O Capítulo 7 já foi contemplado em

https://seclusao.art.blog/2019/12/26/historia-da-matematica-uma-visao-critica-desfazendo-mitos-e-lendas-tatiana-roque-2012-capitulo-7-o-seculo-xix-inventa-a-matematica-pura-ou-a-era-do/. A seguir, citações dos demais.

Anexo: A história da matemática e sua própria história

“Quase todos esses autores escreveram seus textos mais importantes antes dos anos 1970, logo, sua visão sobre a história da matemática já pode ser considerada ultrapassada. Não queremos desmerecer o trabalho desses pioneiros, que ajudaram a fundar a história da matemática como campo de pesquisa e motivaram o interesse de inúmeros jovens por essa área. A intenção aqui é ressaltar que suas obras continuam a ser citadas sem uma visão crítica, ainda que inúmeros trabalhos históricos, nas últimas décadas, tenham desmentido e questionado grande parte das afirmações nelas reproduzidas. Até esse momento, os livros de história da matemática eram escritos, principalmente, por matemáticos e professores. A década de 1970 marcou uma virada na historiografia, pois a profissão de <historiador da matemática> começou a existir. Tal mudança se deu primeiramente nos Estados Unidos, mas também em outros países, cuja produção histórica anterior também era intensa, apesar de menos conhecida no Brasil.

A história da matemática teve um período de grande atividade na Europa entre as últimas décadas do século XIX e a Primeira Guerra Mundial. Um exemplo é a obra monumental do matemático alemão Moritz Cantor, Vorlesungen über Geschichte der Mathematik (Preleções sobre a história da matemática), publicada em 4 volumes entre 1880 e 1908 (este último volume com colaboradores), cobrindo um longo período: dos tempos antigos até 1200; de 1200 a 1668; de 1668 a 1758; e de 1759 a 1799. Outra iniciativa colossal foi a organização da Encyklopädie der mathematischen Wissenschaften (Enciclopédia das ciências matemáticas), coordenada por Felix Klein, que pretendia servir de fonte para uma visão geral sobre a área naquele momento, mas também sobre sua pré-história. O período foi marcado ainda por inúmeras edições de trabalhos originais de matemáticos renomados do passado, como as traduções dos textos gregos feitas por J.L. Heiberg (para o alemão), T.L. Heath (para o inglês) e P. Tannery (para o francês). Não é difícil imaginar que o período entre-guerras tenha interrompido essa intensa produção européia relacionada à história da matemática, um campo de pesquisas então incipiente. Depois da Segunda Guerra, houve trabalhos pontuais, como os de Otto Neugebauer, que, a partir de 1929, passou a liderar um grupo de historiadores sobre as matemáticas antiga e árabe. Estudos sobre outros períodos da história eram escassos, em parte devido ao predomínio da visão positivista em filosofia, mas também em outras áreas, o que pode ter influenciado os matemáticos e outros pesquisadores a pensarem que a <história era bobagem>.”

“1960 (…) Esse é um ano importante, pois marca a fundação de uma das revistas mais conhecidas até hoje dedicada especificamente ao tema: Archive for History of Exact Sciences. Apesar de esse periódico também ter divulgado, desde seus primeiros números, artigos de história da matemática, o movimento para reconhecer a história da ciência como área de pesquisa não foi acompanhado, de imediato, por um esforço similar para institucionalizar a história da matemática.”

“É curioso constatar que Uma história da matemática, livro escrito por Florian Cajori nas primeiras décadas do século XX, tenha sido traduzido para o português em 2007. Apesar de poder interessar à história da história da matemática, essa obra é bastante desatualizada.”

“Para combater o eurocentrismo, não nos parece profícuo tentar mostrar que o que os europeus descobriram já estava presente em outras culturas. Lançar-se em uma busca desenfreada pelas raízes não-européias da matemática pode levar alguns autores a exagerar para o outro lado, caso do best-seller de G.G. Joseph, Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics, publicado em 1991, em Londres, pela I.B. Taurus.”

“Sabetai Unguru, romeno que estudou filosofia e história da matemática em Israel e nos EUA, publicou em 1975 o polêmico artigo On the need to rewrite the history of mathematics, dirigindo forte crítica às histórias da matemática grega mais reconhecidas naquele momento, entre as quais se incluíam as de Neugebauer e de B.L. van der Waerden. Nesse artigo, os antigos historiadores da matemática grega são desqualificados como <matemáticos> e suas teses são apontadas como anacrônicas, marcadas por reconstruções racionais dos conteúdos com base na diferença entre necessidade lógica e necessidade histórica. Tal polêmica foi crucial para a definição da personalidade da história da matemática, contrastando interpretações conceituais, baseadas em uma imagem moderna da matemática, com estudos históricos que levavam em conta o contexto cultural.”

“Os trabalhos inovadores de Jöran Friberg, Jens Høyrup e Eleanor Robson, nos anos 80 e 90, transformaram de modo irreversível a imagem da matemática mesopotâmica, antes estudada por meio de reconstruções anacrônicas. A mesma revolução não aconteceu na história que aborda períodos mais recentes. O estudo da matemática na Idade Média e no Renascimento recebeu a influência dessas transformações no modo de fazer história, incluindo análises mais contextualizadas sobre o desenvolvimento geral da ciência, bem como da visão sobre a ciência na época. Mas a história da matemática moderna, que reconhecemos como mais próxima da nossa, está apenas começando a ser reescrita.”

“Um livro geral de história da matemática que pretende levar em conta essas novas pesquisas, cobrindo inclusive épocas mais recentes, é A History of Mathematics: an Introduction, publicado por V. Katz em 1993 e traduzido para o português como História da matemática. Trata-se de uma fonte confiável que, no entanto, devido à sua extensão, apresenta alguns temas de forma bastante resumida.”

“Ainda que o significado de noções como generalidade, universalidade e demonstração tenha mudado ao longo da história, o trabalho matemático foi executado, em diferentes momentos, como uma atividade demonstrativa, almejando produzir resultados segundo regras próprias a uma época dada. Os processos de abstração, bem como as manipulações simbólicas por meio das quais eles se manifestam, possuem uma história e foram traços característicos da prática matemática – sobretudo em épocas mais recentes – e, como tais, precisam ser analisados de perto.”

