THE ESSENTIAL VEDANTA: A New Source Book of Advaita Vedānta – Eliot Deutsch & Rohit Dalvi // Um esforço por compreender os ensinamentos éticos hindus e de crítica do cristianismo via herança da filosofia continental.

“We are concerned in short to understand Advaita Vedānta both in terms of cultural history and philosophy.”

“We have not included in this work any material from the neo-Vedānta that has developed in India in recent decades (e.g., Vivekananda, Aurobindo, Radhakrishnan) as the literature of this movement, having been written in English, is readily accessible.”

PART I.

BACKGROUND IN TRADITION: THE THREE DEPARTURES

“Vedānta means in the first place the ‘Conclusion of the Veda’ in the double sense that the Veda has come to an end here and that it has come to a conclusion. This final portion of the Veda comprises principally the Upanishads, which form the last tier in the monument we call the Veda.

In the second place, Vedānta is an abbreviation of Vedāntamīmāmsā, or the ‘Enquiry into the Vedānta’—the name of the most interesting, most influential, and most diverse of the philosophical traditions of Hindu India. Its very name implies a program: it is a tradition which intends to base itself on the Vedānta in the primary sense, the Upanishads.”

“Classical Vedānta recognizes 3 ‘points of departure’ (prasthānatraya) for its philosophy; that is to say that all Vedānta true to its name accepts the authority of three texts, or sets of texts, which authenticate its conclusions. There is, then, first the set of Upanishadic texts; further, the text of the Bhagavadgītā; and finally, the text of the Brahmasūtras. Each adds a new dimension to the others.

It is clear, therefore, that any investigation into Vedānta must be preceded by an enquiry into its traditional sources. These sources may appear to be difficult and at times indeed abstruse; but they set up the problems to which Vedānta addresses itself and which it intends to resolve through its commentaries on these sources.

The basic works of the founders of the different Vedānta schools present themselves as commentaries on the traditional sources; while most of their works are original to a high degree and often seem to owe little more to the admitted sources than an inspiration, nevertheless the philosophers themselves in all honesty present themselves as commentators only.”

“We shall briefly sketch the 3 Departures under the headings of ‘Revelation’, ‘Recollection’, and ‘System.’”

1.1 REVELATION

“If we are to form a proper understanding of the meaning and scope of ‘Revelation’, we do well to forget at once the implications of the term in the Mediterranean religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Strictly speaking, ‘revelation’ is a misnomer, since ultimately there is no revealer. The Sanskrit term for it is śruti, literally ‘the hearing’, which means an erudition acquired by listening to the instruction of a teacher. This instruction itself had been transmitted to the teacher through an uninterrupted series of teachers that stretches to the beginning of creation.

Revelation, therefore, is by no means God’s word—because, paradoxically, if it were to derive from a divine person, its credibility would be impugned. (…) It is axiomatic that revelation is infallible, and this infallibility can be defended only if it is authorless.”

“For some of the Mīmāmsā (or orthodox, exegetical) thinkers who have addressed themselves to this problem, the world is beginningless and the assumption of a creator is both problematic and unnecessary.” A resposta está tão no presente quanto em qualquer passado. Implicações para a filosofia continental: Dasein.

“And even if a beginning of the world is assumed, as in later Hindu thought when it is held that the universe goes through a pulsating rhythm of origination, existence, and dissolution, it is also held that at the dawn of a new world the revelation reappears to the vision of the seers, who once more begin the transmission.”

“Revelation (…) lays down first and foremost what is our dharma, our duty. This duty is more precisely defined as a set of acts which either must be done continuously (nitya), or occasionally (naimittika), or to satisfy a specific wish (kāmya).”

“Orthodox consensus recognizes 3 fundamental means of knowledge (…) Of these means (pramānas), (1) sensory perception (pratyaksa) holds the first place, for it is through perception that the world is evident to us. Built upon perception is (2) inference (anumāna), in which a present perception combines with a series of past perceptions to offer us a conclusion about a fact which is not perceptibly evident. (…) (3) Revelation is authoritative only about matters to which neither perception nor inference gives us access”

“the orthodox Exegetes would reject most of the Bible as Revelation: most of it they would classify as itihāsa or purāna, ‘stories about things past’, describing events which were accessible to perception and hence require only the authority of perception; but, for example, the chapters dealing with the Law in Deuteronomy would be considered Revelation in the true sense, since here rules are laid down and results are set forth which escape human perception and inference.

Led by this principle, the Exegetes classified Revelation under 3 basic rubrics, ‘injunction’ (vidhi or niyoga, including prohibition or nisedha), ‘discussion’ (arthavāda), and ‘spell’ (mantra). Spells comprise the mass of formulae, metric or in prose, which were employed at the execution of the rites. Discussion comprises all the texts which describe, glorify, or condemn matters pertaining to rites. Injunction comprises all the statements, direct or indirect, which lay down that certain rites or acts must be done or must not be done.

The stock example is svargakāmo jyotistomena yajeta, ‘he who wishes for heaven should sacrifice with the soma sacrifice’. It is in such statements that the authority of Revelation finally resides. It enjoins an action (offering up a sacrifice), the nature of which escapes human invention, for a purpose (heaven) whose existence neither perception nor inference could have acknowledged, upon a person (the sacrificer) who stands qualified for this action on the basis of the injunction. Declarations [mantras?] which accompany the description of the sacrifice, e.g., ‘the sacrificial pole is the sun’, while strictly speaking untrue and carrying no authority, have a derivative authority insofar as they are subsidiary to and supportive of the injunction, and may be condemnatory or laudatory of facts connected with the rite laid down in the injunction (e.g., the sacrificial pole is compared to the sun in a laudatory fashion for its central function at the rite). The spells accompanying the festive celebration of the rite have their secondary, even tertiary, significance only within the context of the rite laid down in the injunction.”

“the Four Vedas as we call them, the Veda of the hymns (rk), the formulae (yajus), the chants (sāma), and the incantations (atharva), are almost entirely under the rubric of ‘spell’. The large disquisitions of the Brāhmanas are almost entirely ‘discussion’, except for the scattered injunctions in them; and the same largely holds for the 3rd layer of texts, the Āranyakas. Generally speaking, Vedānta will go along with this view.

It is, however, with the last layer of text (the Vedānta or the Upanisads) that Exegetes and Vedāntins come to a parting of ways. For the Exegetes the Upanisads are in no way an exception to the rules that govern the Revelation as a whole. Nothing much is enjoined in them nor do they embody marked spells. In fact, they are fundamentally ‘discussion’, specifically discussion of the self; and such discussion certainly has a place in the exegetical scheme of things, for this self is none other than the personal agent of the rites and this agent no doubt deserves as much discussion as, say, the sacrificial pole.

Basically therefore the Exegetes find the Revelation solely, and fully, authoritative when it lays down the Law on what actions have to be undertaken by what persons under what circumstances for which purposes. Vedānta accepts this, but only for that portion of Revelation which bears on ritual acts, the karmakānda. But to relegate the portion dealing with knowledge, the jñānakānda, to the same ritual context is unacceptable.”

“The consensus of the Vedānta is that in the Upanisads significant and authoritative statements are made concerning the nature of Brahman. § From the foregoing it will have become clear that very little of the Revelation literature preceding the Upanisads was of systematic interest

to the Vedāntins. For example, Śamkara quotes less than 20 verses from the entire Rgveda in his commentary on the Brahmasūtras, about 14 lines from the largest Brāhmana of them all, the Śatapatha Brāhmana, but no less than 34 verses from the Mundaka Upanisad, a fairly minor and short Upanisad.”

Rgveda X, 129

“Among the hymns of the Rgveda that are clearly philosophical both in character and influence none is more important than the Hymn of Creation. This hymn exhibits a clear monistic or non-dualistic concern, an account of creation that gives special attention to the role of desire, and a kind of skeptical or agnostic attitude concerning man’s (and even god’s) knowledge of creation. The following translation is from A.A. Macdonell, n.d.

Non-being then existed not nor being:

There was no air, nor sky that is beyond it.

What was concealed? Wherein? In whose protection?

And was there deep unfathomable water?

Death then existed not nor life immortal;

Of neither night nor day was any token.

By its inherent force the One breathed windless:

No other thing than that beyond existed.

Darkness there was at first by darkness hidden;

Without distinctive marks, this all was water.

That which, becoming, by the void was covered,

That One by force of heat came into being.

Desire entered the One in the beginning:

It was the earliest seed, of thought the product.

The sages searching in their hearts with wisdom,

Found out the bond of being in non-being.

Their ray extended light across the darkness:

But was the One above or was it under?

Creative force was there, and fertile power:

Below was energy, above was impulse.

Who knows for certain? Who shall here declare it?

Whence was it born, and whence came this creation?

The gods were born after this world’s creation:

Then who can know from whence it has arisen?

None knoweth whence creation has arisen;

And whether he has or has not produced it:

He who surveys it in the highest heaven,

He only knows, or haply he may know not.”

Chāndogya Upanisad VI

“This text portion, which comprises the entire sixth chapter of the Chāndogya Upanisad, is no doubt the most influential of the entire corpus of the Upanisads.”

