“Despite being, perhaps along with voiceover, the most criticised (and even vilified) audiovisual translation (AVT) mode, there is little doubt that, generally speaking and from different viewpoints, dubbing works. It is still the preferred form of access to foreign-language audiovisual content for millions of viewers in countries such as Spain, Italy, France and Germany and the preferred choice to translate cartoons and children’s films in subtitling countries (Chaume 2013). Its success is not only commercial, as recent research shows that dubbing is also a very effective translation mode from a cognitive point of view (Wissmath et al. 2009; Perego et al. 2016). Despite the artifice involved in replacing the original actors’ voices for other voices in another language, it seems that (habituated) dubbing viewers still manage to suspend disbelief and become immersed in the fiction of film (Palencia 2002).”

“How do we watch a dubbed film? How do we manage to suspend disbelief without being distracted by its artificial nature and by the mismatch between audio and visual elements? In short, what cognitive mechanisms do we activate to make dubbing work?

The aim of this paper is to answer these questions by analysing, with the help of eye-tracking technology, the viewing patterns of spectators watching dubbed and original films. This analysis is complemented by a discussion of other aspects that may be relevant to the perception and overall reception of dubbing, including cultural arguments concerning habituation, psychological and cognitive notions of suspension of disbelief and perceptual phenomena such as the McGurk effect (McGurk and MacDonald 1976).”

“When they are first exposed to film, children normally have no knowledge of the artifice involved in cinematic fiction, which means that they go straight from wonder into habituation and automatism. By the time they learn about the prefabricated nature of cinema, film viewing has already settled as an unconscious experience whose enjoyment requires not questioning the reality of what they are seeing, that is, suspending disbelief. Crucially, dubbing audiences are exposed to both original and dubbed films from an early age. They are astounded by the magic of cinema (wonder), regardless of whether or not it is dubbed. The artifice of dubbing (the mismatch between audio and visuals, the almost inevitable lack of total synchrony, even in high-quality dubbing, etc.) is overlooked along with the artifice of cinematic fiction, as they go from wonder to habituation and unconscious automatism. By the time dubbing audiences learn about dubbing (just as when they learn about film), they have already internalised how to watch it without questioning it. In other words, getting used to dubbing, when it happens at an early age, is simply part of the (unconscious) process of getting used to film.”

“Even if a particular audience is used to dubbing, there is a tolerance threshold that must be respected with regard to at least two of the key dubbing constraints: synchrony and the naturalness of the dialogue. According to Rowe (1960: 117), this tolerance threshold may vary across countries:

American and English audiences are the least tolerant, followed closely by the Germans. […] The French, staunch defenders of their belle langue and accustomed to the dubbing process since those early days when rudimentary techniques made synchronization a somewhat haphazard achievement, are far more annoyed by slipshod dialogue than imperfect labial illusions. To the Italians, the play’s the thing and techniques take the hindmost, as artistically they should.”

“The notion of suspension of disbelief was originally coined in 1817 by the poet and philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge (in Parrish 1985: 106), who suggested that if a writer could provide a fantastic tale with a ‘human interest and a semblance of truth’, the reader would suspend judgement concerning the plausibility of the narrative. This term has since been used for film (Allison et al. 2013) and AVT (Bucaria 2008). Pedersen (2011: 22) applies it to subtitling, calling it a ‘contract of illusion’ or tacit agreement between the subtitler and the viewers where the latter agree to believe ‘that the subtitles are the dialogue, that what you read is actually what people say.’”

“The McGurk effect (1976) is generally regarded as one of the most powerful perceptual phenomena demonstrating the interaction between hearing and vision in speech perception. It is described by Smith et al. (2013) as ‘an auditory illusion that occurs when the perception of a phoneme’s auditory identity is changed by a concurrently played video of a mouth articulating a different phoneme.’ A typical example would involve the audio of a given phoneme (such as /ba/) dubbed over a speaker whose mouth is visually articulating another phoneme (such as /ga/). Most subjects will report hearing /da/ even though the only sound that is heard is /ba/. Discovered by Harry McGurk and John MacDonald in 1976, this phenomenon shows that speech perception is multimodal and that vision can often be more important than audio in the perception of sounds. From a neurological standpoint, the McGurk effect shows that information from the visual cortex instructs the auditory cortex which phoneme to ‘hear’ before an auditory stimulus is received (Smith et al. 2013). This is generally regarded as a robust effect, i.e. knowledge about it does not seem to eliminate its illusion. The effect has been shown to apply under very different conditions, including different viewers’ profiles (Rouger et al. 2008), audiovisual cross-dressing (combination of female faces and male voices) (Green et al. 1991), cross-cultural comparisons (Rosenblum 2010) and even speakers standing on their heads (Green 1994).”

“Could it be that dubbing viewers are amongst the few individuals who have managed to switch off the McGurk effect so as not to be distracted by the asynchronous combination of sound and image? Have they found a way to avoid being put off by the mismatch between lips and audio or do they simply not look at the lips? Should the latter be true, is this an unconscious mechanism and can the above-mentioned early-acquired habit of viewing dubbed films and the ability to suspend disbelief account for this?”