CAPÍTULO 1. Matemáticas na Mesopotâmia e no antigo Egito

“Como nosso objetivo é relacionar a história dos números com a história de seus registros, é preciso abordar o nascimento da escrita, que data aproximadamente do quarto milênio antes da Era Comum. Os primeiros registros que podem ser concebidos como um tipo de escrita são provenientes da Baixa Mesopotâmia, onde atualmente se situa o Iraque. O surgimento da escrita e o da matemática nessa região estão intimamente relacionados.”

“Em seguida, a região foi dominada por um império cujo centro administrativo era a cidade da Babilônia, habitada pelos semitas, que criaram o Primeiro Império Babilônico. Os semitas são conhecidos como <antigos babilônios>, e não se confundem com os fundadores do Segundo Império Babilônico, denominados <neobabilônios>. Data do período babilônico antigo (2000-1600 a.E.C.) a maioria dos tabletes de argila mencionados na história da matemática.

babilônicos (judeus) x mesopotâmicos (babilônios!)

“Por exemplo, o tablete YBC 7289 diz respeito ao tablete catalogado sob o número 7289 da coleção da Universidade Yale (Yale Babilonian Collection). Outras coleções são: AO (Antiquités Orientales, do Museu do Louvre); BM (British Museum); NBC (Nies Babylonian Collection); Plimpton (George A. Plimpton Collection, Universidade Columbia); VAT (Vorderasiatische Abteilung, Tontafeln, Staatliche Museen, Berlim).”

“Os registros disponíveis são mais numerosos para a matemática mesopotâmica do que para a egípcia, provavelmente devido à maior facilidade na preservação da argila usada pelos mesopotâmicos do que do papiro, usado pelos egípcios.”

“A escrita, no período faraônico, tinha dois formatos: hieroglífico e hierático. O primeiro era mais utilizado nas inscrições monumentais em pedra; o segundo era uma forma cursiva de escrita, empregada nos papiros e vasos relacionados a funções do dia a dia, como documentos administrativos, cartas e literatura. Os textos matemáticos eram escritos em hierático e datam da primeira metade do segundo milênio [antes de Cristo], apesar de haver registros numéricos anteriores.”

“Høyrup (…) mostrou que a <álgebra> dos babilônicos estava intimamente relacionada a um procedimento geométrico de <cortar e colar>. Logo, tal prática não poderia ser descrita como álgebra, sendo mais adequado falar de <cálculos com grandezas>.”

“Centenas de tabletes arcaicos indicavam que a escrita já existia no quarto milênio, pois continham sinais traçados ou impressos com um determinado tipo de estilete. O material contradizia a tese pictográfica, pois nessa fase inicial da escrita as figuras que representavam algum objeto concreto eram exceção. Diversos tabletes traziam sinais comuns que eram abstratos, isto é, não procuravam representar um objeto. Assim, o sinal para designar uma ovelha não era o desenho de uma ovelha, mas um círculo com uma cruz.”

“Eles não representavam números, como 1 ou 10, mas eram instrumentos particulares que serviam para contar cada tipo de insumo: jarras de óleo eram contadas com ovóides; pequenas quantidades de grãos, com esferas. Os tokens eram usados em correspondência um a um com o que contavam: uma jarra de óleo era representada por um ovóide; duas jarras, por dois ovóides; e assim por diante.” “Isso quer dizer que o fato de associarmos um mesmo símbolo, no caso 1, ou um cone, a objetos de tipos distintos, como ovelhas e jarras de óleo, consiste em uma abstração que não estava presente no processo de contagem descrito anteriormente.”

“A descoberta dos tabletes de Uruk levou ao desenvolvimento de um projeto dedicado à sua interpretação, que começou por volta dos anos 1960, em Berlim. A iniciativa foi fundamental para a compreensão dos símbolos encontrados e deu origem à obra que esclareceu o contexto desses registros: Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East (Contabilidade arcaica: escrita antiga e técnicas de administração econômica no antigo Oriente Próximo), de H.J. Nissen, P. Damerow e R.K. Englund. Ficou claro, a partir daí, que os registros serviam para documentar atividades administrativas e exibiam um sistema complexo para controlar as riquezas, apresentando balanços de produtos e contas.”

“Havia mais de 6 sistemas de capacidade usados para diferentes tipos de grãos e de líquidos. Ao passo que os objetos discretos eram contados em base 60, a contagem de outros produtos empregava a base 120. Além disso, havia métodos distintos para contar tempo e áreas.”

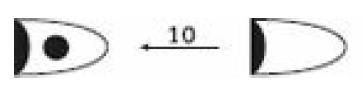

“Uma cunha pequena representava uma unidade de grãos, a unidade básica do sistema de medidas dos sumérios. Uma quantidade 6x maior era representada pela marca circular, e outra 10x maior que esta última, por um círculo maior”

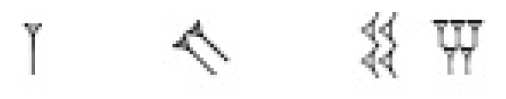

ESTILO PROTOCUNEIFORME

(Ler da direita para a esquerda. – As imagens não são ‘números’ como no Ocidente, apenas de forma algo relativa. – Na 1ª imagem-seqüência [figura], demonstra-se uma figura que é um dez avos de outra e portanto outra que é 10x a primeira; na segunda figura assume-se a representação numérica abstrata ocidental para facilitar o raciocínio, entre aspas – a unidade “10”, que podia ser qualquer outro número inteiro ou fração, seis vezes menor que a unidade “60”, esta 10x menor que a unidade “600”, e assim por diante. Como a primeira imagem da 2ª figura difere da primeira imagem da 1ª figura, bem como da 2ª imagem da 1ª figura – mas note-se a semelhança da bola preta que na figura mais acima é apenas uma parte de um todo maior, indicando uma lógica interna –, vê-se que a representação numérica ou contagem pode iniciar de qualquer representação simbólica.)