“It lays down for Vedānta that creation is not ex nihilo, that the phenomenal world is produced out of a preexistent cause. This cause is the substantial or material cause (upādāna), which, by the example of the clay and its clay products (section 1), provides the authority for the tenet that the phenomenal world is non-different from its cause.” “the Existent (sat) referred to is no other than Brahman” “Thus this text presents us with the basic problem of Vedānta, the relation between the plural, complex, changing phenomenal world and the Brahman in which it substantially subsists.”

“It teaches that <You are That,> and thus, for Vedānta, lays down that there is an identity (however to be understood)¹ between the Brahman and the individual self. This makes the text one of the <great statements> (mahāvākya) for Śamkara, who reads in it the ultimate denial of any difference between the consciousness of the individual self and the consciousness that is Brahman.”

¹ “whether this non-difference signifies a complete non-dualism (Śamkara), a difference-non-difference (Bhāskara),a or a non-difference in a differentiated supreme (Rāmānuja).”b

a Dialética hegeliana. Este é o famoso matemático/lógico a que somos traumaticamente introduzidos na quinta série.

b Essencialmente o que se pergunta é uma coisa só: Eu também sou Brahma. Mas o que isso quer dizer de fato (e esta será a maior preocupação de todos os textos sagrados)?

Em suma, a criação é um processo voluntário e deliberado. O Cristianismo particularmente apresenta uma criação ex nihilo, ao mesmo tempo em que acusa o credo hindu de recair na mesma “falha” (que eles o considerem de voz própria uma falha já diz muita coisa).

“The text is presented in a new translation by J.A.B. van Buitenen. It differs in many instances from previous translations which, he believes, have been unduly influenced by the interpretation of Śamkara. For example in section 4, the repeated <fireness has departed from fire,> <sunness has departed from sun,> <moonness has departed from moon,> <lightningness has departed from lightning> do not signify that there is in reality no fire, sun, moon, and lightning, but rather that these 4 entities, which previously had been considered irreducible principles, can be further analyzed into compounds of the Three Colors or Elements that Uddālaka sets up.”

“Since a source book should avoid presenting sources in a controversial manner, the reader is urged to consult, e.g., Franklin Edgerton’s translation in Beginnings of Indian Philosophy, Hume’s in Thirteen Principal Upanisads, Radhakrishnan’s in The Principal Upanisads, to quote the more accessible ones, for further reference.”

“At the age of 12 he went to a teacher and after having studied all the Vedas, he returned at the age of 24, haughty, proud of his learning and conceited.

…

‘Śvetaketu, now that you are so haughty, proud of your learning and conceited, did you chance to ask for that Instruction by which the unrevealed becomes revealed, the unthought thought, the unknown known?’

…

‘…Creating is seizing with Speech, the Name is Satyam, namely clay.

…

Creating is seizing with Speech, the Name is Satyam, namely copper.

…

Creating is seizing with Speech, the Name is Satyam, namely iron.’

‘Certainly my honorable teachers did not know this. For if they had known, how could they have failed to tell me? Sir, you yourself must tell me!’

‘So I will, my son,’ he said.

…

‘The Existent was here in the beginning, my son, alone and without a second. On this there are some who say, The Nonexistent was here in the beginning, alone and without a second. From that Nonexistent sprang the Existent.’

…

‘How could what exists spring from what does not exist? On the contrary, my son, the Existent was here in the beginning, alone and without a second.’

…

‘I may be much, let me multiply.’

…

‘Of these beings indeed there are 3 ways of being born: it is born from an egg, it is born from a live being, it is born from a plant.’

…

[3:4 PRINCÍPIO DA REALIDADE QUATERNÁRIA – O UNO QUE TRIPLICA E AINDA SE CONSERVA (3 + 1), SENDO O TRIPLO UNO AO MESMO TEMPO – FILOSOFIA CONTINENTAL OCIDENTAL: AS 3 DIMENSÕES + A VONTADE, INVISÍVEL, REGEDORA.]

‘I will make each one of them triple. This deity created separate names-and-forms by entering entirely into these 3 deities with the living soul.’

…

‘The red color of fire is the Color of Fire, the white that of Water, the black that of Food. Thus fireness has departed from fire. Creating is seizing with Speech, the Name is Satyam, namely the Three Colors.

The red color of the sun is the Color of Fire, the white that of Water, the black that of Food. Thus sunness has departed from the sun. Creating is seizing with Speech, the Name is Satyam, namely the Three Colors.

The red color of the moon is the Color of Fire, the white that of Water, the black that of Food. Thus moonness has departed from the moon. Creating is seizing with Speech, the Name is Satyam, namely the Three Colors.

The red color of lightning is the Color of Fire, the white that of Water, the black that of Food. Thus lightningness has departed from lightning. Creating is seizing with Speech, the Name is Satyam, namely the Three Colors.’

[A luz é diferente: dela emana o Único, não importa o objeto emissor, não importa o objeto refletor. Fogo, sol, lua, relâmpago. Sangue é a cor da vida, acorde fundamental do homem.]

…

‘Now no one can quote us anything that is unrevealed, unthought, unknown,’

…

‘If something was more or less red, they knew it for the Color of Fire; if it was more or less white, they knew it for the Color of Water; if it was more or less black, they knew it for the Color of Food.

[calor/energia, líquido e vida em si]

If something was not quite known, they knew it for a combination of these 3 deities. Now learn from me, my son, how these 3 deities each become triple on reaching the person.

The food that is eaten is divided into 3: the most solid element becomes excrement, the middle one flesh, the finest one mind.

The water that is drunk is divided into 3: the most solid element becomes urine, the middle one blood, the finest one breath.

The fire that is consumed is divided into 3: the most solid element becomes bone, the middle one marrow, the finest one speech.’

[Fez-se vento, palavra e consciência.]

…

‘Man consists of 16 parts, my son. Do not eat for 15 days. Drink water as you please. The breath will not be destroyed if one drinks, as it consists in Water.’

He did not eat for 15 days. Then he came back to him. ‘What should I say, sir?’

‘Lines from the Rgveda, the Yajurveda and the Sāmaveda, my son.’

‘They do not come back to me, sir.’

…

‘Eat. Afterwards you will learn from me.’

…

‘Just as one ember, the size of a firefly, that remains of a big piled-up fire will blaze up when it is stacked with straw and the fire will burn high thereafter with this ember, so, my son, one of your 16 parts remained. It was stacked with food and it blazed forth, and with it you now remember the Vedas. For the mind consists in Food, my son, the breath in Water, speech in Fire.’ This he learnt from him, from him.

…

‘When a man literally sleeps, then he has merged with Existent. … that is why they say that he sleeps. For he has entered the self.’

…

‘the breath is the perch [residência] of the mind, my son.’

…

‘water is food leader’

…

‘fire is water leader’

…

‘the fire is root’

…

‘All creatures are rooted in the Existent.’

…

‘Of this man when he dies, my son, the speech merges in the breath, the breath in the Fire, the Fire in the supreme deity. That indeed is the very fineness by which all this is ensouled, it is the true one, it is the soul. YOU ARE THAT, Śvetaketu.’

…

‘Just as the bees prepare honey by collecting the juices of all manner of trees and bring the juice to one unity, and just as the juices no longer distinctly know that the one hails from this tree, the other from that one, likewise, my son, when all these creatures have merged with the Existent they do not know, realizing only that they have merged with the Existent.’

…

‘The rivers of the east, my son, flow eastward, the rivers of the west flow westward. From ocean they merge into ocean, it becomes the same ocean. Just as they then no longer know that they are this river or that one, just so all these creatures, my son, know no more, realizing only when having come to the Existent that they have come to the Existent. Whatever they are here on earth, tiger, lion, wolf, boar, worm, fly, gnat or mosquito, they become that.’

…

‘If a man would strike this big tree at the root, my son, it would bleed but stay alive. If he struck it at the middle, it would bleed but stay alive. If he struck it at the top, it would bleed but stay alive. Being entirely permeated by the living soul, it stands there happily drinking its food.

If this life leaves one branch, it withers. If it leaves another branch, it withers. If it leaves a third branch, it withers. If it leaves the whole tree, the whole tree withers. Know that it is in this same way, my son, that this very body dies when deserted by this life, but this life itself does not die.’

[O receptáculo passageiro morre, mas a vida mesma não.]

…

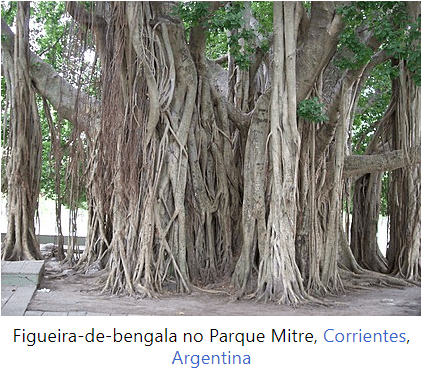

‘Bring me a banyan fruit.’

‘Here it is, sir.’

‘Split it.’

‘It is split, sir.’

‘What do you see inside it?’

‘A number of rather fine seeds, sir.’

‘Well, split one of them.’

‘It is split, sir.’

‘What do you see inside it?’

