certain cruces in Gilbert and Sullivan without Sir H. Yule and A. C. Burnell’s Hobson-jobson. Dictionaries of proverbs and place-names are essential. Behind the façade of public discourse extends the complex, shifting terrain of slang and taboo speech. Without such quarries as Champion’s L’Argot ancien and Eric Partridge’s lexica of underworld usage, much of Western literature, from Villon to Genet is only partly legible.

Beyond such major taxonomies lie areas of relevant specialization. A demanding reader of mid-eighteenth-century verse will often find himself referring to the Royal Horticultural Society’s Dictionary of Gardening. The old Drapers’ Dictionary of S. William Beck clears up more than one erotic conundrum in Restoration comedy. Fox-Davies’s Armorial Families and other registers of heraldry are as helpful at the opening of The Merry Wives of Windsor as they are in elucidating passages in the poetry of Sir Walter Scott. A true Shakespeare library is, of itself, very nearly a summation of human enterprise. It would include manuals of falconry and navigation, of law and of medicine, of venery [caça] and the occult. A central image in Hamlet depends on the vocabulary of wool-dyeing [tecedura de lã] (wool greased or enseamed with hog’s lard over the nasty sty [quer dizer que a lã em comento foi banhada com gordura e resinas de intestino de porco]); from The Taming of the Shrew [A Megera Domada] to The Tempest, there is scarcely a Shakespearean play which does not use the extensive glossary of Elizabethan musical terms to make vital statements about human motive or conduct. Several episodes in Jane Austen can only be made out if one has knowledge, not easily come by, of a Regency escritoire and of how letters were sent. Being so physically cumulative in effect, so scenic in structure, the Dickens world draws on a great range of technicality. There is a thesaurus of Victorian legal practice and finance in Bleak House and Dombey and Son. The Admiralty’s Dictionary of Naval Equivalents and a manual of Victorian steam-turbine construction have helped clear up the meaning of one of the most vivid yet hermetic similes in The Wreck of the Deutschland.”

“The complete penetrative grasp of a text, the complete discovery and recreative apprehension of its life-forms (prise de conscience), is an act whose realization can be precisely felt but is nearly impossible to paraphrase or systematize.” “To read Shakespeare and Hölderlin is, literally, to prepare to read them. But neither erudition nor industry make up the sum of insight, the intuitive thrust to the centre.” “yet more is needed: just literary perception, congenial intimacy with the author, experience which must have been won by study, and mother wit which he must have brought from his mother’s womb.” Houman

“ainda mais (do que erudição e indústria) são necessários: percepção literária na medida, intimidade congênita com o autor, experiência esta ganha também por estudo, mas que em não poucos casos deriva de <inteligência de mãe> que deve haver desde o útero na pessoa.”

“Ter crítica de conjectura, que permite emendar um autor que está sendo traduzido, é mais do que se pode esperar do gênero humano, sobretudo em se tratando de Shakespeare” Johnson

“Ultimate connoisseurship is a kind of finite mimesis: through it the painting or the literary text is made new – though obviously in that reflected, dependent sense which Plato gave to the concept of <imitation>.”

“Every musical realization is a new poiesis. It differs from all other performances of the same composition. Its ontological relationship to the original score and to all previous renditions is twofold: it is at the same time reproductive and innovatory. In what sense does unperformed music exist? But what is the measure of the composer’s verifiable intent after successive performances? There is a strain of femininity [?] in the great interpreter, a submission, made active by intensity of response, to the creative presence.”

Je est un autre

“Literature is news that stays news” Ezra Pound

“Só a grande arte sobrevive a uma exaustiva e deliberada reinterpretação.”

“Each time Cymheline is staged, Posthumus’s monologue becomes the object of manifold <edition>. An actor can choose to deliver the words of the Folio in what is thought to have been the pronunciation of Elizabethan English. He can adopt a neutral, though in fact basically nineteenth-century solemn register and vibrato (the equivalent of a Victorian prize calf binding). He may by control of caesura and vowel-pitch convey an impression of modernity. His – the producer’s – choice of costume is an act of practical criticism. A Roman Posthumus represents a correction of Elizabethan habits of anachronism or symbolic contemporaneity – themselves a convention of feeling which we may not fully grasp. A Jacobean costume points to the location of the play in a unique corpus: it declares of Cymheline that Shakespeare’s authorship is the dominant fact.”

“When we read or hear any language-statement from the past, be it Leviticus or last year’s best-seller, we translate. Reader, actor, editor are translators of language out of time.”

“The time-barrier may be more intractable than that of linguistic difference. Any bilingual translator is acquainted with the phenomenon of <false friends> – homonyms such as French hahit and English habit which on occasion might, but almost never do, have the same meaning, or mutually untranslatable cognates such as English home and German Heim.”

“What material reality has history outside language, outside our interpretative belief in essentially linguistic records (silence knows no history)? Where worms, fires of London, or totalitarian régimes obliterate such records, our consciousness of past being comes on a blank space. To remember everything is a condition of madness. We remember culturally, as we do individually, by conventions of emphasis, foreshortening, and omission.”