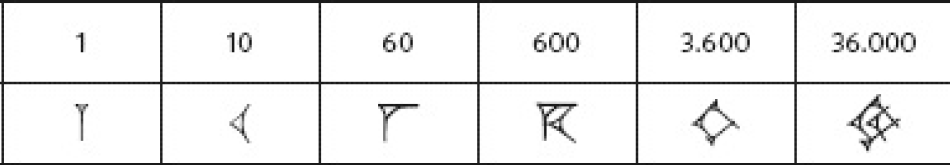

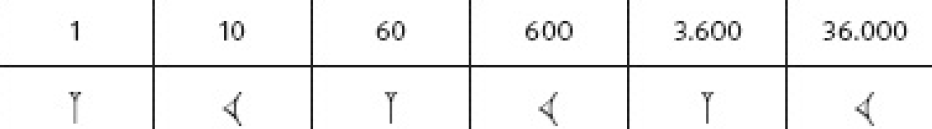

TRANSIÇÃO AO ESTILO CUNEIFORME “MADURO”

Aparição das primeiras notações fixas

= 1

(cunha simples)

= 10

(ponto ou esfera)

= 60

(cunha aumentada)

= 600

(cunha com ponto ou esfera)

= 3600

(ponto aumentado ou esfera aumentada)

= 36000

(ponto dentro de outro ponto / esfera dentro de outra esfera / notação dos 3 círculos preto e branco contrastados em relação de contido e contém / ou ainda “esfera com raias”)

Outras notações foram aparecendo:

Fase tardia da evolução (reprise intercalada dos sinais, a cada multiplicação por 60):

Toda simplificação é uma complexificação!

“O sistema sexagesimal posicional usado no período babilônico deve ter surgido da padronização desse sistema numérico, antes do final do terceiro milênio [a.C.]. Ainda que a representação numérica continuasse a ser dependente do contexto e a usar diferentes bases ao mesmo tempo, aos poucos começaram a ser registradas listas que resumiam as relações entre diferentes sistemas de medida.”

“Na verdade, presume-se que muitos dos tabletes que nos fornecem um conhecimento sobre a matemática babilônica tinham funções pedagógicas.”

“Sobre a tradução dos textos cuneiformes, ver Gonçalves, Observações sobre a tradução de textos matemáticos cuneiformes.”

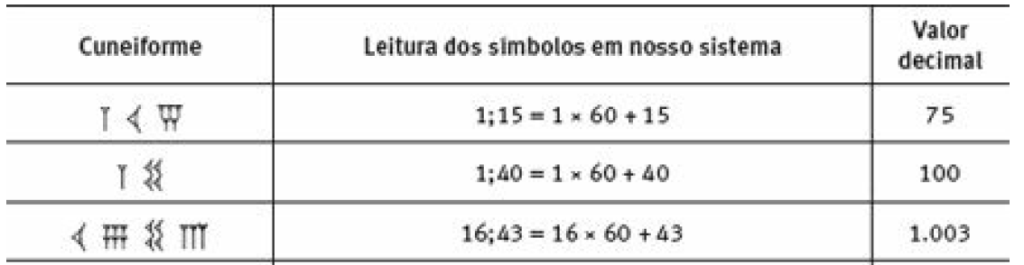

“O sistema que usamos para representar as horas, os minutos e os segundos é um sistema sexagesimal [o nosso possui literalmente 60 valores, já que 0 = 60; o cuneiforme, 59, já que não há o zero e 1 = 60.].”

“Nosso sistema de numeração de base 10 também é posicional. Há símbolos diferentes para os números de 1 a 9, e o 10 é representado pelo próprio 1, mas em uma posição diferente. Por isso se diz que nosso sistema é um sistema posicional de numeração de base 10, o que significa que a posição ocupada por cada algarismo em um número altera seu valor de uma potência de 10 para cada casa à esquerda.”

“Se considerarmos 125 escrito na base 60, estaremos representando 1 × 60² + 2 × 60¹ + 5 × 600, que é igual a 3725 na base 10.”

“Suponhamos agora que, em vez de usar a base 10, queiramos escrever um número em um sistema de numeração posicional cuja base genérica é b. Para representar um número N qualquer nessa base b, escrevemos:

N = anbn + an−1bn−1 + … + a0b0 + a−1b−1 + … + a−mb−m + ….

Isso significa que anbn + an−1bn−1 + … + a0b0 é a parte inteira e temos que a−1b−1 + … + a−mb−m + … é a parte fracionária desse número.”

“Como na base 60 podemos ter, em cada casa, algarismos de 1 a 59, empregaremos o símbolo ; como separador de algarismos dentro da parte inteira ou dentro da parte fracionária de um número.” “Por exemplo, no número 12;11,6;31 a parte inteira é constituída por dois algarismos (12 e 11); e a parte fracionária por outros dois (6 e 31).”

12;11 neste caso = no nosso sistema a:

12 x 60¹ + 11 x 600 =

12 x 60 + 11 =

720 + 11 =

731

O número após a vírgula 6;31 assim se resolve:

6 x 60-1 + 31 x 60-2 =

6 x 1/60 + 31 x 1/3600 =

6/60 + 31/3600 =

1/10 + 0,00861… =

0,10861…

Logo, 12;11,6;31 =

731 + ~0,10861 =

~731,1086 =

~731,11

“Que mecanismo utilizamos em nosso sistema de numeração para indicar a posição de um símbolo? Por exemplo, como fazemos para que o 1 do número 1 tenha um valor distinto do 1 do número 10?”

“Observe-se que esse sistema dá margem a algumas ambigüidades. Por exemplo, o mesmo símbolo podendo ser lido como (1 + 1) ou (1;1) [ou seja, como 2 ou 61 da notação decimal]. (…) Nesse caso, houve uma época em que se usava o símbolo com tamanhos diferentes para representar o 60 e o 1, hábito que talvez esteja na origem do sistema posicional.” Quer seja: sem escala ou casas decimais, ficamos incapacitados de resolver informações polissêmicas, a não ser que, por exemplo, fosse evidente, digamos, pelo número de cabeças visíveis num rebanho, a qual grandeza o símbolo faria referência.