“Early studies (Buswell 1935; Yarbus 1965/1967) and also more recent research on face processing and the perception of gaze (Langton et al. 2000; Birmingham and Kingstone 2009) have shown that we tend to focus on faces and, more specifically, on eyes, when looking at other human beings. This may be partly explained by the visual saliency and social importance of eyes (Senju and Hasegawa 2005; Senju et al. 2005). However, most of this research has focused on static images, rather than dynamic viewing. Recent research performed on dynamic face viewing suggests that this attention bias may be task-dependent and not exclusive to the eyes (Gosselin and Schyns 2001). Buchan et al. (2007) found that their participants’ gaze was directed to the eyes when asked to perform emotion judgements and to the mouth when asked to recognise speech. In a recent study aiming to identify what controls gaze allocation during face perception, Võ et al. (2012: 12) concluded that there is no such thing as a general bias to look at someone’s eyes and that, at least during dynamic face viewing, ‘gaze follows function’. In other words, we seem to adjust our gaze allocation dynamically ‘for the purpose of seeking information on an event-to-event basis’ (ibid.: 11). In their study, conducted with 88 participants watching videos with close-ups of different people speaking, the mouth attracted as much as 34% of the gaze allocation. This is in line with the findings obtained by Foulsham and Sanderson (2013), who found a distribution of 71% on the eyes and 29% on the mouth in dynamic face viewing with speaking faces. The percentage of time fixating the mouth has been shown to increase when there is background noise (Buchan et al. 2012), low linguistic competence (Robinson et al. 2015) or poorly synched lips (Smith et al. 2013), which is not too dissimilar to what happens in dubbing.

In contrast with the intense scholarly activity devoted to the analysis of static and dynamic face viewing, the application of eye tracking to dubbing is still in its infancy. Vilaró and Smith (2011) compared the gaze behaviour of viewers watching an animated film in the original English audio condition, a Spanish language version with English subtitles, an English language version with Spanish subtitles and a final version dubbed into Spanish without subtitles. The participants were English speakers who did not know Spanish. The results of the study show evidence of subtitle reading in all conditions (even when they were in Spanish and therefore unhelpful for the participants) and a great deal of similarity in the exploration of peripheral objects.”

“Their results confirm the cognitive efficiency and positive reception of both AVT modalities but also that complex audiovisual material may require extra effort from the viewers so as to accelerate their reading process. To our knowledge, no research has yet analysed and compared how viewers watch faces in original and dubbed films. This is the aim of the experiment presented in this article, whose findings, along with the above-included discussions on habituation, suspension of disbelief and engagement, intend to provide a picture of how viewers make dubbing work.”

“However, excessive focus on the characters’ mouths may also put off dubbing viewers, making it difficult for them to suspend disbelief and engage with the film. As a result, the hypothesis for this experiment is that given our tendency to (a) lip read and be confused by asynchrony as per the McGurk effect and (b) look at both eyes and mouth in moving faces, we have adopted an unconscious strategy not to look at mouths in dubbing (because there is no useful information to obtained from there) in an attempt, aided by an early acquired and subconsciously internalised dubbing viewing habit, to suspend disbelief and be engaged with the dubbed fiction.”

“The first stimulus video was the 6-minute final scene (from 1:36:00 to 1:42:29) of Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942) dubbed into Spanish, of which 2 minutes (from 1:36:12 to 1:38:12) were closely analysed to detect eye movements in close-ups. A second stimulus video consisted of the original English version of the same excerpt, which was used with the control group of native English participants. Finally, the third stimulus video, used to analyse native Spanish viewers’ eye movements when watching an original film in Spanish, was a 6-minute scene (from 0:29:15 to 0:35:23) from Todo sobre mi madre (Pedro Almodóvar, 1999), of which 2 minutes (from 0:30:01 to 0:32:01) were closely analysed to detect eye movements in close-ups. Drawing on Perego et al. (2016), the videos were compared regarding their audiovisual complexity. Despite the significant difference in production year (1942 and 1999) and format (black and white vs. colour), the videos proved to be remarkably comparable regarding duration, speech rate (measured in words per minute), type-token ratio (degree of lexical variation), lexical density, syntactical complexity and number of close-ups”

“Participant’s eye movements were recorded using the standalone Tobii T120 eye tracker (Tobii Technology AB, Stockholm, Sweden) integrated in a 17-inch monitor with a 1024×768 resolution that allowed the maximisation of the stimulus display to cover the entire screen. Both the eye-tracking server and the client display application ran on Windows PCs connected via 1GB Ethernet. This eye tracker, which operates at a sampling rate of 60Hz with an accuracy of 0.5°, is unobtrusive, as it allows for a large degree of head movement and ensures natural behaviour, which is important in order to obtain ecologically valid results. During the recording time, the Tobii T120 eye tracker collects raw gaze movement data every 16.6 ms, using a filter to parse the coordinates of the movements into fixations and saccades. For the analysis, two areas of interest were drawn on those shots of the videos that featured close-ups, one covering the characters’ eyes and the other covering their mouths. When using the eye-tracking data to test the above-mentioned hypotheses, the focus was placed on 3 types of measurements that are relevant to gain knowledge of visual attention distribution: number of fixations, mean fixation duration and percentage amount of time spent on the defined areas of interest. A distinction was made between close-ups with dialogue and silent close-ups in order to ascertain whether the presence of dialogue has any impact on the viewers’ eye movements.”