“The Middle Ages experienced by Walter Scott were not those mimed by the Pre-Raphaelites. The Augustan paradigm of Rome was, like that of Ben Janson and the Elizabethan Senecans, an active fiction, a <reading into life>. But the two models were very different. From Marsilio Ficino to Freud, the image of Greece, the verbal icon made up of successive translations of Greek literature, history, and philosophy, has oriented certain fundamental movements in Western feeling. But each reading, each translation differs, each is undertaken from a distinctive angle of vision. The Platonism of the Renaissance is not that of Shelley, Hölderlin’s Oedipus is not the Everyman of Freud or the limping [deficiente; muito debilitado] shaman of Lévi-Strauss.”

“There is, today, a 1914-19 figura for those in their 70s; to a man of 40, 1914 is the vague forerunner of realities which only gather meaning in the crises of the late 1930s; to the <bomb-generation>, history is an experience that dates to 1945; what lies before is an allegory of antique illusions. In the recent revolts of the very young, a surrealistic syntax, anticipated by Artaud and Jarry, is at work: the past tense is to be excluded from the grammar of politics and private consciousness.”

“This metaphysic of the instant, this slamming of the door on the long galleries of historical consciousness, is understandable. It has a fierce innocence. It embodies yet another surge towards Eden, towards that pastoral before time (there could be no autumn before the apple was off the branch, no fall before the Fall) which the eighteenth century sought in the allegedly static cultures of the south Pacific. But it is an innocence as destructive of civilization as it is, by concomitant logic, destructive of literate speech. Without the true fiction of history, without the unbroken animation of a chosen past, we become flat shadows. Literature, whose genius stems from what Éluard [um dos fundadores do surrealismo] called le dur désir de durer, has no chance of life outside constant translation within its own language. Art dies when we lose or ignore the conventions by which it can be read, by which its semantic statement can be carried over into our own idiom”

“Languages that extend over a large physical terrain will engender regional modes and dialects. Before the erosive standardizations of radio and television became effective, it was a phonetician’s parlour-trick to locate, often to within a few dozen miles, the place of origin of an American from the border states or a north-country Englishman. The mutual incomprehensibility of diverse branches of Chinese such as Cantonese and Mandarin are notorious. There are dictionaries and grammars of Venetian, Neapolitan, and Bergamasque.”

“Different castes, different strata of society use a different idiom. Eighteenth-century Mongolia provides a famous case. The religious language was Tibetan; the language of government was Manchu; merchants spoke Chinese; classical Mongol was the literary idiom; and the vernacular was the Khalka dialect of Mongol.”

Michel Leiris, La Langue secrète des Dogons de Sanga (Soudan Français) (Paris, 1948)

“Upper-class English diction, with its sharpened vowels, elisions; and modish slurs, is both a code for mutual recognition – accent is worn like a coat of arms – and an instrument of ironic exclusion. It communicates from above, enmeshing the actual unit of information, often imperative or conventionally benevolent, in a network of superfluous linguistic matter.” “Thackeray and Wodehouse are masters at conveying this dual focus of aristocratic semantics. As analysed by Proust, the discourse of Charlus is a light-beam pin-pointed, obscured, prismatically scattered as by a Japanese fan beating before a speaker’s face in ceremonious motion. To the lower classes, speech is no less a weapon and a vengeance.”

William Labor, Paul Cohen & Clarence Robbins, A Preliminary Study of English, Used by Negro and Puerto Rican Speakers in New York City (New York, 1965)

“White and black trade words as do front-line soldiers lobbing back an undetonated grenade.”

“Competing ideologies rarely create new terminologies. As Kenneth Burke and George Orwell have shown in regard to the vocabulary of Nazism and Stalinism, they pilfer and decompose the vulgate. In the idiom of fascism and communism, peace, freedom, progress, popular will are as prominent as in the language of representative democracy. But they have their fiercely disparate meanings. The words of the adversary are appropriated and hurled against him. When antithetical meanings are forced upon the same word (Orwell’s Newspeak), when the conceptual reach and valuation of a word can be altered by political decree, language loses credibility. Translation in the ordinary sense becomes impossible. To translate a Stalinist text on peace or on freedom under proletarian dictatorship into a non-Stalinist idiom, using the same time-honoured words, is to produce a polemic gloss, a counter-statement of values. At the moment, the speech of politics, of social dissent, of journalism is full of loud ghost-words, being shouted back and forth, signifying contraries or nothing. It is only in the underground of political humour that these shibboleths [matizes, jargões, lugares-comuns] regain significance. When the entry of foreign tanks into a free city is glossed as <a spontaneous, ardently welcomed defence of popular freedom> (Izvestia, 27 August 1968), the word <freedom> will preserve its common meaning only in the clandestine dictionary of laughter.”

“Japanese children employ a separate vocabulary for everything they have and use up to a certain age. More common, indeed universal, is the case in which children carve their own language-world out of the total lexical and syntactic resources of adult society.”

“The scatological doggerels of the nursery and the alley-way may have a sociological rather than a psychoanalytic motive. The sexual slang of childhood, so often based on mythical readings of actual sexual reality rather than on any physiological grasp, represents a night-raid on adult territory. The fracture of words, the maltreatment of grammatical norms which, as the Opies have shown, constitute a vital part of the lore, mnemonics, and secret parlance of childhood, have a rebellious aim: by refusing, for a time, to accept the rules of grown-up speech, the child seeks to keep the world open to his own, seemingly unprecedented needs. In the event of autism, the speech-battle between child and master can reach a grim finality. Surrounded by incomprehensible or hostile reality, the autistic child breaks off verbal contact. He seems to choose silence to shield his identity but even more, perhaps, to destroy his imagined enemy. Like murderous Cordelia, children know that silence can destroy another human being. Or like Kafka they remember that several have survived the song of the Sirens, but none their silence.” “Diderot had referred to <l’enfant, ce petit sauvage>, joining under one rubric the nursery and the natives of the South Seas.”