“Algumas vezes era deixado um espaço entre os dois símbolos para marcar uma coluna vazia. Mas essa solução não resolve o problema de expressar uma coluna vazia no fim do número, logo, permite diferenciar 7200 de 3601, p.ex., mas não 7200 de 2 e de 120.”

ADIÇÃO EM BASE 60

1;30,27;40 + 29,15;13 = 1;59,42;53

1;59 + 1 = 2

MULTIPLICAÇÃO EM BASE 60

4 x 20 = 1;20

DIVISÃO EM BASE 60

1,30 ÷ 3 =0,30

(raciocínio análogo a: 1h30 dividido por 3 é igual a meia-hora. A coisa se complicaria muito se o segundo número possuísse casa fracionária [sessentesimal e não decimal].)

Por óbvio, multiplicações, divisões, somas e subtrações por 60 são as operações mais simples.

“Uma das vantagens do sistema sexagesimal é o fato de que o número 60 é divisível por todos os inteiros entre 1 e 6, o que facilita a inversão dos números expressos nessa base. A divisibilidade por inteiros pequenos é uma importante característica a ser levada em conta no momento da escolha de uma base para representar os números. A base 12 está presente até hoje no comércio, onde usamos a dúzia justamente pelo fato de o número 12 ser divisível por 2, 3 e 4 ao mesmo tempo. Não podemos dizer, no entanto, que esse tenha sido o motivo do emprego dessa base pelos mesopotâmicos.”

“No sistema posicional, podem-se usar os mesmos símbolos para escrever números inteiros e números fracionários, o que não acontece no sistema egípcio, como veremos adiante.”

“Uma grande vantagem do sistema posicional é permitir a escrita de números muito grandes com poucos símbolos. Efetivamente, mais tarde, quando os babilônios iniciaram seus estudos astronômicos, tornou-se necessário escrever números maiores, fazendo com que as características posicionais se tornassem mais evidentes.”

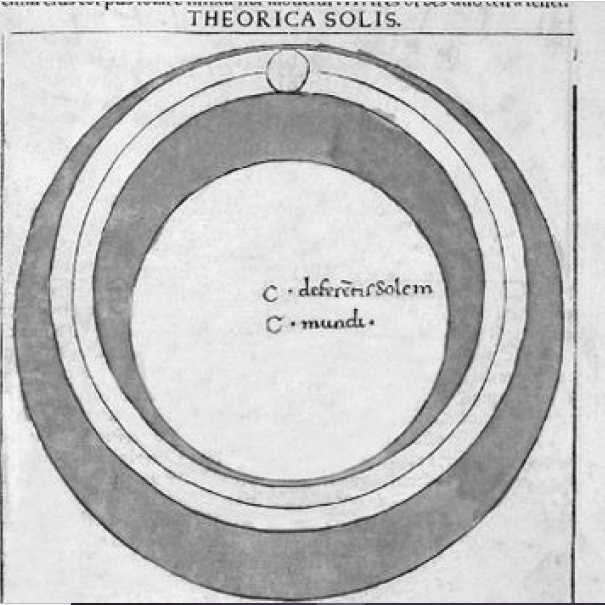

“A observação dos corpos celestes, presente nos registros da matemática babilônica do primeiro milênio a.C., bem como a aritmética e o sistema posicional sexagesimal usados nesse contexto, pode ter tido influência sobre a tradição grega de Hiparco e Ptolomeu. A astronomia desenvolvida por eles no Egito, na virada do milênio, indica que os cálculos astronômicos e trigonométricos de então eram feitos por meio do sistema sexagesimal posicional, ainda que com uma simbologia distinta, e que este permaneceu sendo o principal sistema até a introdução do sistema decimal indo-arábico, muitos séculos depois. Apesar disso, a idéia de que teria havido uma continuidade entre as matemáticas mesopotâmica e grega foi construída com base em interpretações equivocadas e não há evidências nítidas da influência dos mesopotâmicos sobre a tradição grega.”

“Os astrônomos selêucidas, talvez pela necessidade de lidar com números grandes, chegaram a introduzir um símbolo para designar o zero, ou melhor, uma coluna vazia. No caso de 3601, escrevia-se 1; separador; 1. O separador era simbolizado por dois traços inclinados:

1 ; // ; 1 =

3601

“A noção de zero como número só surgirá quando ele começar a ser associado a operações, em particular, ao resultado de uma operação, como 1 – 1 = 0. Escrever uma história do zero é tarefa bastante complexa, pois devem ser levados em conta, antes de tudo, os diversos contextos em que ele aparece e o que essa noção pode significar em cada contexto.”

“No caso da multiplicação, o uso de tabuadas em tabletes era fundamental. Basta observar que os cálculos elementares, ou seja, aqueles que correspondem à nossa tabuada, incluem multiplicações até 59 × 59! Isso pode indicar a necessidade de tabletes mesmo para os cálculos mais elementares.

Um exemplo de tablete de multiplicação por 25:

1 (vezes 25 é igual a) 25

2 (vezes 25 é igual a) 50

3 (vezes 25 é igual a) 1;15

4 (vezes 25 é igual a) 1;40

5 (vezes 25 é igual a) 2;05

6 (vezes 25 é igual a) 2;30

7 (vezes 25 é igual a) 2;55 etc.”

“O procedimento de divisão empregado pelos babilônios nos leva a concluir que a utilização dos tabletes, nesse caso, não servia apenas à memorização de tabuadas, o que seria um papel acessório. Para que a técnica adotada na divisão fosse rigorosa, devia haver uma necessidade intrínseca de se representar em tabletes as divisões por números cujos inversos não possuem representação finita em base 60. Isso porque, no caso de 1/N não possuir representação finita, o resultado da divisão de M por N teria de estar registrado em um tablete. Se essa operação fosse realizada pelo procedimento usual, ou seja, multiplicando-se M por 1/N, o resultado obtido não seria correto, da mesma forma que não seria correto fazer 6 × 0,3333…(=1/3) para dividir 6 por 3.”