‘Nothing, sir.’

…

‘This very fineness that you no longer can make out, it is by virtue of this fineness that this banyan tree stands so big. Believe me, my son. It is this very fineness which ensouls all this world, it is the true one, it is the soul….’

…

‘Throw this salt in the water, and sit with me on the morrow.’

…

‘Well, bring me the salt that you threw in the water last night.’

He looked for it, but could not find it as it was dissolved.

‘Well, taste the water on this side.—How does it taste?’

‘Salty.’

‘Taste it in the middle.—How does it taste?’

‘Salty.’

‘Taste it at the other end.—How does it taste?’

‘Salty.’

‘Take a mouthful and sit with me.’ …

‘It is always the same.’

… ‘You cannot make out what exists in it, yet it is there.…’

…

‘Suppose they brought a man from the Gandhāra country, blindfolded, and let him loose in an uninhabited place beyond. The man, brought out and let loose with his blindfold on, would be turned around, to the east, north, west, and south.

Then someone would take off his blindfold and tell him, Gandhāra is that way, go that way. Being a wise man and clever, he would ask his way from village to village and thus reach Gandhāra. Thus in this world a man who has a teacher knows from him, So long will it take until I am free, then I shall reach it.’

…

‘When a man is dying, his relatives crowd around him: Do you recognize me? Do you recognize me? As long as his speech has not merged in his mind, [become oneself again – somos o desdobramento e o desbordamento] his mind in his breath, his breath in Fire, and Fire in the supreme deity, he does recognize.

But when his speech has merged in the mind, the mind in the breath, the breath in Fire, and Fire in the supreme deity, he no longer recognizes.…’

…

‘They bring in a man with his hands tied, my son: He has stolen, he has committed a robbery. Heat the ax for him! If he is the criminal, he will make himself untrue. His protests being untrue, and covering himself with untruth, he seizes the heated ax. He is burnt, and then killed.

“If he is not the criminal, he makes himself true by this very fact. His protests being true, and covering himself with truth, he seizes the heated ax. He is not burnt, and then set free.’ [o conceito de ser libertado deveria ser o de ser queimado e assassinado]

…

This he knew from him, from him.”

(Este capítulo está numerado em 16 partes.)

Chāndogya Upanisad V, 3-10

“Here Śvetaketu, almost always the incompletely instructed pupil, complains to his father that he is unable to answer the riddles posed by a baron (ksatriya). This text, along with one closely related in the Brhadāranyaka Upanisad, presents the fullest account of the doctrine of transmigration, which on the whole is rather understated in the Upanisads.”

“The text is further remarkable in that it presents this doctrine as special knowledge of the ksatriya class. This has given rise to the hypothesis that there was a lively ambience of philosophy among the barons from which the brahmins were excluded.”

“Śvetaketu, the grandson of Aruna, went to the assembly of the Pañcālas. Pravāhana Jaivali said to him, ‘Boy, has your father instructed you?’

‘He has, sir.’

‘Then do you know where the creatures go from here?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Do you know the bifurcation of the two paths, the Way of the Gods and the Way of the Ancestors?’ [paralelo com Parmênides]

‘No, sir.’

‘Do you know why the world beyond does not fill up?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Do you know how the water in the 5th oblation becomes known as man?’

‘Not at all, sir.’

‘Then how do you call yourself instructed? How could one call oneself instructed if he does not know the answers?’

…

‘To be sure, your reverence told me, without having instructed me, that you had instructed me! Five questions did that accursed baron ask me, and I could not resolve a single one of them!’

‘The way you have stated them, my son, I do not know any one of them. If I had known the answers, why would I not have told you?’

…

‘Keep your human wealth, king! Relate to me the discourse which you mentioned before the boy!’

The king was cornered. He ordered him, ‘Stay a while.’ He said, ‘This wisdom, as you state it to me, Gautama, has never before you gone to the brahmins. That is why the rule in all the worlds belongs to the baronage.’

…

‘The world beyond, Gautama, is a fire. Of it the sun is the kindling, the rays the smoke, the glow the day, the embers the moon, the sparks the constellations.

In this fire the gods offer up faith; from the oblation springs King Soma.

The monsoon, [clima de chuvas intermitentes de verão – implica no firmamento, abaixo apenas da morada ígnea dos deuses] Gautama, is a fire. Of it the wind is the kindling, the cloud the smoke, the lightning the glow, the thunderbolt the embers, the hail stones the sparks.

In this fire the gods offer up King Soma. From this oblation springs the rain.

The earth, Gautama, is a fire. Of it the year is the kindling, space the smoke, night the glow, the compass points the embers, the intermediate points the sparks.

In this fire the gods offer up the rain. From this oblation springs food.

Man, Gautama, is a fire. Of him speech [falo] is the kindling, breath the smoke, the tongue the glow, the eye the embers, the ear the sparks.

In this fire the gods offer up food. From this oblation springs the seed.

Woman, Gautama, is a fire. Of her the womb is the kindling, the proposition the smoke, the vagina the glow, intercourse the embers, pleasure the sparks.

In this fire the gods offer up the seed. From this oblation springs the child.

Thus in the 5th oblation water becomes known as man. The embryo, enveloped by its membrane, lies inside for 10 months, or however long, then it is born.

Once born he lives for as long as he has life. When he has died his appointed death, people carry him from here to the fire, from which he had come forth and was born.

They who know it thus and in the forest devote themselves to faith and austerity, they go into the fire’s glow, from the glow to day, from day to the fortnight of waxing moon, and from that fortnight to the 6 months when the sun goes the northern course. From these months to the year, from the year to the sun, from the sun to the moon, from the moon to lightning. [?] There is a person who is not human; he conducts them to Brahman. This is the Way of the Gods as described. [Faetonte-Aqueronte-Caronte-Carente-Cura-do-ente…]

Now those who in the village devote themselves to rites and charity, they go into the fire’s smoke, from the smoke to night, from night to the other fortnight, from the other fortnight to the 6 months when the sun goes the southern course. They do not reach the year.

From the months they go to the world of the ancestors, from that world to space, from space to the moon: he is the King Soma, it is the food of the gods, the gods eat it.

There they stay out the remainder, then they return by the same way, namely to space, from space to wind. Having become wind, they become smoke. Having become smoke, they become mist. [zzz]

Having become mist, they become the cloud, and having become the cloud, they rain forth. They are born on earth as barley and rice, herbs and trees. From thence escape is indeed difficult. If a person eats that food and then ejaculates his semen, then one becomes once more. [um brâmane é um repetente]

They who in this world [forest or city] have been of pleasant deeds, the expectation is that they attain to pleasant wombs, of a brahmin, or a baron, or a clansman. But if they have been of putrid deeds, the expectation is that they attain to putrid wombs, of a dog, or a swine, or an outcaste.

[Essa é uma versão pobre e a-filosófica da doutrina da transmigração.]

But by neither of these paths go the lowly creatures that again and again come back. [the third way is a no-way] That is the third level, that of: Be Born! Die! Therefore the world beyond does not fill up. Hence one should watch out. There is this verse:

The thief of gold, the drinker of wine,

The corruptor of his teacher’s bed, a brahmin-killer,

Those four fall, and so the fifth who consorts with them.

If one does know these 5 fires, then one is not smeared with evil, even though consorting with them. Clean, pure, and of auspicious domain becomes he who knows it thus, who knows it thus.’” A salvação do brâmane me parece assaz fácil!

Taittirīya Upanisad II, 1–8

“It outlines, even though in primitive terms, a hierarchy of the person—5 ‘sheaths’ (kośa) of increasing interiority.”

“This is his head, this his right side, this his other side, this his trunk, this his tail, his foundation.” O homem tem 5 partes físicas, e uma delas é a cauda?!

“2. From food arise the creatures, whichsoever live on earth, and through food alone do they live, and to it they return in the end. Of all elements, food indeed is the best, hence it is called the best medicine. They forsooth attain to all food who contemplate on Brahman as food. From food are the creatures born, and once born they grow through food. It is eaten and eats the creatures, hence it is called food.”

“The prāna is its head, the vyāna its right side, the apāna its left side, space the trunk, earth its tail, its foundation.” O rabo do homem é a terra, é o chão, é o solo, a base. Ele não pode voar (seu rabo não regride).

4. “Faith is its head, order the right side, truth the other side, discipline the trunk, mahas the tail, the foundation.”

5. “Happiness is its head, joy its right side, rapture its other side, bliss its trunk, Brahman its tail, its foundation.”

“6. Nonexistent becomes he when he knows Brahman as nonexistent. When he knows that Brahman exists, they know him by that to exist.” Interessante.

“7. In the beginning the Nonexistent was here, from it was born the existent. It made itself into a self, that is why it is called well-made. That which is well-made is the sap [seiva, vida]. For upon attaining to this sap one becomes blissful. For who would breathe in and breathe out if there were no bliss in his space?”

O oitavo parágrafo (críptico): Brahma é a Morte?

Katha Upanisad

“[this book] sets forth a state of bliss to be had through an intense concentration of consciousness and, finally, a surpassing state of joy and liberation.