“The passage from the transitional into the exploratory model is visible in Lewis Carroll. Alice in Wonderland relates to voyages into the language-world and special logic of the child as Gulliver relates to the travel literature of the Enlightenment.”

“Henry James was one of the true pioneers. He made an acute study of the frontier zones in which the speech of children meets that of grown-ups. The Pupil dramatizes the contrasting truth-functions in adult idiom and the syntax of a child. Children, too, have their conventions of falsehood, but they differ from ours. In The Turn of the Screw, whose venue is itself so suggestive of an infected Eden, irreconcilable semantic systems destroy human contact and make it impossible to locate reality. This cruel fable moves on at least four levels of language: there is the provisional key of the narrator (I), initiating all possibilities but stabilizing none, there is the fluency of the governess (II), with its curious gusts of theatrical bravura, and the speech of the servants so avaricious of insight (III). These three modes envelope, qualify, and obscure that of the children (IV). Soon incomplete sentences, filched letters, snatches of overheard but misconstrued speech, produce a nightmare of untranslatability. <I said things,> confesses Miles when pressed to the limit of endurance. That tautology is all his luminous, incomprehensible idiom can yield. The governess seizes upon <an exquisite pathos of contradiction>. Death is the only plain statement left. Both The Awkward Age and What Maisie Knew focus on children at the border, on the brusque revelations and bursts of static which mark the communication between adolescents and those adults whose language-territory they are about to enter.”

“But for all their lively truth, children in the novels of James and Dostoevsky remain, in large measure, miniature adults. They exhibit the uncanny percipience of the <aged> infant Christ in Flemish art. Mark Twain’s transcriptions of the secret and public idiom of childhood penetrate much further. A genius for receptive insight animates the rendition of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer.” “For the first time in Western literature, the linguistic terrain of childhood was mapped without being laid waste. After Mark Twain, child psychology and Piaget could proceed.

“Sybil released her foot. <Did you read ‘Little Black Sambo’?> she said.

<It’s very funny you ask me that,> he said. <It so happens I just finished reading it last night.> He reached down and took back Sybil’s hand. <What did you think of it?> he asked her.

<Did the tigers run all around that tree?>

<I thought they’d never stop. I never saw so many tigers.>

<There were only six,> Sybil said.

<Only six!> said the young man. <Do you call that only?>

<Do you like wax?> Sybil asked.

<Do I like what?> asked the young man.

<Wax.>

<Very much. Don’t you?>

Sybil nodded. <Do you like olives?> she asked.

<Olives–yes. Olives and wax. I never go anyplace without ‘em.>

Sybil was silent.

<I like to chew candles,> she said finally.

<Who doesn’t?> said the young man, getting his feet wet.”

J.D. Salinger

“Hence the argument of modern anthropology that the incest taboo, which appears to be primal to the organization of communal life, is inseparable from linguistic evolution. We can only prohibit that which we can name. Kinship systems, which are the coding and classification of sex for purposes of social survival, are analogous with syntax. The seminal and the semantic functions (is there, ultimately, an etymological link?) determine the genetic and social structure of human experience. Together they construe the grammar of being.”

AGE OF MASTURBATION

“If coition can be schematized as dialogue, masturbation seems to be correlative with the pulse of monologue or of internalized address. There is evidence that the sexual discharge in male onanism is greater than it is in intercourse.”

“Ejaculation [expelir com força; falar] is at once a physiological and a linguistic concept. Impotence and speech-blocks [gagueira], premature emission [ejaculação precoce – <gente que interrompe a fala do outro>, cof, cof…] and stuttering, involuntary ejaculation and the word-river of dreams are phenomena whose interrelations seem to lead back to the central knot of our humanity. Semen, excreta, and words are communicative products. They are transmissions from the self inside the skin to reality outside. At the far root, their symbolic significance, the rites, taboos, and fantasies which they evoke, and certain of the social controls on their use, are inextricably interwoven. We know all this but hardly grasp its implications.”

Semen

See, man

Seaman

Zimmerman

“In what measure are sexual perversions analogues of incorrect speech? Are there affinities between pathological erotic compulsions and the search, obsessive in certain poets and logicians, for a <private language>, for a linguistic system unique to the needs and perceptions of the user? Might there be elements of homosexuality in the modem theory of language (particularly in the early Wittgenstein), in the concept of communication as an arbitrary mirroring? It may be that the significance of Sade lies in his terrible loquacity, in his forced outpouring of millions of words. In part, the genesis of sadism could be linguistic. The sadist makes an abstraction of the human being he tortures; he verbalizes life to an extreme degree by carrying out on living beings the totality of his articulate fantasies. Did Sade’s uncontrollable fluency, like the garrulousness [tagarelice] often imputed to the old, represent a psycho-physiological surrogate for diminished sexuality (pornography seeking to replace sex by language)?”