“Além das operações de soma, subtração, multiplicação e divisão, os babilônios também resolviam potências e raízes quadradas e registravam os resultados em tabletes. O método usado nesse último caso era bastante interessante, uma vez que permitia obter valores aproximados para raízes que hoje sabemos serem irracionais.”

“Além dos tabletes contendo o resultado de operações, os babilônios tinham um certo número de tabletes de procedimentos, como se fossem exercícios resolvidos. Correspondiam a problemas que trataríamos hoje por meio de equações. Analisaremos alguns deles em detalhes, com a finalidade de mostrar como seria anacrônico considerar que os babilônios soubessem resolver equações.”

“A generalidade dos algoritmos babilônicos é distinta, pois eles constroem uma lista de exemplos típicos, interpolando-os, em seguida, para resolver novos problemas.”

“Desde a época grega, e pelo menos até o século XVII, a geometria teve de respeitar a homogeneidade das grandezas. Isso quer dizer que não era permitido somar uma área com um segmento de reta. A operação utilizada pelos babilônios revela que eles não experimentavam nenhuma dificuldade nesse sentido, uma vez que possuíam um modo concreto de transformar um segmento de reta em um retângulo, operação traduzida aqui como <projeção>.”

“Exemplos como esse, envolvendo operações de <cortar e colar> figuras geométricas parecem ter sido comuns na época. Høyrup caracteriza essas práticas como uma <geometria ingênua>.”

“Se definíssemos álgebra como um conjunto de procedimentos que devem ser aplicados a entidades matemáticas abstratas, poderíamos até concluir que os babilônios realizavam uma álgebra de comprimentos, larguras e áreas. Mas, nesse caso, deveríamos ter o cuidado de definir a álgebra dos babilônios de um modo particular, e não por extensão do nosso conceito moderno de álgebra.”

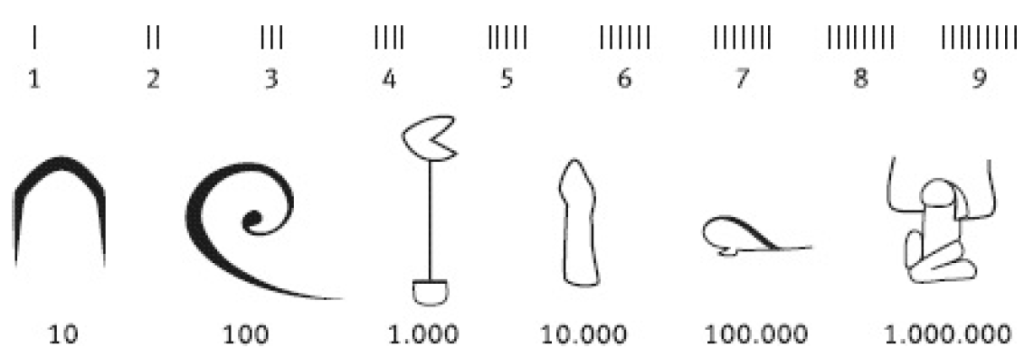

“O sistema decimal egípcio já estava desenvolvido por volta do ano 3000 [a.C.], ou seja, antes da unificação do Egito sob o regime dos faraós. O número 1 era representado por uma barra vertical, e os números consecutivos de 2 a 9 eram obtidos pela soma de um número correspondente de barras. (…) O número 10 é uma alça [parece um pórtico ou uma ferradura apontando para o céu]; 100, uma espiral; mil, a flor de lótus; 10 mil, um dedo; 100 mil, um sapo; e 1 milhão, um deus com as mãos levantadas.” Quanta inocência! Ou serei eu muito malicioso? Veja abaixo…

Impossível não associar a notação egípcia a motivos religiosos ou sexuais – particularmente o 10 mil (caractere fálico) e o 1 milhão (duas interpretações instantâneas: 1- mão segura pênis e realiza-se, no topo, felação; 2- analogamente, pessoa ajoelhada em prece, com braços soerguidos), mas também o 100 mil, que remete a girino, embora não possamos dizer que se soubesse o formato de um espermatozóide (nem por isso deixava de haver uma noção, comprovada mitologicamente, de que ‘a vida veio da água’).

“os números são obtidos pela soma de todos os números representados pelos símbolos (sistema aditivo) (…) esse sistema não é adequado para representar números muito grandes (…) Cabe notar que os romanos lidavam com números grandes [mesmo] usando um sistema aditivo, o que relativiza esta afirmação.”

Somente as frações ½, 1/3, 2/3 e ¼ possuíam símbolos próprios (exclusivos).

“Nosso numerador indica quantas partes estamos tomando de uma subdivisão em um dado número de partes. Na designação egípcia, o símbolo oval [uma espécie de auréola sobre o símbolo usual do número] não possui um sentido cardinal, mas ordinal. Ou seja, indica que, em uma distribuição em n partes iguais, tomamos a n–ésima parte, aquela que conclui a subdivisão em n partes. É como se estivéssemos distribuindo algo por n pessoas e 1/n é quanto cada uma irá ganhar. Logo, configura-se um certo abuso de linguagem dizer que, na representação egípcia, as frações possuem ‘numerador 1’. Seria mais adequado dizer que essas frações egípcias representam os inversos dos números.”

Como eles representavam frações de numerador >1?

R: 5/8 seriam ½ + 1/8. (I)

Outros ex.:

(II) 58/87 = ½ + 1/6

(III) 3/7 = 1/3 + 1/11 + 1/231

“Se quisermos saber, em nossa representação, qual a maior de duas frações teremos de igualar os denominadores. Na representação egípcia, uma inspeção direta permite dizer qual a maior das duas frações”

“A palavra <aha> é traduzida por <número> ou <quantidade>, e esses problemas eram procedimentos para encontrar uma quantidade desconhecida quando é dada uma relação com um resultado conhecido.”

O INÍCIO DAS SUPERSTIÇÕES SOBRE “NÚMEROS RUINS”? “a duplicação de frações de denominador ímpar, um cálculo ‘difícil’, era realizada apenas uma vez, e sempre que se necessitasse do resultado recorria-se às tabelas. Pelo mesmo motivo, as somas de frações também traziam dificuldade e deviam ser representadas em tabelas.”