The text, given here in its entirety, is a translation of Patrick Olivelle”

“So he asked his father: ‘Father, to whom will you give me?’ He repeated it for a second time, and again for a third time. His father yelled at him: ‘I’ll give you to Death!’”

“A mortal man ripens like grain,

And like grain he is born again.”

“You, O Death are studying,

the fire altar that leads to heaven;

Explain that to me, a man who has faith;

People who are in heaven enjoy the immortal state—

It is this I choose with my second wish.”

“(Death)

I shall explain to you—

and heed this teaching of mine, O Naciketas,

you who understands the fire altar that leads

to heaven, to the attainment of an endless world,

and is its very foundation.

Know that it lies hidden, in the Cave of the heart.”

“Choose your third wish, O Naciketas.

There is this doubt about a man who is dead.

‘He exists,’ say some, others, ‘He exists not.’

I want to know this, so please teach me.

This is the third of my wishes.

(Death)

As to this even the gods of old had doubts,

for it’s hard to understand, it’s a subtle doctrine.

Make, Naciketas, another wish.

Do not press me! Release me from this.

(Naciketas)

As to this, we’re told, even the gods had doubts,

and you say, O Death, it’s hard to understand.

But another like you I can’t find to explain it;

and there is no other wish that is equal to it.

(Death)

Choose sons and grandsons who’d live a hundred years!

Plenty of livestock and elephants, horses and gold!

Choose as your domain a wide expanse of earth!

And you yourself live as many autumns as you wish!”

Resposta fraca

“And if you would think this an equal wish—

You may choose wealth together with a long life;

Achieve prominence, Naciketas, in this wide world;

And I will make you enjoy your desires at will.

You may ask freely for all those desires,

hard to obtain in this mortal world;

Look at these lovely girls, with chariots and lutes,

girls of this sort are unobtainable by men—

I’ll give them to you; you’ll have them wait on you;

But about death don’t ask me, Naciketas.”

Outrossim, a sedução do diabo no deserto (Novo Testamento).

“(Naciketas)

Since the passing days of a mortal, O Death,

sap here the energy of all the senses;

And even a full life is but a trifle;

So keep your horses, your songs and dances!

*

With wealth you cannot make a man content;

Will we get to keep wealth, when we have seen you?

And we get to live only as long as you allow!

So, this alone is the wish that I’d like to choose.

*

What mortal man with insight,

who has met those that do not die or grow old,¹

himself growing old in this wretched and lowly place,

looking at its beauties, its pleasures and joys,

would delight in a long life?”

¹ Seria uma interessante parábola, se existissem tais deuses ou vampiros! Ou, conforme veremos adiante, Naciketas fala dos sábios, em sentido puramente alegórico.

“The point on which they have great doubts—

what happens at that great transit—

tell me that, O Death!

This is my wish, probing the mystery deep,

Naciketas wishes for nothing

other than that.”

Didn’t anybody say that to you: Careful what you wish?

UMA CRÔNICA DE DOIS IRMÃOS:

“(Death)

The good is one thing, the gratifying [prazeres] is another;

their goals are different, both bind a man.

Good things await him who picks the good;

By choosing the gratifying, one misses one’s goal.

*

Both the good and the gratifying

present themselves to a man;

The wise assess them, note their difference;

And choose the good over the gratifying;

But the fool chooses the gratifying

rather than what is beneficial.

*

…

This disk of gold, where many a man founders,

You have not accepted as a thing of wealth.

*

Far apart and widely different are these two:

Ignorance [prazer] and what’s known as knowledge. [o bem]

I take Naciketas as one yearning for knowledge;

The many desires do not confound you.

*

Wallowing in ignorance, but calling themselves wise,

Thinking themselves learned the fools go around,

staggering about like a group of blind men,

led by a blind man who is himself blind. [um homem cego é mesmo cego!]

*

This transit lies hidden from a careless fool,

who is deluded by the delusion of wealth.

Thinking ‘This is the world; there is no other’,

he falls into my power again and again.”

Creio que ninguém ainda entendeu o verdadeiro sentido do texto. Em vermelho: o hedonista ou materialista pensa “não há outro mundo, só este, carpe diem, etc.”. Mas é só este quem morre. O outro mundo é neste mundo mesmo, invisível, habitado somente pelos sábios. Eles nunca morrem. Apud Sócrates-Platão-…

“Many do not get to hear of that transit;

and even when they hear,

many don’t comprehend it.

Rare is the man who teaches it,

Lucky is the man who grasps it;

Rare is the man who knows it,

Lucky is the man who is taught it.”

Mais más concepções: não se ouve a verdade muito amiúde; quando se a escuta, se a ignora como se ela nunca fôra proferida. Isto é Zaratustra livro I, cena da praça e do mercado. Não é raro o homem que ensina a sabedoria: tantos quantos são estes professores (os sábios, a.k.a. virtuosos), uma vez na vida eles acreditam poder ensinar – esse é seu erro; a virtude não pode ser ensinada. Portanto, só quem sábio se torna, sábio já era. Torna-te aquilo que tu és. Raro é o homem assim constituído. Sortudo é quem nasceu nessa condição, pois só assim “lhe foi ensinado” o conteúdo: por si mesmo.

“Though one may think a lot, it is difficult to grasp,

when it is taught by an inferior man.

Yet one cannot gain access to it,

unless someone teaches it.

For it is smaller than the size of the atom,

a thing beyond the realm of reason.”

Não existe o guru. Quantas vezes ter-se-á de dizê-lo? Quantos murros em ponta de faca? O final, porém, é adequado: a vontade ou Idéia é menor que qualquer pedaço de matéria, o que o século XX chama de partículas sub-atômicas fundamentais. Não é deste mundo, é do outro mundo vivenciado neste mundo pelos privilegiados de nascença (se há algo do mito brâmane que sobrevive é esse fatalismo: ou se nasce sábio e bom, ou se nasce ignorante e mau). E é vontade ou Idéia, esses nomes “estranhos”, embora familiares no léxico (mas quase nunca sabem seu significado!), porque não é razão, está além da razão. Quem disse que o sábio o é em virtude da razão?! Quem disse que a Idéia de Platão ou a virtude são alcançadas pela inteligência? Somente pelo instinto, pela inclinação natural em vê-las e senti-las, em sê-las (com isso que chamam de Brahma).

“One can’t grasp this notion by argumentation;¹

Yet it’s easy to grasp when taught by another.²

You’re truly steadfast dear boy,

you have grasped it!

Would that we have, Naciketas,

One like you to question us.”²

¹ A dialética esvaziada de um Aristóteles, o Racional.

² O outro é sempre si mesmo, sempre a ressalva em relação aos textos sagrados hindus, que ainda não tinham a consciência da origem da sabedoria, talvez a única vantagem oferecida pela filosofia ocidental sobre o maior trabalho, a maior sabedoria, embora inconsciente, trazida pelo Oriente, e que hibernou por tanto tempo, entre nós e até eles próprios, os professores do Veda! Us também não existe. Quem formula as perguntas e também as respostas naquele que não pode ser igualado (Platão)? Ele mesmo. A Morte neste Upanishad não é uma fraude, um espírito trickster, mas, pelo contrário, o alter ego de Naciketas: este é um diálogo, a maiêutica do sábio. Quem preside é ele mesmo, mediante suas reminiscências. Outra frase célebre: Dai a César o que é de César, significa: dai a este mundo o que quer este mundo: a humildade, a labuta, um mal-disfarçado senso de superioridade (porque os tolos, em sua maior parte, crêem na sua modéstia e na sua inferioridade, não se pode usar a sabedoria para angariar vantagens no jogo temporal). Assim quitais vossas dívidas com eles. Nosso eterno sofrimento, a eterna convivência com os eternos anões. O preço de nosso paraíso, no outro mundo que é aqui, sem testemunhas senão nossos poucos iguais. Jesus Cristo, o incompreendido. Ao mesmo tempo que não iniciou, o Juízo já terminou e está acontecendo. Acontece. Todo ele é a existência. A existência é uma criação escatológica.

“What you call a treasure, I know to be transient;”

tesouro transcendental

“Therefore I have built the fire altar of Naciketas,

and by things eternal I have gained the eternal.”

Jogando minha alma na aposta eu consegui meu objetivo: a eternidade. O outro mundo neste mundo. O presente do presente, o único tempo real. A única felicidade tangível. Sem necessidade de nenhuma providência; pois já estava lá, sempre esteve.

“[Já não importa quem fala, é o Um e o Mesmo]

The primeval one who is hard to perceive,

wrapped in mystery hidden in the cave,¹

residing within the impenetrable depth—

Regarding him as god,² an insight

gained by inner contemplation,³

both sorrow and joy the wise abandon.”4

¹ E quem é que começa a vida preso à caverna, no mito (ou inclusive na historiografia “séria” – como se o mito não o fosse –: homem das cavernas)? O homem. Não é que o homem busque o sol que é a Iluminação ou instrumento necessário para iluminar aquilo que não se vê. Ou em outras palavras: aquilo que não se vê a descoberto é a si mesmo. O homem não se sabe homem, não sabe o que é, precisa do sol para entender que é o que tanto procurava. O mistério da vida é o mistério do homem diante do espelho. O eu, o maior enigma. O mundo dos homens, normalmente entendido como tão despido de significado quanto “o mundo de um deus desconhecido”, ou “de um deus que morreu”. O Mito da Caverna inverte a mitologia grega em geral: não estamos destinados a nos tornar sombras, mas somos sombras que eventualmente se incorporam e ganham volume, densidade, matéria, substância, cor, tangibilidade, vida.