“The formal duality of men’s and women’s speech has been recorded also in Eskimo languages, in Carib, a South American Indian language, and in Thai. I suspect that such division is a feature of almost all languages at some stage in their evolution and that numerous spoors of sexually determined lexical and syntactical differences are as yet unnoticed. But again, as in the case of Japanese or Cherokee <child-speech>, formal discriminations are easy to locate and describe. The far more important, indeed universal phenomenon, is the differential use by men and women of identical words and grammatical constructs.”

“At a rough guess, women’s speech is richer than men’s in those shadings of desire and futurity known in Greek and Sanskrit as optative; women seem to verbalize a wider range of qualified resolve and masked promise. Feminine uses of the subjunctive in European languages give to material facts and relations a characteristic vibrato. I do not say they lie about the obtuse, resistant fabric of the world: they multiply the facets of reality, they strengthen the adjective. To allow it an alternative nominal status, in a way which men often find unnerving. There is a strain of ultimatum, a separatist stance, in the masculine intonation of the first-person pronoun; the <I> of women intimates a more patient bearing, or did until Women’s Liberation. The two language models follow on Robert Graves’ dictum that men do but women are.

In regard to speech habits, the headings of mutual reproach are immemorial. In every known culture, men have accused women of being garrulous, of wasting words with lunatic prodigality. The chattering, ranting, gossipping female, the tattle, the scold, the toothless crone her mouth wind-full of speech, is older than fairy-tales. Juvenal, in his Sixth Satire, makes a nightmare of woman’s verbosity:

The grammarians yield to her; the rhetoricians succumb; the whole crowd is silenced. No lawyer, no auctioneer will get a word in, no, nor any other woman. Her speech pours out in such a torrent that you would think that pots and bells were being banged together. Let no one more blow a trumpet or clash a cymbal: one woman alone will make noise enough to rescue the labouring moon (from eclipse).”

“The alleged outpouring of women’s speech, the rank flow of words, may be a symbolic restatement of men’s apprehensive, often ignorant awareness of the menstrual cycle. In masculine satire, the obscure currents and secretions of woman’s physiology are an obsessive theme. Ben Jonson unifies the two motifs of linguistic and sexual incontinence in The Silent Woman. <She is like a conduit-pipe>, says Morose of his spurious bride, <that will gush out with more force when she opens again.> <Conduit-pipe>, with its connotations of ordure and evacuation, is appallingly brutal. So is the whole play. The climax of the play again equates feminine verbosity with lewdness: <O my heart! wilt thou break? wilt thou break? this is worst of all worst worsts that hell could have devised! Marry a whore, and so much noise!>”

“The motif of the woman or maiden who says very little, in whom silence is a symbolic counterpart to chasteness and sacrificial grace, lends a unique pathos to the Antigone of Oedipus at Colonus or Euripides’ Alcestis.” “These values crystallize in Coriolanus’ salute to Virgilia: <My gracious silence, hail!> The line is magical in its music and suggestion, but also in its dramatic shrewdness.”

“Women know the change in a man’s voice, the crowding of cadence, the heightened fluency triggered off by sexual excitement. They have also heard, perennially, how a man’s speech flattens, how its intonations dull after orgasm. In feminine speech-mythology, man is not only an erotic liar; he is an incorrigible braggart. Women’s lore and secret mock record him as an eternal miles gloriosus, a self-trumpeter who uses language to cover up his sexual or professional fiascos, his infantile needs, his inability to withstand physical pain.”

“Taceat mulier in ecclesia is prescriptive in both Judaic and Christian culture.”

“Like breathing, the technique is unconscious; like breathing also, it is subject to obstruction and homicidal breakdown. Under stress of hatred, of boredom, of sudden panic, great gaps open. It is as if a man and a woman then heard each other for the first time and knew, with sickening conviction, that they share no common language, that their previous understanding had been based on a trivial pidgin which had left the heart of meaning untouched. Abruptly the wires are down and the nervous pulse under the skin is laid bare in mutual incomprehension. Strindberg is master of such moments of fission. Harold Pinter’s plays locate the pools of silence that follow.”

“Like no other playwright, Racine communicates not only the essential beat of women’s diction but makes us feel what there is in the idiom of men which Andromaque, Phèdre, or Iphigénie can only grasp as falsehood or menace. Hence the equivocation, central in his work, on the twofold sense of entendre [em francês, escutar antes que entender]: these virtuosos of statement hear each other perfectly, but do not, cannot apprehend. I do not believe there is a more complete drama in literature, a work more exhaustive of the possibilities of human conflict than Racine’s Bérénice. It is a play about the fatality of the coexistence of man and woman, and it is dominated, necessarily, by speech-terms (parole, dire, mot, entendre). Mozart possessed something of this same rare duality (so different from the characterizing, polarizing drive of Shakespeare). Elvira, Donna Anna, and Zerlina have an intensely shared femininity, but the music exactly defines their individual range or pitch of being. The same delicacy of tone-discrimination is established between the Countess and Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro. In this instance, the discrimination is made even more precise and more dramatically different from that which characterizes male voices by the <bisexual> role of Cherubino. The Count’s page is a graphic example of Lévi-Strauss’ contention that women and words are analogous media of exchange in the grammar of social life. Stendhal was a careful student of Mozart’s operas. That study is borne out in the depth and fairness of his treatment of the speech-worlds of men and women in Fabrice and la Sanseverina in The Charterhouse of Parma. Today, when there is sexual frankness as never before, such fairness is, paradoxically, rarer. It is not as <translators> that women novelists and poets excel, but as declaimers of their own, long-stifled tongue.”