“Esses exemplos são citados em diversos livros, muitas vezes com o objetivo de indicar que os povos babilônicos e egípcios possuíam aproximações para o valor de π. Nosso objetivo é entender em que contexto tais problemas se inserem e em que medida podem ser ou não considerados instâncias primitivas da utilização de π. Para abreviar, evitamos entrar em detalhes sobre as unidades de medida utilizadas.”

“Exemplo egípcio (Problema 41 do papiro de Rhind): <Fazer um celeiro redondo de 9 por 10.> O celeiro tem o formato de um cilindro e a primeira parte do problema consiste em calcular a área da base, em forma de circunferência, cujo diâmetro é 9. A segunda parte consiste em calcular o volume em grãos se a altura é 10. O procedimento para resolver a primeira parte é o seguinte:

1) Subtraia 1/9 de 9. Resta: 8.

2) 8*8 = 64

A1 = 64

“O valor 1/9 é uma constante que devia ser aprendida e utilizada sempre que se quisesse calcular a área de uma circunferência (multiplicando essa constante pelo diâmetro). (….) O resultado deveria ser multiplicado por ele mesmo”

No ocidente:

A = π*R² = (8/9*d)² = (8/9*2)²*r²,

em que d é o diâmetro dado.

π = ~3,16,

“Daí a afirmação, apressada, contida em alguns livros de história, de que os egípcios já possuíam uma aproximação para π.”

“Exemplo babilônico (Haddad 104): <Procedimento para um tronco. Sua linha divisória é 0,05. Quanto ele pode armazenar?>”

“<Linha divisória> é o diâmetro da circunferência determinada por uma seção transversal. Em primeiro lugar, calculava-se a área de uma seção transversal, de forma circular:

1) Triplique a linha divisória:

3*0,05 = 0,15

2) Faça o quadrado de 0,15:

(0,15)² = 0,03;45

3) Multiplique 0,03;45 novamente pela linha divisória:

Abase = 0,03;45*0,05 = 0,00;18;45

4) Multiplicar a área da base pela altura:

Abase*Alt.

“A altura era considerada implicitamente como igual ao diâmetro.”

“Lembramos que a fórmula usada atualmente para o perímetro da circunferência é 2πr = πd (onde d é o diâmetro). Poderíamos dizer que o método dos babilônios não está muito longe do nosso, usando 3 como valor aproximado de π. Mas o objetivo não é calcular o perímetro e sim a área da circunferência, que, em seguida, deverá ser multiplicada pela altura. Para calcular a área a partir do perímetro, temos de elevar ao quadrado e depois dividir o resultado por 4π (basta verificar na nossa fórmula que a área πr² = (π²*d²)/4π). Mas, considerando que os babilônios usavam 3 como constante, em base 60, dividir por 4π é equivalente a multiplicar por 0,5 (pois 1/4π = 1/12 = 5/60 é o mesmo que 0,5 em base 60). Isso explica a multiplicação por essa constante”

“Seria um tremendo anacronismo dizer que os povos mesopotâmicos e egípcios já possuíam uma estimativa para π, pois esses valores estavam implícitos em operações que funcionavam, ao invés de serem expressos por números considerados constantes universais, como em nossa concepção atual sobre π.”

“Contar, e registrar quantidades, pode ser dita uma atividade concreta, pois implica um corpo a corpo com os objetos contados. Quando os tokens eram manipulados na contagem, e mesmo quando eram impressos na superfície dos invólucros, essa concretude estava em jogo. A abstração tem lugar a partir do momento em que o conteúdo dos invólucros podia ser esquecido, levando a um registro independente do que estava sendo contado, impresso em tabletes.”

“É MUITO COMUM LERMOS que a geometria surgiu às margens do Nilo, devido à necessidade de medir a área das terras a serem redistribuídas, após as enchentes, entre os que haviam sofrido prejuízos. Essa hipótese tem sua origem nos escritos de Heródoto, datados do século V a.C.: <Quando das inundações do Nilo, o rei Sesóstris enviava pessoas para inspecionar o terreno e medir a diminuição dos mesmos para atribuir ao homem uma redução proporcional de impostos. Aí está, creio eu, a origem da geometria, que migrou, mais tarde, para a Grécia>” “Além disso, quase todos os livros de história da matemática a que temos acesso em português reproduzem a lenda de que a descoberta dos irracionais provocou uma crise nos fundamentos da matemática grega. Alguns chegam a afirmar que tal crise só foi resolvida com a definição rigorosa dos números reais, proposta por Cantor e Dedekind no século XIX (ou seja, mais de vinte séculos depois).”

Matemáticos célebres da Grécia Antiga em ordem cronológica:

1. Tales

2. Pitágoras

3. Euclides

CAPÍTULO 2. Lendas sobre o início da matemática na Grécia

“O testemunho de Heródoto, apresentado no segundo dos nove livros de suas Histórias, se insere em uma descrição dos costumes e das instituições de povos diversos e é parte das investigações sobre as causas das guerras entre gregos e bárbaros (pertencentes ao império persa). Esse segundo livro é inteiramente consagrado ao Egito e nele se encontra a menção à palavra grega <geometria>. Os egípcios teriam revelado que seu rei partilhava a terra igualmente entre todos, contanto que lhe fosse atribuído um imposto na base dessa repartição. Como o Nilo, às vezes, cobria parte de um lote, era preciso medir que pedaço de terra o proprietário tinha perdido, com o fim de recalcular o pagamento devido.” “A palavra geometria pode ser traduzida, portanto, como <medida da terra>. Vem daí a idéia de que seu surgimento está ligado à agrimensura.”

“Mas que gregos teriam levado a geometria para a Grécia? Heródoto não diz nada sobre o assunto e estudiosos postularam, posteriormente, que teria sido Tales. Para tornar o relato mais consistente, afirmou-se que esse matemático teria calculado até mesmo a altura de uma das pirâmides do Egito. Tal anedota, que Eudemo e Proclus ajudaram a construir, combina a idéia de que a geometria prática, de origem egípcia, teria evoluído para a determinação indireta de medidas inacessíveis, caso da altura de uma pirâmide.”