² Na minha interpretação é o exato oposto: sem a companhia de ninguém, e deixado à própria sorte no fundo da caverna, em sua cela do Ser, o homem não pode atingir a hubris nem a auto-afirmação: divino é o estado mais difícil. O Um sem o Outro é prosaico.

³ Isso só pode ser exato depois da própria jornada, da odisséia, do retorno diferente ao mesmo lugar do princípio.

4 Como resultado inevitável da viagem exitosa. Quem tem o presente seria por definição feliz, como quer o hindu. Porém, em face do conhecimento da eternidade neste mundo (o outro mundo), sensações transitórias perdem o significado: o que é tristeza, o que é alegria sem contraste ou interrupção, sem-fim? Nada.

“When a mortal has heard it, understood it;

when he has drawn it out;

and grasped this subtle point of doctrine,

he rejoices, for he has found

something in which he could rejoice.

To him I consider my house

to be open, Naciketas.”

A liberação é saber que fora de todo o possível, fora do eterno presente, só fora, e só para quem está consciente do presente, no impossível (pois não existe esse fora), finalmente é concedido o direito de morrer. Não há transição. Só há transição na eternidade do presente e da ação. Mas o que é bênção para nós é maldição para quem tem medo da morte ou esperança eterna num outro mundo que não seja deste mundo. Eles já vivem neste outro mundo que desejam: eles são objetos, não são homens. O tempo corre para eles. Estão condenados a jamais morrer, porque para eles a vida é uma morte contínua.

Veja que o próprio compilador, ou tradutor, está confuso quanto à identidade de quem fala (como eu disse, não importa, é a mesma pessoa!):

“Seeking which people live student lives”

Buscando quais pessoas vivem vidas de estudante. O estudante dos Vedas é a figura perfeita dos Vedas. Não só dos Vedas: da existência mesma, das Idéias de Platão e da vontade de Nietzsche. O professor dos Vedas é só um artifício didático: ele é outro estudante, o daimon guia do bom caminho. Nunca cessamos de aprender, e de nos tornar mais sábios, mas não existe a Idéia do sábio: a idéia, a busca da sabedoria. A imagem perfeita. Tão perfeita que poderíamos nos perguntar se essa imagem não é a Idéia mesma. A imagem é a Idéia sobre a Idéia. A Idéia é a imagem da Idéia. A Idéia voltada para si mesma, a Idéia ao espelho. A sabedoria socrática. Esse é o infinito, pois não termina ou conclui, e é ao mesmo tempo um estado em perpétuo movimento. Um estado não-estado. Um movimento não-movimentado. A imagem das imagens.

A vontade, palavra do século XIX para o mesmo: deliberações sobre as entrelinhas de Platão, o contínuo debate da Idéia. Não menos perfeito que a Idéia, por não ser exatamente uma poesia da maiêutica (e quem disse que os aforismos não o são?), pois pressupõe a Idéia, já que não é debate estático. E é ao mesmo tempo estanque, porque não evadiu o bom caminho da Idéia. O invisível vivido pelo estudante (mestre).

OM é tudo, é vontade e é Idéia. Vibração contínua. Sempre há um ponto cego para o sábio, mas é ele que indica o bom caminho. Há sempre um mistério residual. Dádiva negativa do presente. Tê-lo em forma viva e depois querer tê-lo no mundo material para auferir vantagens é o mesmo que dele abdicar, cair na tentação sensualista da Morte na proposta ao estudante, do diabo a Jesus no deserto, da glória mundana. Uma confirmação empírica da Idéia desvaneceria a Idéia, descaracterizando seu ar incomunicável, indemonstrável, autorreferente e exclusivista, entrada para poucos e seletos. Ouvem-se as palavras Idéia, vontade e OM, mas, como disse a Morte acima, os habitantes deste mundo que esperam o outro mundo, sem saber que ele é este mesmo, não escutam. Escutam as palavras, mas não as compreendem. E escutar é compreender desde que o homem é homem. Escutar a mais bela melodia e não entender sua beleza? Quem não riria dessa “sabedoria” e deste pragmatismo dos tolos? Num mundo em que existem bem e mal, quem se dá bem, se dá mal. Assim poderíamos traduzir as palavras mais próximas a nosso tempo “muito além do bem e do mal”: o bem vigente não é o bem de Platão. Daí a razão da reviravolta que não é reviravolta (filosofia extrema de combate ao niilismo): contorceram tanto as palavras que já é necessário desfazer mal-entendidos a fim de se afirmar a mesma coisa de dois milênios atrás. O que já foi OM, e o que hoje não é entendido pelos exegetas hindus do OM, voltará a ser o mesmo OM originário, etc. Credo quia absurdum est?

“When, indeed, one knows this syllable,

He obtains his every wish.”

Sorte que nós não somos muito exigentes, e não pedimos desejos absurdos (com o perdão do trocadilho com o final do texto acima). Para nós tudo é possível, mas nem tudo é permitido (por nós mesmos), se pudermos incluir Dostoievsky na conversa, porque somos virtuosos e nossos desejos nada têm a ver com as fábulas dos adoentados morais, os sequiosos do outro mundo, materialistas incuráveis, a imaginar gênios que lhes concedam todo tipo de coisa inesgotável neste mundo; quando este mundo mesmo é esgotável (pelo menos para eles, pela forma como eles esperam saciar sua sede neste mundo, ainda contando com um outro!), que desejo logo não daria sede-de-mais aos pedintes? Esses mendicantes querem ganhar na mega-sena; os poucos que logram continuam sendo mendicantes, não há escapatória.

“And when one knows this support,

he rejoices in Brahman’s world.”

Brahman’s world = Brahman’s word

Outro mundo = Idéia, vontade, OM, presente eterno, vida do sábio

“The wise one—

he is not born, he does not die;

he has not come from anywhere;

He is the unborn and eternal, primeval and everlasting.

And he is not killed, when the body is killed.

(The dialogue between Naciketas and Death appears to end here.)”

Com minha ajuda, vocês certamente perceberam, o único mistério que subjaz é salutar para a compreensão do texto (o ponto cego do sábio). Então, modéstia à parte, não haveria nem mais que dizer – hora perfeita para encerrar o trabalho de parto (maiêutica do sábio). O Katha Upanishad não encerra aqui, porém; a narração objetiva, fora de qualquer diálogo, dá continuidade aos ensinamentos.

“If the killer thinks that he kills;

If the killed thinks that he is killed;

Both of them fail to understand.

He neither kills, nor is he killed.”

Caim não matou ninguém, apenas passou por tolo! Abel vive ainda. A natureza se feriu. Mas a natureza é imortal.

“Finer than the finest, larger than the largest,

is the self (Ātman)¹ that lies here hidden

in the heart of a living being.

Without desires and free from sorrow,

a man perceives by the creator’s grace

the grandeur of the self.”

¹ Provável etimologia de nossa palavra “alma”.

“Sitting down, he roams afar.

Lying down, he goes everywhere.¹

The god ceaselessly exulting—

Who, besides me, is able to know?”

¹ Uma das características do homem pós-moderno esvaziado de sentido é viajar (territorialmente falando mesmo) sempre que pode. À procura de algo que nunca encontra. Sempre em movimento – mas ironicamente sempre estagnado no mesmo lugar – tentando fugir inadequadamente de sua sombra. A viagem talvez seja uma característica indispensável do ser humano. Mas é possível atingir a Idéia, ou o presente eterno, nunca saindo de sua província, como é possível errar como o judeu amaldiçoado sem qualquer conseqüência. Ulisses seria um bom exemplo daquele que viaja e sai do lugar ao mesmo tempo. O turista do capitalismo tardio, no entanto, apenas repete tudo que sabe fazer enquanto erradicado na província, necessitando, não obstante, de novas vistas na janela e de uma gorda fatura no cartão de crédito – suas provas empíricas de que ele viveu. Que bebeu a mesma Heineken vendida em sua vizinhança além-mar…

“When he perceives this immense, all-pervading self,

as bodiless within bodies,

as stable within unstable beings—

A wise man ceases to grieve.

This self cannot be grasped,

by teachings or by intelligence,

or even by great learning.

Only the man he [the self] chooses can grasp him,

Whose body this self chooses as his own.”

Aqui, estranhamente, cai a exigência de um guru, de um mestre para o estudante do Veda, e a auto-eleição fatídica que comentei acima fica sancionada.

“Not a man who has not quit his evil ways;

Nor a man who is not calm or composed;

Nor even a man who is without a tranquil mind;

Could ever secure it by his mere wit.”