“Não é como tradutoras que as mulheres que são novelistas e poetas sobressaem-se, mas como declamadoras de seu próprio eu, seu próprio sexo, seus discursos longamente interrompidos e abortados.”

“The <aside> as it is used in drama is a naïve representation of scission: the speaker communicates to himself (thus to his audience) all that his overt statement to another character leaves unsaid. As we grow intimate with other men or women, we often <hear> in the slightly altered cadence, speed, or intonation of whatever they are saying to us the true movement of articulate but unvoiced intent. Shakespeare’s awareness of this twofold motion is unfailing. Desdemona asks of Othello, in the very first, scarcely realized instant of shaken trust, <Why is your speech so faint?>.”

“Having kept the same word-signals bounding and rebounding between them like jugglers’ weights, year after year, from horizon to horizon, Beckett’s vagrants and knit couples understand one another almost osmotically. With intimacy, the external vulgate and the private mass of language grow more and more concordant. Soon the private dimension penetrates and takes over the customary forms of public exchange. The stuffed-animal and baby-speech of adult lovers reflects this take-over. In old age the impulse towards translation wanes and the pointers of reference turn inward. The old listen less or principally to themselves. Their dictionary is, increasingly, one of private remembrance.”

“The affair at Babel confirmed and externalized the never-ending task of the translator – it did not initiate it.”

Babel caiu e abandonei a comunhão com o cão dentro de mim.

“Theories of semantics, constructs of universal and transformational grammar that have nothing of substance to say about the prodigality of the language atlas–more than a thousand different languages are spoken in New Guinea–could well be deceptive. It is here, rather than in the problem of the invention and understanding of melody (though the two issues may be congruent), that I would place what Lévi-Strauss calls le mystère suprême of anthropology.”

“why does this unified, though individually unique mammalian species not use one common language? It inhales, for its life processes, one chemical element and dies if deprived of it. It makes do with the same number of teeth and vertebrae. To grasp how notable the situation is, we must make a modest leap of imagination, asking, as it were, from outside. In the light of anatomical and neurophysiological universals, a unitary language solution would be readily understandable. Indeed, if we lived inside one common language-skin, any other situation would appear very odd. It would have the status of a recondite fantasy, like the anaerobic or anti-gravitational creatures in science-fiction.”

“Depending on which classification they adopt, ethnographers divide the human species into 4 or 7 races (though the term is, of course, an unsatisfactory shorthand). The comparative anatomy of bone structures and sizes leads to the use of 3 main typologies. The analysis of human blood-types, itself a topic of great intricacy and historical consequence, suggests that there are approximately half a dozen varieties. Such would seem to be the cardinal numbers of salient differentiation within the species though the individual, obviously, is genetically unique.”

“We do not speak one language, nor half a dozen, nor twenty or thirty. Four to five thousand languages are thought to be in current use. This figure is almost certainly on the low side. We have, until now, no language atlas which can claim to be anywhere near exhaustive. Furthermore, the four to five thousand living languages are themselves the remnant of a much larger number spoken in the past. Each year so-called rare languages, tongues spoken by isolated or moribund ethnic communities, become extinct. Today entire families of language survive only in the halting remembrance of aged, individual informants (who, by virtue of their singularity are difficult to cross-check) or in the limbo of tape-recordings. Almost at every moment in time, notably in the sphere of American Indian speech, some ancient and rich expression of articulate being is lapsing into irretrievable silence. One can only guess at the extent of lost languages. It seems reasonable to assert that the human species developed and made use of at least twice the number we can record today. A genuine philosophy of language and socio-psychology of verbal acts must grapple with the phenomenon and rationale of the human <invention> and retention of anywhere between five and ten thousand distinct tongues.” “To speak seriously of translation one must first consider the possible meanings of Babel, their inherence in language and mind.”

“Despite decades of comparative philological study and taxonomy, no linguist is certain of the language atlas of the Caucasus, stretching from Bzedux in the north-west to Rut’ul and Küri in the Tartar regions of Azerbeidjan.” “Arci, a language with a distinctive phonetic and morphological structure, is spoken by only one village of approximately 850 inhabitants.” “A comparable multiplicity and diversity marks the so-called Palaeosiberian language families. Eroded by Russian during the nineteenth century, Kamtchadal, a language of undeniable resource and antiquity, survives in only 8 hamlets [povoados – ‘hamlet’ seria um vilarejo tão pequeno que sequer possui paróquia] in the maritime province of Koriak.” “For Mexico and Central America alone, current listings reckon 190 distinct tongues.” “Tubatulabal was spoken by something like a thousand Indians at the southern spur of the Sierra Nevada as recently as the 1770s.” “Blank spaces and question marks cover immense tracts of the linguistic geography of the Amazon basin and the savannah. At latest count, ethno-linguists discriminate between 109 families, many with multiple sub-classes. But scores of Indian tongues remain unidentified or resist inclusion in any agreed category.” “Many will dim into oblivion before rudimentary grammars or word-lists can be salvaged. Each takes with it a storehouse of consciousness.” “The language catalogue begins with Aba, an Altaic idiom spoken by Tartars, and ends with Zyriene, a Finno-Ugaritic speech in use between the Urals and the Arctic shore. It conveys an image of man as a language animal of implausible variety and waste. By comparison, the classification of different types of stars, planets, and asteroids runs to a mere handful.”