“Não há uma documentação confiável que possa estabelecer a transição da matemática mesopotâmica e egípcia para a grega. Essa é, na verdade, uma etapa na construção do mito de que existiria uma matemática geral da humanidade.”

“A designação de ‘abstrato’ ganha, agora, um sentido diferente do exposto no Capítulo 1, já que aqui a expressão está associada à prática geométrica e não numérica. O registro grego é fragmentário e a escassez de fontes faz com que o trabalho do historiador pareça especulativo. Existem alguns tratados matemáticos concluídos, outros parcialmente finalizados e outros, ainda, com apenas trechos aleatórios preservados acidentalmente em obras derivadas, além de alguma literatura sobre a matemática em textos filosóficos.”

“Alguns termos de geometria já apareciam, por exemplo, na arquitetura. Há escritos técnicos do século VI abordando problemas relacionados à astronomia e ao calendário.”

“é difícil estabelecer as bases factuais desta e de outras afirmações sobre Tales atribuídas por Proclus a Eudemo. Na verdade, o papel de Tales foi objeto de algumas controvérsias históricas. Segundo W. Burkert, parece ser fato que, por volta do século V, seu nome era empregado em conexão com resultados geométricos. Além disso, Aristóteles menciona Tales na Metafísica como o fundador da filosofia.”

“A historiografia da matemática costuma analisar, entre as épocas de Tales e de Euclides, as contribuições da escola pitagórica do século V. Os ensinamentos dessa escola teriam influenciado um outro matemático importante desse século, Hipócrates de Quios. Além disso, é frequente encontrarmos referências a Pitágoras como um dos primeiros matemáticos gregos. Mas ambas as afirmações são hoje largamente questionadas pelos historiadores.”

“Se o matemático mais conhecido do século V, Hipócrates de Quios, não era herdeiro de Pitágoras, de onde veio sua matemática? As evidências mostram que havia uma matemática grega antes dos pitagóricos. Em meados desse século, tal prática parecia estar no centro dos interesses dos principais pensadores, pois muitos deles se conectavam com questões matemáticas, caso de Anaxágoras, Hípias e Antifonte. (…) Em Atenas, a geometria era ensinada, apesar de não sabermos exatamente como. Nos diálogos de Platão, há algumas evidências da existência de um ambiente de discussão sobre os problemas geométricos que data de uma época anterior a sua obra. Um exemplo são os diálogos entre Sócrates e Teodoro, que era contemporâneo de Hipócrates e de quem Teeteto, importante personagem dos textos de Platão, deve ter sido aluno.”

“como mostra W. Burkert, a escola pitagórica não parece ter tido um papel significativo na transformação da matemática de seu tempo. A convicção de que o pitagorismo está na fonte da matemática grega decorre da tradição educacional dos neopitagóricos e neoplatônicos da Antiguidade, durante os primeiros séculos da era cristã.” Curioso.

“Neste capítulo e no próximo mostraremos que a visão de que a matemática abstrata, que faz uso de demonstrações, foi uma invenção dos gregos toma por base os Elementos de Euclides. Logo, seria anacrônico analisar o desenvolvimento da matemática antes de Euclides a partir de inferências lógicas.”

“Mesmo o famoso teorema ‘de Pitágoras’, em sua compreensão geométrica como relação entre medidas dos lados de um triângulo retângulo, não parece ter sido particularmente estudado por Pitágoras e sua escola. Veremos, ainda, que a descoberta das grandezas incomensuráveis, freqüentemente atribuída a um pitagórico, deve ter tido outras origens. Tal descoberta contribuiu para a separação entre a geometria e a aritmética, a primeira devendo se dedicar às grandezas geométricas e a segunda, aos números – separação que é um dos traços marcantes da geometria grega, ao menos na maneira como ela se disseminou com Euclides.”

“Um de nossos principais objetivos, aqui, é desconstruir os mitos envolvidos na chamada ‘crise dos incomensuráveis’. Essa tese tem origem em obras já ultrapassadas que constituem um exemplo paradigmático de um modo de fazer história da matemática – hoje contestado – baseado em pressupostos modernos sobre a natureza dessa disciplina. As narrativas sobre o suposto escândalo provocado pela descoberta dos incomensuráveis citam também os paradoxos de Zenão, por isso descreveremos brevemente seus enunciados, mostrando que estes tinham um fim filosófico e não matemático.”

“A Antiuidade tardia nos legou 2 textos de pensadores neoplatônicos nos quais os feitos da matemática grega foram avaliados: um de Jâmblico, De communi mathematica scientia (Sobre o conhecimento matemático comum), e outro de Proclus, o primeiro prólogo ao seu Comentário sobre o primeiro livro dos Elementos de Euclides. Jâmblico viveu entre os séculos III e IV d.C. (…) De communi mathematica scientia é o terceiro volume de uma obra maior, dedicada ao pitagorismo, De vita pytaghorica (Sobre a vida pitagórica)” “A escassez das fontes, somada à convergência interessada dos únicos textos disponíveis, nos permite duvidar até mesmo da existência de um matemático de nome Pitágoras.”