“This study involved 42 participants (31 female and 11 male), mostly postgraduate students and young professionals. None of them received course credits or payment for participation. Of those 42 participants, 18 were native English and 24 were native Spanish. All of them had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. A total of 31 participants reported that they did not wear corrective lenses of any sort, seven reported that they wore contacts, and four reported that they wore glasses. Due to poor calibration and other data collection issues, the data from seven participants were discarded from the final analysis, bringing the total down to 35 (15 native English and 20 native Spanish) and dropping the number of males and females to 8 and 27, respectively. The ages of participants ranged from 25 to 60 (M = 28.00; SD = 8.55).”

“Participants sat in front of the eye tracker at a distance of 60-70 cm, the eye tracker camera’s focal length. Calibration was performed once for each participant before viewing the first video and required following nine dot targets displayed sequentially on the screen, each shrinking in diameter from 30 to 2 pixels.”

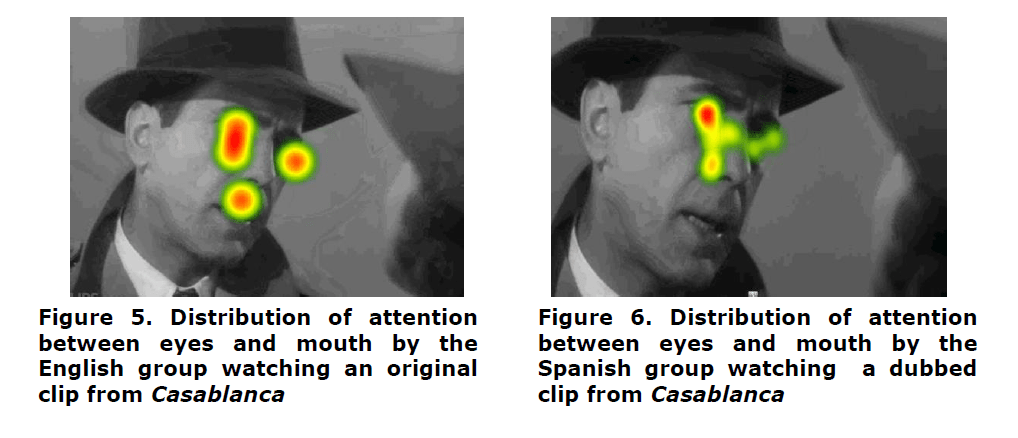

“Spanish participants watching Casablanca spent a significantly greater percentage of time looking at eyes than English participants watching Casablanca and that the same group of Spanish participants watching Todo sobre mi madre.”

“No effects were observed regarding gender or age. Comprehension was on average very high (5/5 for Casablanca in English, 4.9/5 for Casablanca in Spanish and 4.6/5 for Todo sobre mi madre) and the sense of presence may be regarded medium-high (3.6/5 for Casablanca in English, 3.7/5 for Casablanca in Spanish and 3.8/5 for Todo sobre mi madre).”

“the viewing patterns of the Spanish participants watching Casablanca dubbed into Spanish are significantly different: 95% on eyes and 5% on mouths. This extreme focus on the eyes/negative mouth bias is unlike anything found so far in the literature and very different to the way in which the Spanish participants view faces in the original Spanish film used in the experiment, where, after watching the dubbed clip, they show the same distribution (76% vs 24%) found in the literature and in the English group watching the original version of Casablanca.”

“these results, which have subsequently been supported by those obtained in Di Giovanni and Romero (2018) with Italian participants, point to the potential existence of a dubbing effect, an unconscious eye movement strategy performed by dubbing viewers to avoid looking at mouths in dubbing, which prevails over the natural way in which they watch original films and real-life scenes, and which arguably allows them to suspend disbelief and be transported into the fictional world. Although not conscious, this mechanism seems to be activated only with dubbed films and is then turned off when watching an original film, where the viewing pattern is aligned with eye movements in real life.”

NOTAS

“It is worth noting that eye tracking can only detect the central vision obtained by the fovea (Slaghuis and Thompson 2003). Foveal vision allows us to obtain detailed information typically within six degrees of our field vision, that is, spanning five words in a row when reading printed text at ordinary size at about 50 centimeters from the eyes. Parafoveal or peripheral vision, which can span up to 120 degrees, is thus not detected by eye trackers.” Ora, amigo, isso muda toda a conclusão do estudo! É óbvio que as pessoas simplesmente olham para a face inteira das pessoas na tela!

“However, even though peripheral vision can be used to differentiate movement from stillness and even certain types of rhythms and contrast, it cannot help to distinguish colours, shapes or details (Wästlund et al. 2017).” HMM… O que você está dizendo é que NÃO existe visão periférica? Como conseguimos assistir em 16:9 gigantes?