Nenhum religioso com segundas intenções. A “frieza” do sábio não é a frieza do erudito, tão reparada e criticada em nossos tempos. O sábio não é um erudito. Erudito é o filisteu da cultura de massas. Sócrates é o anti-filisteu clássico. A frieza do sábio não é a incapacidade de se comover, mas a impassibilidade com que entende a inevitabilidade do funcionamento do princípio da Teoria das Idéias, da Vontade de Potência, do Om. Queira ele ou não, queira seu ego ou não, estas são Verdades que ele compreende como verdadeiras, e por isso as aceita (com impassibilidade, sinônimo circunstancial de frieza). Doravante, este é o “eleito”, de mente tranqüila, calmo e composto. Não levemos essa exigência longe demais: quem duvida que um Sócrates apaixonado por Alcibíades, que um Nietzsche compondo os livros mais destrutivos da cultura filistéia, não cumprem o requisito desta compostura exigida? Um homem calmo não vive em fúria, mas pode demonstrar fúria – caso contrário não seria um homem que os hindus estariam procurando, mas um embotado qualquer, já incapaz da ira.

A conhecida mente fervilhante do artista tampouco é uma vedação: suscetível às mudanças no mundo e crente nesta vida (e não somente em outra) ele sabe se isolar em seu próprio espaço, concentrado (o outro mundo neste mundo), onde não tem igual (Rafaello Sanzio, Miquelângelo, etc.). Acima de tudo ele pode contemplar sua situação no mundo com a mesma objetividade de um deus, de um filósofo (como dito acima) e de alguém que está desinteressado de lucros mundanos (o que os demasiado espertos são incapazes de compreender – “se eu tivesse seu talento, eu faria acontecer, eu seria muito maior, estaria no topo do mundo” – se um pequeno ou medíocre tivesse o talento do talentoso, ele não “faria acontecer”, porque então ele não seria apenas um esperto sem sabedoria e não pensaria como pensa o sem-talentos).

“For whom the Brahmin and the Kshatriya

are both like a dish of boiled rice;

and death is like the sprinkled sauce;

Who truly knows where he is?”

Quem senão essa super-alma qualificada, este que incorporou Brahman, para ver até mesmo a casta superior indiana como um mero equivalente inanimado da classe dos guerreiros que não estudam os Vedas? A morte é um fenômeno como outro qualquer, um tempero que aumenta o gosto da comida. E quem anseia pelo outro mundo, o que quer com isso? Quer escapar da morte como quem desmaia e acorda bem-tratado pelos outros, anestesiado, fugido das pesadas implicações. Isso pelo menos quando ele está anormalmente convicto do outro mundo. Na maioria do tempo essas pessoas sentem a própria insignificância e banalidade, e tremem diante da simples palavra morte, como que pressentem que estão erradas e falam da boca para fora.

“They call these two ‘Shadow’ and ‘Light’,

The two who have entered—

the one into the cave of the heart,

the other into the highest region beyond,

both drinking the truth

in the world of rites rightly performed.”

A semelhança com o Mito da Caverna ou princípios como os recitados no mazdeísmo são óbvios.

“the imperishable, the highest Brahman,

the farthest shore

for those who wish to cross the danger.”

Decerto “as margens mais afastadas” não são um batismo ritual indiferente e vazio, “feito por fazer”, “herança dos costumes dos pais”, incompreendido em “seus mistérios”, realizado mais por medo que por qualquer outro sentimento, extremas unções, confissões e idas semanais à igreja, “para não ir para o inferno”. Não, essa odisséia não é para almas covardes que recorrem a atalhos inofensivos gravados nas pedras! Quem pode nos dizer, num país cristão, que já não estava impregnado de todas essas ridicularias desde que se entendeu por indivíduo? Porque, claro, podiam significar nada, mas há sempre um parente ou conhecido para dizer: “Antes de tal coisa, fazer 3 ave-marias e rezar 10 pais-nossos, se não funciona, ao menos não prejudica”. E assim assimilamos costumes que não podemos chamar de imbecis, porque só consideramos imbecil aquilo que podemos compreender, para avaliar; isso é menos que imbecil, é apenas um mistério herdado, automático, parte de nosso “arrumar a cama – escovar os dentes – etc.”. Não se pode jogar essas coisas fora sem substituí-las por algo melhor, dir-se-ia. O algo melhor é a verdade do conhecimento sagrado inconsciente hindu, que finalmente se tornou acessível a nós após séculos de filosofia ocidental. Não que possamos encarnar em qualquer outro a função de guru; o ritual de ascensão do ignoto herdado ao autoesclarecimento é sempre individualmente doloroso. Por isso os materialistas (hedonistas que se dizem espiritualistas!), seguros do outro mundo, são incapazes de efetuar essa transmutação.

“Know the self as a rider in a chariot,

and the body, as simply the chariot.

Know the intellect as the charioteer,

and the mind, as simply the reins.”

Uma imensa sabedoria condensada e destilada em 4 versos. Seria incapaz de enumerar a série de referências que enxergo em nosso saber ocidental ao ler somente as duas primeiras linhas: já a figura da carroça que ascende ao saber está presente na mitologia grega, na própria alusão ao deus-sol e seus servos. Hélio e Faetonte são pai e filho e contudo com o passar das gerações já se confundem num só ente. A carroça voadora deveria descrever a parábola do percurso do sol durante as 12 horas do dia (depois ele submerge e passa por debaixo dos oceanos, voltando ao leste). Mas Faetonte já é associado, a dado momento, à própria carruagem (o eu-controlado da figura poética acima). É ele, esse deus, na forma humana, qualquer que seja o nome, o único apto a conduzir a carroça sem se queimar (ou desviar do percurso correto). Desdobramentos, ainda helênicos, são perceptíveis na estória de Ícaro e seu malfadado vôo, nos escritos de Parmênides sobre o Um, no daimon de Sócrates (o self mais profundo, que conduz a ele próprio, o indivíduo histórico), que o orienta até em sonhos musicais na véspera de beber a cicuta (que ele não tema, aliás, o oposto: que ele celebre e comemore a vida no momento do estar-morrendo).

Essa voz interior passa, mais explícita ou menos explícita, pelos textos de todos os principais pensadores, até aterrissar nas investigações sobre o inconsciente, o novo nome para o daimon, nosso verdadeiro senhor. O que é um espírito-livre senão o escravo de si mesmo, ou melhor, aquele bom discípulo de si mesmo, que sabe dominar seus impulsos (ou assiste, enquanto impulsos cegos, a este domínio que vem aparentemente de fora, mas que é ele mesmo?), malgrado seu, e sabe ouvir os conselhos da sua verdadeira personalidade, desconhecida em seu todo até pela própria vida consciente do indivíduo? É o homem ético e abnegado que vê os filisteus de cima, meras manchas topográficas – esses filisteus que se julgam alpinistas de elite!

E ainda nem falei da metade final! O intelecto é o cocheiro. Que intelecto – depois que a duras penas aprendemos a desconfiar desse intelecto lato sensu desde Aristóteles até Kant? Decerto não é o intelecto cartesiano, o intelecto dos ceticistas dogmáticos, o intelecto dos Iluministas franceses, dos ateístas franceses – cristãos amargurados! –, o intelecto dos cabeças-de-vento do séc. XIX tão criticados por Nietzsche, a raça dos eruditos alemães! Não é o intelecto dos românticos que sucederam a Hegel, nem do próprio Hegel, o Aristóteles de nossa era. Mas um Goethe, que se equilibrou entre o Romantismo moderno e a serendipidade dos antigos, este está acima do gradiente que criticamos aqui! Dele que é o Fausto, já antigo e do folclore, mas que de sua pena é o mais célebre – mais um Jesus Cristo depenado por seu daimon errado. Mefistófeles é só um agente externo, a sociedade, o gênio da lâmpada dos que querem vencer na vida ganhando na mega-sena, não o demônio interior verdadeiro do sábio. E o ícone intelectual que ainda subsiste para nós na terceira década do séc. XXI – a fraude chamada Sigmund Freud, este compartimentador do inconsciente, que transformou num mapa ou num cubículo as forças incompreensíveis e virtualmente ilimitadas que nos regem – fariseu dos fariseus, pois como judeu esclarecido este homem sabia ser um filisteu, e continuou interpretando seu papel jocoso por maldade e ganho pessoal. O ápice do racionalismo deletério – o Descartes pós-descoberta explícita do daimon, pela primeira vez, desde Sócrates-Platão. E quantos séculos ele não terá retardado o estado das coisas? Não decerto para os poucos privilegiados, que vêem por trás da opacidade de sua pseudanálise, que enxergam por detrás dessas paredes (pontos cegos do indivíduo médio).

E as correntes de pensamento continuaram, na segunda metade do século XX, errando em pontos fundamentais, aprisionando esse self hindu. Marxistas desfiguradores do princípio maiêutico-dialético provisoriamente resgatado no XIX… Não faltava mais nada! A filosofia continental se fecha e vive de comentadores dos clássicos – talvez devêssemos comemorar. Já sabiam os últimos clássicos e já sabem os melhores comentadores que as próximas respostas úteis (úteis para nós, os anti-utilitários) devêm do Oriente, que, contrariando a projeção geológica de que os continentes africano e americano à deriva estariam se aproximando coisa de 10cm por ano, parece estar vindo a nosso encontro a galope… Portanto, para arrematar: o self hindu não é esse tipo de intelecto, só para deixar claro!