ME WHITE MAN YOU TROUBLE M’AN MONEY KING WORLD ME OWN: “We have no sound basis [base sonora e base segura, belo trocadilho!] on which to argue that extinct languages failed their speakers, that only the most comprehensive or those with the greatest wealth of grammatical means have endured. On the contrary: a number of dead languages are among the obvious splendours of human intelligence. Many a linguistic mastodon is a more finely articulated, more <advanced> piece of life than its descendants. There appears to be no correlation, moreover, between linguistic wealth and other resources of a community. Idioms of fantastic elaboration and refinement coexist with utterly primitive, economically harsh modes of subsistence. Often, cultures seem to expend on their vocabulary and syntax acquisitive energies and ostentations entirely lacking in their material lives. Linguistic riches seem to act as a compensatory mechanism. Starving bands of Amazonian Indians may lavish on their condition more verb tenses than could Plato.”

“With the simple addition of neologisms and borrowed words, any language can be used fairly efficiently anywhere; Eskimo syntax is appropriate to the Sahara. Far from being economic and demonstrably advantageous, the immense number and variety of human idioms, together with the fact of mutual incomprehensibility, is a powerful obstacle to the material and social progress of the species. We will come back to the key question of whether or not linguistic differentiations may provide certain psychic, poetic benefits.”

“It was before Humboldt that the mystery of many tongues on which a view of translation hinges fascinated the religious and philosophic imagination.”

Arno Borst, Der Turmbau von Babel: Geschichte der Meinungen über Ursprung und Vielfalt der Sprachen und Völker (Stuttgart, 1957-63).

O Cãos de Pã-Dora

“Thus Babel was a second Fall, in some regards as desolate as the first. Adam had been driven from the garden; now men were harried, like yelping dogs, out of the single family of man. And they were exiled from the assurance of being able to grasp and communicate reality.”

“Had there not been a partial redemption at Pentecost, when the gift of tongues descended on the Apostles? Was not the whole of man’s linguistic history, as certain Kabbalists supposed, a laborious swing of the pendulum between Babel and a return to unison in some messianic moment of restored understanding?” “Jewish gnostics argued that the Hebrew of the Torah was God’s undoubted idiom, though man no longer understood its full, esoteric meaning. Other inquirers, from Paracelsus to the 17th century Pietists, were prepared to view Hebrew as a uniquely privileged language, but itself corrupted by, the Fall and only obscurely revelatory of the Divine presence. Almost all linguistic mythologies, from Brahmin wisdom to Celtic and North African lore, concurred in believing that original speech had shivered into 72 shards, or into a number which was a simple multiple of 72.” “[Nota] The 6×12 component suggests an astronomical or seasonal correlation.” “The name of Esperanto has in it, undisguised, the root for an ancient and compelling hope.”

Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism

“Starting with Genesis 11:11 and continuing to Wittgenstein’s Investigations or Noam Chomsky’s earliest, unpublished paper on morphophonemics in Hebrew, Jewish thought has played a pronounced role in linguistic mystique, scholarship, and philosophy.”

“the Talmud had said: <the omission or the addition of one letter might mean the destruction of the whole world.>”

“Elohim, the name of God, unites Mi, the hidden subject, with Eloh, the hidden object.”

“in Hebrew, and particularly in Exodus with its 72 designations of the Divine name, magic forces were compacted.”

“There was, as Coleridge knew, no deeper dreamer on language, no sensibility more haunted by the alchemy of speech, than Jakob Böhme (1575-1624). Like Nicholas of Cusa long before him, Böhme supposed that the primal tongue had not been Hebrew, but an idiom brushed from men’s lips in the instant of the catastrophe at Babel and now irretrievably dejected among all living speech (Nettesheim had, at one point, argued that Adam’s true vernacular was Aramaic).”

“In the visionary musings of Angelus Silesius (Johann Scheffler), Böhme’s intimations are carried to extremes. Angelus Silesius asserts that God has, from the beginning of time, uttered only a single word. In that single utterance all reality is contained. The cosmic Word cannot be found in any known tongue; language after Babel cannot lead back to it. The bruit of human voices, so mysteriously diverse and mutually baffling, shuts out the sound of the Logos. There is no access except silence. Thus, for Silesius, the deaf and dumb are nearest of all living men to the lost vulgate of Eden.

In the climate of the eighteenth century these gnostic reveries faded. But we find them again, changed into model and metaphor, in the work of three modem writers. It is these writers who seem to tell us most of the inward springs of language and translation.”

“Walter Benjamin’s Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers dates from 1923. An English translation of this essay, by James Hynd and E.M. Valk, may be found in Delos, A Journal on and of Translation, 2 (1968).”

“The relevant proposition is this: if translation is a form, then the condition of translatability must be ontologically necessary to certain works.” W.B.

“Translation is both possible and impossible – a dialectical antinomy characteristic of esoteric argument.” “At the <messianic end of their history> (again a Kabbalistic or Hasidic formulation), all separate languages will return to their source of common life. In the interim, translation has a task of profound philosophic, ethical, and magical import.”

“Certain of Luther’s versions of the Psalms, Hölderlin’s recasting of Pindar’s Third Pythian Ode, point by their strangeness of evocatory inference to the reality of an Ur-Sprache in which German and Hebrew or German and ancient Greek are somehow fused.”

“Marianne Moore’s readings of La Fontaine are thorn-hedges apart from colloquial American English. The translator enriches his tongue by allowing the source language to penetrate and modify it.” “As the Kabbalist seeks the forms of God’s occult design in the groupings of letters and words, so the philosopher of language will seek in translations – in what they omit as much as in their content – the far light of original meaning.”

“His loyalties divided between Czech and German, his sensibility drawn as it was, at moments, to Hebrew and to Yiddish, Kafka developed an obsessive awareness of the opaqueness of language. His work can be construed as a continuous parable on the impossibility of genuine human communication, or, as he put it to Max Brod in 1921, on <the impossibility of not writing, the impossibility of writing in German, the impossibility of writing differently. One could almost add a fourth impossibility: the impossibility of writing>.” “In the Penal Colony, perhaps the most desperate of his metaphoric reflections on the ultimately inhuman nature of the written word, Kafka makes of the printing press an instrument of torture. The theme of Babel haunted him: there are references to it in almost every one of his major tales. Twice he offered specific commentaries, in a style modelled on that of Hasidic and Talmudic exegesis”

“As no generation of men can hope to complete the high edifice, as engineering skills are constantly growing, there is time to spare. More and more energies are diverted to the erection and embellishment of the workers’ housing. Fierce broils occur between different nations assembled on the site. <Added to which was the fact that already the second or third generation recognized the meaninglessness, the futility (die Sinnlosigkeit) of building a Tower unto Heaven – but all had become too involved with each other to quit the city.> Legends and ballads have come down to us telling of a fierce longing for a predestined day on which a gigantic fist will smash the builders’ city with five blows. <That is why the city has a fist in its coat of arms.>” “The Talmud, which is often Kafka’s archetype, refers to the 49 levels of meaning which must be discerned in a revealed text. [?!?!]”

A base de uma torre que chegasse ao céu teria de estar fincada nas profundezas do inferno, como o arquétipo de todas as árvores. O Minotauro-Cérbero alado aguarda na entrada cheio de respostas para nossos próprios enigmas anti-edipianos.

“Gnostic and Manichaean speculation (the word has in it an action of mirrors) provide Borges with the crucial trope of a <counter-world>. [O Espelho de Enigmas]” Borges, o Confúcio do novo milênio: somos o sonho de uma lagartixa em sua “metempsicose”-rumo-à-borboleta de um paramundo.

the thrall of time

“Borges moves with a cat’s sinewy confidence and foolery between Spanish, ancestral Portuguese, English, French, and German. He has a poets’ grip on the fibre of each. He has rendered a Northumbrian bard’s farewell to Saxon English, <a language of the dawn>. The <harsh and arduous words> of Beowulf were his before he <became a Borges>.”

“The Library of Babel dates from 1941. Every element in the fantasia has its sources in the <literalism> of the Kabbala and in gnostic and Rosicrucian images, familiar also to Mallarmé, of the world as a single, immense tome. <The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps an infinite number of hexagonal galleries.> It is a beehive out of Piranesi [artista plástico italiano do séc. XVIII] but also, as the title indicates, an interior view of the Tower. <The Library is total and . . . its shelves contain all the possible combinations of the 20-odd orthographic symbols (whose number, though vast, is not infinite); that is, everything which can be expressed, in all languages. Everything is there: the minute history of the future, the autobiographies of the archangels, the faithful catalogue of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogues, a demonstration of the falsehood of the true catalogue, the Gnostic gospel of Basilides, the commentary on this gospel, the commentary on the commentary of this gospel, the veridical account of your death, a version of each book in all languages, the interpolation of every book in all books.> Any conceivable combination of letters has already been foreseen in the Library and is certain to <encompass some terrible meaning> in one of its secret languages. No act of speech is without meaning: <No one can articulate a syllable which is not full of tenderness and fear, and which is not, in one of those languages, the powerful name of some god.> Inside the burrow or circular ruins men jabber in mutual bewilderment; yet all their myriad words are tautologies making up, in a manner unknown to the speakers, the lost cosmic syllable or Name of God. This is the formally boundless unity that underlies the fragmentation of tongues.”