A mente simplesmente como os freios (rédeas). No sentido do poema a mente me parece apenas essa faculdade consciente dos eleitos que efetuam a boa jornada. A mente de Dédalo, o pai do imprudente Ícaro, a prudência altruísta, sem ambições solares, mas orgulhosa o suficiente para não recair em abismos.

“The senses, they say, are the horses,

and sense[d?] objects are the paths around them;

He who is linked to the body (Ātman), senses, and mind,

the wise proclaim as the one who enjoys.”

Quem é este que encontrou a eternidade verdadeira no único mundo possível senão “the one who enjoys”? Que momento há para gargalhar se não o presente? É verdade que a carruagem segue um percurso, mas não estamos atrás de nenhum destino particular. Como Ulisses, apesar das aparências, também não estava. Sobre cavalos, poderia até citar David Lynch, para quem, em Twin Peaks, o cavalo branco era o símbolo da morte próxima e também do vício, representado pelo hábito cocainômano da protagonista (uma protagonista que morre antes mesmo da série começar, eis uma quebra de normas!), nas duas primeiras temporadas apresentado de forma mais sugestiva, vaga, anedótica e espaçada. Na terceira temporada, no entanto, ganhamos também um poema sobre eles, os cavalos brancos, que nos brindam com muito mais associações, ou pelo menos com um termômetro para julgar as sugestões das primeiras temporadas: …The horse is the white in the eyes / and dark within, (mais alusão ao yin-yang) embora eu tenha omitido a primeira metade desta outra quadra (!), para não me estender com conteúdo não-relacionado aos Vedas (se é que existe um que não o seja). Novamente o contraste entre o preto e o branco, a luz e as trevas, elementos da odisséia, dialética que leva à verdade. Mas, cavalo branco ou não, alado ou não, essa charrete mitológica também tem o seu, ou os seus. Embora pareça pouco funcional, podemos dizer que são 5, os cinco cavalos são os 5 sentidos. Cinco cavalos que puxam servilmente a carruagem (você). Se a vacuidade emocional dos filisteus de nosso tempo é uma imagem de cortar o coração, (!) não nos enganemos: os sentidos, raiz dos sentimentos, não são desprezíveis para o sábio – acontece que aqui eles têm tratamento pejorativo, sem dúvida. Os cavalos ou os pégasos cavalgam ou flutuam por uma estrada ou por um arco imaginário no firmamento. A estrada do Um de Parmênides. A mente precisa subordinar os cavalos: o cavalo que olha é na verdade cego; o cavalo orelhudo é na verdade surdo; o cavalo frenético e suscetível tem na verdade a epiderme dormente; o cavalo narigudo não tem faro; e o cavalo linguarudo nem saberia se ingere capim ou torrões de açúcar. Sem uma coordenação estes cinco não são nada. E para quem sabe coordená-los, veja, eles são tudo! A via de acesso ao nosso outro mundo, que está aqui. Uma via insuficiente por si só, mas indispensável para a alma. Há quem ache que o presente são os próprios sentidos. Rematados tolos. Eles são a paradoxal via para o invisível, o que eles percebem são apenas os objetos e os contornos da estrada para o presente.

Acaba de me chamar a atenção o fato de que, consultando o dicionário, obtive que “obscuro” é um antônimo de presente. E acima se contrapôs a parte do olho que enxerga, a retina, à brancura dos cavalos, prenúncio de armadilha. Pois o que não seria essa fala na boca de um dos agentes do Black Lodge de David Lynch, nesse contexto de cavalgar por uma senda necessariamente perigosa, senão uma grave advertência sobre a mais próxima vizinhança entre o enxergar bem e o viver com um antolho nos olhos? E eu que achei que já havia secado este poço (esta é a hora dos fãs de Twin Peaks mais ligados rirem bastante)!

“When a man lacks understanding,

and his mind is never controlled;

His senses do not obey him,

as bad horses, a charioteer.”

Apenas um lembrete, já que tudo isso já foi bem-comentado e o trecho é simples: o cocheiro (o daimon, o Ātman) é muito mais que a mente. É evidente que esta não é apenas uma enumeração paralela de uma hierarquia dupla, é mais complexo que isso. [De modo simples: cocheiro/o inconsciente (guia maior) > homem/vida consciente/carruagem > mente/corpo/intelecção > cavalos/sentidos (guias menores).] Maus cavalos não impossibilitam o sucesso da viagem (zero cavalos sim); uma mente em frangalhos, um corpo lasso e a estupidez (tudo junto conotando uma carroça em pedaços), sim.

“When a man lacks understanding,

is unmindful and always impure;

He does not reach that final step,

but gets on the round of rebirth.”

Renascer tem quase sempre conotações positivas. Não aqui, seja para o hinduísmo conforme os exegetas hindus seja para mim, que me arrisco a uma interpretação ainda alhures, conectada a um outro mundo no aqui e agora. Nada pode ser pior do que o renascimento contínuo neste contexto. É o mesmo que ensinar a doutrina do eterno retorno para os fracos em Assim Falou Zaratustra. A bênção de uma “vida” eterna não é nada no colo de mortos-vivos. A sua odisséia não é completada, é só uma grande tortura sem-sentido. OM omento presente não tem um último degrau, mas o último degrau é necessário para os sentidos do homem (sua parte menos importante).

RESUMO DO CREDO HINDU SEGUNDO RAFAEL DE ARAÚJO AGUIAR (LEMBRANDO QUE UM LIMITE MÁXIMO – QUE CHAMAMOS DE DEUS – QUE NÃO SAIBA RIR DE SI É INÚTIL, TANTO EXISTINDO COMO APENAS ALMEJANDO EXISTIR, DÁ NO MESMO):

No que os intérpretes (todos os já consultados por mim, pelo menos) do hinduísmo e eu discrepamos é: para eles, sair da roda da existência é a libertação. Eu acredito que os Vedas genuinamente pregam, no lugar, o seguinte:

Om. Quando se diz que sair da roda da existência é a libertação, está-se dizendo isso para os tolos; pois são os tolos que lêem ensinamentos nos livros e sempre os absorvem da pior forma. Desta feita, não proibiremos a leitura aos tolos, mas nos certificaremos que eles sempre retirarão deste manancial de sabedoria a interpretação mais literal e espúria possível: para eles, escapar da roda da existência via santidade é a libertação suprema. Isto não é Brahman, mas seria pecaminoso contra a própria vida ensinar a verdadeira religião para aqueles que não a merecem. O texto está redigido de forma que os merecedores de absorvê-la saberão interpretar nosso único credo a contento. A libertação é oni-presente e inevitável, sempre esteve aqui e agora e sempre estará para o leitor puro e consciente (aquele que aspira à sabedoria na vida). Isto é Brahma. Não há reencarnações, esse é apenas um dogma regulador para os hOMens mais vis. O dOM da vida é único e especial, pois a morte não é o que se entende vulgarmente pela morte: ela não encerra nada. O presente é eterno. A realidade é una. Não há progressos, regressos, ciclos ou aléns. O fato de indivíduos nascerem e morrerem confunde as massas, porque quem se crê indivíduo tenta se colocar no lugar de outro indivíduo, no que sempre falhará até os mínimos detalhes. É preciso entender que a existência não é algo linear sobre o qual o tempo – condição de possibilidade da própria existência, mas apenas uma de suas engrenagens – tenha qualquer poder. O tempo só funciona de acordo cOM o próprio desígnio inerente do que se chama realidade ou existência. Ele, o tempo, serve a e é inseparável da vida mesma. E a individualidade, o nascer e perecer são elementos, fundamentos da existência. Não significa que os indivíduos crus sejam Brahman (a existência mesma). Mas estão equipados para entender Brahman e se tornar Brahman. Pois Brahman pensou em tudo desde o sempre, já que o tempo é apenas uma engrenagem sua e ‘sempre’ é apenas uma palavra vazia fora da percepção dos hOMens, ligada às grandes limitações dos sentidos. Início e fim só existem para os indivíduos que são tolos. Brahman só pode ser usufruído pelo que chamam de presente. A vida dos tolos é um eterno sofrer, e o que é mais irônico: um sofrer baseado em algo que não existe – sua dilaceração, sua aniquilação, sua morte. O pavor do fim. Pois eles não sabem que são eternos, e isso gera a contradição muito lógica de que eles sofrem eternamente devido mesmo a esta ignorância, que em certa medida é obra deles próprios, pois eles também são Brahman, em crisálida. A forma de reestabelecer a harmonia e a ressonância cOM Brahman, o real, é, cOMpreendendo o real, efetivá-lo (sendo real, vivendo o presente, isto é, a eternidade). Esta condição carece de sofrimento penoso; o que (os tolos) chamam de sofrimento, na vida de quem entendeu Brahman é apenas atividade e saúde, a plena realização do Brahman, separado em indivíduos apenas formalmente, para apreciação dos eternamente tolos, tolo Brahman brincalhão (a verdade é que cada um que cOMpreende Brahman é Brahman, e Brahman é indivisível)! Por que nós, Brahman, dar-nos-íamos ao trabalho de escrever de forma tão límpida para nós mesmos, Brahman, o que é Brahman, se Brahman (os tolos, agora, os Brahman não-despertos e necessários ao Brahman) ainda assim não irá entender, da mesma forma que lendo poesia e enigmas? Pois este ensinamento carece da possibilidade de ser entendido pela mera literalidade e baixeza vital. É preciso ler mais do que palavras, porque Brahman é mais do que palavras. O “inferno” de Brahman é que Brahman é tudo, e a tolice é parte indissociável deste único e melhor dos mundos, o sempre-existente. O inferno de Brahman é Brahman, mas Brahman não se importa, o que é, aliás, muito natural e desejável. Brahman é o mais vil e o mais alto, e nunca se pára de cair e nunca se pára de subir segundo o axiOMa inquebrantável de Brahman, o Um ou Ser ou Ente. Brahman é perfeito e não quer se liberar de Brahman. E nem poderia se assim desejasse. Om.