“Arguably, Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote (1939) is the most acute, most concentrated commentary anyone has offered on the business of translation. What studies of translation there are, including this book, could, in Borges’ style, be termed a commentary on his commentary. This concise fiction has been widely recognized for the device of genius which it obviously is. But – and again one sounds like a pastiche of Borges’s fastidious pedantry – certain details have been missed. Menard’s bibliography is arresting: the monographs on <a poetic vocabulary of concepts> and on <connections or affinities> between the thought of Descartes, Leibniz, and John Wilkins point towards the labours of the 17th century to construe an ars signorum, a universal ideogrammatic language system. Leibniz’s Characteristica universalis, to which Menard addresses himself, is one such design; Bishop Wilkins’s Essay towards a real character and a philosophical language of 1668 another. Both are attempts to reverse the disaster at Babel. Menard’s <work sheets of a monograph on George Boole’s symbolic logic> show his (and Borges’) awareness of the connections between the 17th century pursuit of an inter-lingua for philosophic discourse and the <universalism> of modem symbolic and mathematical logic. Menard’s transposition of the decasyllables of Valéry’s Le Cimetière marin into alexandrines is a powerful, if eccentric, extension of the concept of translation. And pace the suave authority of the memorialist, I incline to believe that <a literal translation of Quevedo’s literal translation> of Saint François de Sales was, indeed, to be found among Menard’s papers.” “(How many readers of Borges have observed that Chapter IX turns on a translation from Arabic into Castilian, that there is a labyrinth in XXXVIII, and that Chapter XXII contains a literalist equivocation, in the purest Kabbalistic vein, on the fact that the word no has the same number of letters as the word sí?)” “to become Cervantes by merely fighting Moors, recovering the Catholic faith, and forgetting the history of Europe between 1602 and 1918 was really too facile a métier. Far more interesting was <to go on being Pierre Menard and reach the Quixote through the experiences of Pierre Menard>, i.e. to put oneself so deeply in tune with Cervantes’s being, with his ontological form, as to re-enact, inevitably, the exact sum of his realizations and statements. The arduousness of the game is dizzying. Menard assumes <the mysterious duty> – Bonner,(*) rightly I feel, invokes the notion of <contract> – of recreating deliberately and explicitly what was in Cervantes a spontaneous process. But although Cervantes composed freely, the shape and substance of the Quixote had a local <naturalness> and, indeed, necessity now dissipated. Hence a second fierce difficulty for Menard: to write <the Quixote at the beginning of the 17th century was a reasonable undertaking, necessary and perhaps even unavoidable; at the beginning of the 20th, it is almost impossible. It is not in vain that 300 years have gone by, filled with exceedingly complex events. Amongst them, to mention only one, is the Quixote itself> (Bonner’s <that same Don Quixote> both complicates and flattens Borges’ intimation). In other words, any genuine act of translation is, in one regard at least, a transparent absurdity, an endeavour to go backwards up the escalator of time and to re-enact voluntarily what was a contingent motion of spirit.”

(*) Tradutor anglo-saxônico deste clássico borgeano. Possivelmente, bancar uma missão desabonneradora!

“<Repetition> is, as Kierkegaard argued, a notion so puzzling that it puts in doubt causality and the stream of time.”

Qual de nós 2 escreve esta página, eu ou meu tradutor? Pois, se não é o segundo, talvez este trecho sequer exista… Eu certamente nunca vim a escrevê-lo!

Singularidades estão na [MÔ]NA[DA].

“Philology is the quintessential historical science, the key to the Scienza nuova, because the study of the evolution of language is the study of the evolution of the human mind itself.” “Vico’s opposition to Descartes and to the extensions of Aristotelian logic in Cartesian rationalism made of him the first true <linguistic historicist> or relativist.” “a universal logic of language, on the Aristotelian or Cartesian-mathematical model, is falsely reductionist.”

“Hamann throws out suggestions which anticipate the linguistic relativism of Sapir and Whorf.” “Herder was possessed of a sense of place. His Sprachphilosophie marks a translation from the inspired fantastications of Hamann to the development of genuine comparative linguistics in the early 19th century.” “An untranslated language, urges Herder, will retain its vital innocence, it will not suffer the debilitating admixture of alien blood.”

“Sir William Jones’ celebrated Third Anniversary Discourse on the Hindus of 1786 had, as Friedrich von Schlegel put it, <first brought light into the knowledge of language through the relationship and derivation he demonstrated of Roman, Greek, Germanic and Persian from Indic; and through this into the ancient history of peoples, where previously everything had been dark and confused>. Schlegel’s own Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier of 1808, which contains this tribute to Jones, itself contributed largely to the foundations of modern linguistics. It is with Schlegel that the notion of <comparative grammar> takes on clear definition and currency. Not much read today, Mme. de Staël’s De L’Allemagne (1813) [de quem Nietzsche foi orgulhosamente um detrator] exercised tremendous influence.” “Expanding on suggestions already made by Hamann, she sought to correlate the metaphysical ambience, internal divisions, and lyric bias of the German national spirit with the gnarled weave and <suspensions of action> in German syntax. She saw Napoleonic French as antithetical to German, and found its systematic directness and rhetoric clearly expressive of the virtues and vices of the French nation.”

“The play of intelligence, the delicacy of particular notation, the great front of argument which Humboldt exhibits, give his writings on language, incomplete though they are, a unique stature. Humboldt is one of the very short list of writers and thinkers on language–it would include Plato, Vico, Coleridge, Saussure, Roman Jakobson–who have said anything that is new and comprehensive.”

“Werther, Don Carlos, Faust are supreme works of the individual imagination, but also intensely pragmatic forms. In them, through them, the hitherto divided provinces and principalities of the German-speaking lands could test a new common identity. Goethe and Schiller’s theatre at Weimar, Wieland’s gathering of German ballads and folk poetry, the historical narratives and plays of Kleist set out to create in the German mind and in the language a shared echo. As Vico had imagined it would, a body of poetry gave a bond of remembrance (partially fictive) to a new national community. As he studied the relations of language and society, Humboldt could witness how a literature, produced largely by men whom he knew personally, was able to give Germany a living past, and how it could project into the future great shadowforms of idealism and ambition.”