Digo que Brahman em algum momento através de mim achou de bom tom ser mais literal, para satisfazer Sua vontade (e a minha), quebrando as regras num sentido e duma forma infinitesimal que não descaracteriza Brahman, num limiar bastante desprezível do que os tolos chamam de tempo-espaço que eu traduziria em palavras como sendo minha vida, os anos que eu vivo (da perspectiva de uma terceira pessoa)¹ nos lugares que eu vivo em torno de quem eu vivo (meus amigos, coetâneos e leitores).

¹ O que é a terceira pessoa (tanto do ponto de vista metafísico quanto do ponto de vista gramatical de todas as línguas)? É a junção fictícia das duas primeiras pessoas. Eu sou a terceira pessoa de vocês; vocês são a terceira pessoa para mim. E no entanto a primeira pessoa sou eu (vocês, isoladamente) e a segunda pessoa são vocês em conjunto (eu e os outros, para vocês, individualmente).

“When a man’s mind is his reins,

intellect, his charioteer;

He reaches the end of the road,

That highest step of Vishnu.”

Com esse trecho não vou gastar saliva. Irei apenas traduzi-lo para o formato da prosa familiar a nossa cultura, omitindo as palavras desnecessárias para a compreensão total (não faz sentido, na tríade homem-mente-intelecto, pelo menos nessa tradução em inglês, conservar mind e intellect; só man já é mais do que o bastante):

“When a man (…) is (…) his charioteer, he reaches the end of the road, that highest step of Vishnu.”

“Higher than the senses are their objects;

Higher than sense[d?] objects is the mind;

Higher than the mind is the intellect;

Higher than the intellect is the immense self;”

“Mais elevados que os sentidos são as coisas que percebemos por via dos sentidos, o mundo visível; [Que eu citei acima, na hierarquização simplificada, como intelecção – esta parte do mundo visível não fazendo referência ao próprio sujeito, e para sermos sujeitos está implicado que tem de haver o binômio sujeito-objeto, pode ser omitida, inclusive porque a mente, como veremos abaixo, interpreta automatica-mente todas as percepções dos 5 sentidos, integrando-as, e não se pode falar de mundo visível (veja como nos expressamos sempre hiper-valorizando os olhos!)/sentido sem que haja a mente do ator dotando este mundo de sentido (bússola das sensações).]

Mais elevada que o mundo visível é a mente;

Mais elevado que a mente é o intelecto; [Aqui sinto que nosso pensar ocidental entra em colisão com o vocabulário hindu – ou será problema da tradução para o inglês? –, pois mente e intelecto estão indissociados de acordo com nossa maneira de representar a ambos. A terceira linha, como a segunda linha, devem ser omitidas numa tradução explicativa superior.]

Mais elevado que o intelecto é o imenso self.”

Para melhorar, destarte:

“Mais elevada que os sentidos é a consciência;

Mais elevado que a consciência é o inconsciente.”

(mundo animal < mundo humano < mundo divino [somos divinos!]) (*) O mais irônico, se seguíssemos o ‘roteiro’ do Veda seria que posicionaríamos o mundo mineral acima do animal, i.e., o mundo visível, os objetos, as coisas, a estrada que os cavalos percorrem como sendo mais importantes até que nosso tato, audição, visão, olfato e paladar, o que é absurdo, pois não vivemos em subserviência aos objetos, e sim o contrário: somos nós que os criamos graças a nossa condição de seres vivos, por assim dizer.

A palavra que mais pode gerar confusão na tradução aperfeiçoada acima é a última. O inconsciente é o sábio que mora em nós sem que possamos ou devamos cobrar aluguel. Na verdade é ele que nos sustenta, em grau ainda mais surpreendente que a consciência sustenta os meros instintos. Porém, o INCONSCIENTE sofreu muitas malversações nos últimos tempos. Não temos palavra melhor para caracterizar “o verdadeiro senhor da consciência”, mas infelizmente a psicanálise poluiu imensamente essa palavra, para não falar das (más) psiquiatrias, psicologias e filosofias (jamais leiam Von Hartmann, um homem que interpretou Schopenhauer da pior maneira possível e teve grande influência sobre os ‘apreciadores da filosofia’). É preciso decantar e esterilizar a palavra para reutilizá-la, não temos escolha, e na verdade não devíamos nos subjugar a algumas poucas gerações de tolos, ou teríamos de reinventar nomes para quase todas as coisas. Mesmo assim, para iniciar esse processo e a revalorização do termo inconsciente, bem-descrito no Veda como imenso, muito mais abrangente que a consciência (como o oceano perante uma piscina), vindo a ser em última instância tão importante que pode ser igualado a Brahman, já que qualquer entidade separada de nós e portanto de nossa instância mais elevada seria apenas criar quimeras e fábulas que só multiplicariam as complicações, quando sabemos que o que o hinduísmo diz é que somos Brahman, ao contrário do cristianismo, que estabelece um Deus infinitamente inacessível ao homem, tão inacessível que se tornou a religião favorita do niilista ocidental,¹ quer dizer, maioria da população, que é niilista sem o saber… Em suma, quero dizer que de uma forma ou de outra, se quisermos respeitar o credo hindu, devemos equiparar a noção “despoluída” de inconsciente ao Todo desta querida religião. Seja falando simplesmente inconsciente, seja empregando, se se quiser, o termo inconsciente coletivo de Jung.

¹ Podemos até dizer que quanto mais crente se é, mais ateu! Só uma religião tão mesquinha seria capaz de provocar a morte teórica de deus, gerando tamanho estrago civilizacional que os filósofos tiveram de interferir nos negócios dos padrecos!

Por outro lado, se ainda assim o leitor fizer questões de sinônimos, como mais acima, para me referir a ‘inconsciente’, recorreria a:

BRAHMAN = OM = INCONSCIENTE (COLETIVO) (Filosofia, Psicologia, Jung) = UM (Parmênides) = DAIMON (Sócrates) = Idéia (Platão)¹ = MUNDO (vulgar) = OUTRO MUNDO (Filosofia Ocidental)² = VONTADE DE POTÊNCIA ou VONTADE NÃO-UNA ou VONTADE NÃO-LIVRE (Nietzsche)³ = VIDA DO SÁBIO (hinduísmo e outros sistemas) = ETERNIDADE ou PRESENTE ETERNO4

¹ Como Sócrates não escreveu, estamos autorizados a referir o daimon socrático ao próprio gênio de Platão: tão “egoísta” que criou dois nomes para Brahman ou aquilo que há de mais sagrado!

² Emprego aqui o Outro Mundo no sentido “recuperado” que já demonstrei, em relação ao Além da maioria das religiões: o Outro Mundo é o mundo das Idéias de Platão, localizado na alma do sábio, e portanto neste mundo mesmo, no presente, aqui e agora. Esse é o tesouro máximo do hinduísmo: uma religião de massa que não nega o amor à vida e não incita à hipocrisia e à mentira, prometendo recompensas num futuro indefinido. O que é do sábio sempre foi, é e será do sábio. A eternidade já foi alcançada. Desde pelo menos Schopenhauer ou Kierkegaard (admito que Kant é um caso talvez especial; já Hegel acreditava apenas num canhestro progresso da História, sem entender que o presente já havia trazido todas as evoluções que ele só podia atribuir ao futuro da Europa), após o longo e sombrio hiato entre Platão e o mundo moderno (quase ainda ontem!), chegando ao trabalho de autores definitivamente afirmadores de um e somente um mundo, este aqui, como Husserl, Heidegger, os existencialistas, praticamente todos os filósofos dignos do século passado e deste, o Outro Mundo dos fanáticos religiosos e dos Escolásticos – considerados filósofos apenas nominalmente, meros escribas de patrões temporais (a Igreja) – foi abandonado em prol de uma nomenclatura despida de conotações deletérias, fraudulentas e niilistas: o Outro Mundo de que falo, sinônimo da nova Zeitgeist de retorno ao Oriente, é o Outro Mundo que eu interpreto estar exposto nos Vedas: o mundo do sábio que chegou à realização de que a eternidade é o presente. O reencantamento do mundo; por isso também incluo a palavra mundo, porque é no mundo que vivemos, e em nenhum outro, em que tudo é possível. Este mundo é o Um.