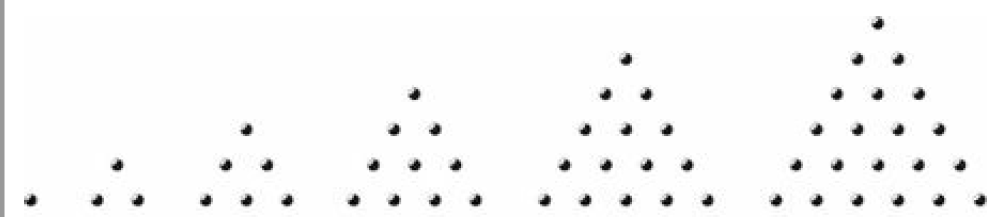

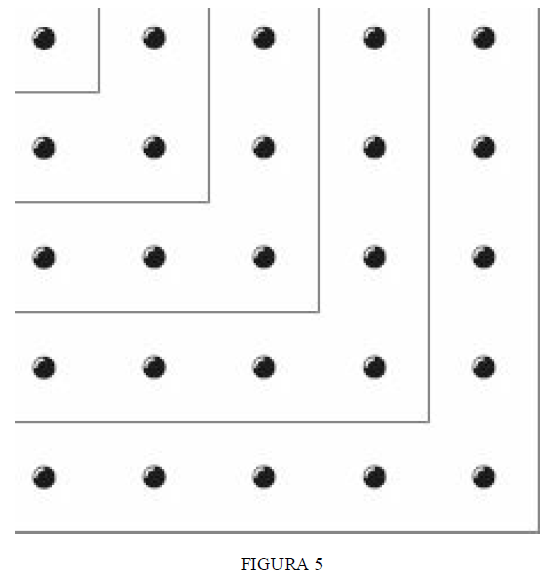

“A matemática atribuída a Pitágoras é a aritmética de pontinhos, que será detalhada adiante, mas não se sabe ao certo se ela é uma criação de um matemático chamado Pitágoras, de integrantes de uma escola antiga chamada pitagórica (mas não de Pitágoras), ou dos neoplatônicos e neopitagóricos da Antiguidade, como Jâmblico e Nicômaco.”

“Os pitagóricos embora sejam vistos como os primeiros a considerar o número do ponto de vista teórico, e não apenas prático, não possuíam, de fato, uma noção de número puro. Diferentemente de Platão, os pitagóricos não admitiam nenhuma separação entre número e corporeidade, entre seres corpóreos e incorpóreos.”

“O Um é ao mesmo tempo par e ímpar, ser bissexuado a partir do qual os outros números se desenvolveram. O par e o ímpar são elementos dos números e na conjugação limitado-ilimitado está a oposição cósmica primordial por trás do mundo, expresso em números.”

“As relações entre os números não representavam, portanto, uma cadeia linear na qual todas as relações internas eram semelhantes. Cada arranjo designava uma ordem distinta, com ligações próprias. Daí o papel dos números figurados na matemática pitagórica. Esses números eram, de fato, figuras formadas por pontos, como as que encontramos em um dado. Não é uma cifra, como 3, que serve de representação pictórica para um número, mas a delimitação de uma área constituída de pontos, como uma constelação.”

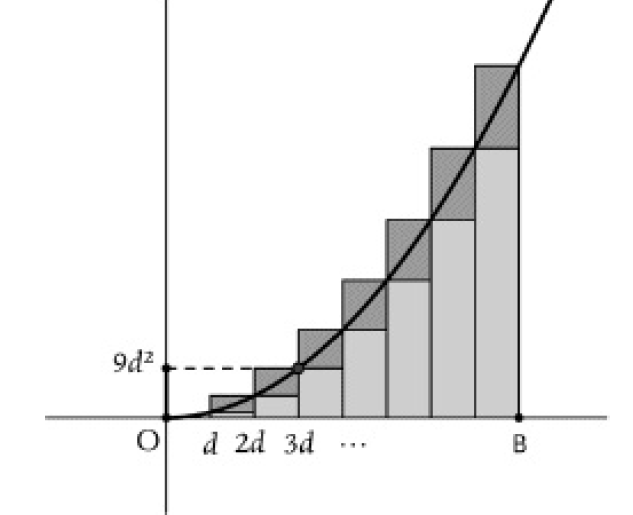

“Os números triangulares representados na Figura 1 podem ser associados aos nossos números 1, 3, 6, 10, 15 e 21, que possuem, respectivamente, ordem n = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 e 6. Em linguagem atual, o número triangular de ordem n é dado pela soma da progressão aritmética 1 + 2 + 3 + … + n = [n*(n+1)]/2. Em seguida, temos os números quadrados, que, em nosso simbolismo, podem ser escritos como n².”

Essa imagem, chamada gnomons, é a representação pitagórica equivalente à nossas equações:

1² + 3 = 2²

2² + 5 = 3²

3² + 7 = 4² (4º gnomon, etc.)

“Temos notícia de que a ciência matemática era dividida, primeiramente, em duas partes: uma que tratava dos números; outra, das grandezas. Cada uma era subdividida em duas outras partes: a aritmética estudava as quantidades em si mesmas; a música, as relações entre quantidades; a geometria, as grandezas em repouso; e a astronomia, as grandezas em movimento inerente. O conhecimento sobre esse aspecto da doutrina pitagórica vem da Metafísica de Aristóteles”

“Ar. usava essa tabela de opostos para criticar a separação binária platônica segundo a qual, de um lado, temos o igual, imóvel e harmônico e, de outro, o desigual, movente e desarmônico.” Que pena que não se encontre isso em lugar nenhum do cânone platônico!

“Para Aristóteles, isso indicaria a presença de seres abstratos. Por exemplo, a partir do tetractys [o terceiro triângulo de duas imagens acima, aquele com 10 pontos] os pitagóricos teriam obtido as entidades abstratas: ponto, reta, plano e sólido. No entanto, Burkert nota que essa tese está em franca contradição com outra afirmação do próprio Aristóteles, a saber, que não havia entre os pitagóricos a noção de ponto, no sentido geométrico do termo.”

“O enunciado mais famoso associado ao nome de Pitágoras é o teorema que estabelece uma relação entre as medidas dos lados de um triângulo retângulo: <O quadrado da hipotenusa é igual à soma dos quadrados dos catetos>. Hoje se sabe que essa relação era conhecida por diversos povos mais antigos do que os gregos e pode ter sido um saber comum na época de Pitágoras. No entanto, não é nosso objetivo mostrar que os pitagóricos não foram os primeiros na história a estabelecer tal relação. O objetivo é investigar de que modo esse resultado podia intervir na matemática praticada pelos pitagóricos, com as características anteriormente descritas. A demonstração desse teorema, encontrada nos Elementos de Euclides, faz uso de resultados que eram desconhecidos na época da escola pitagórica. Não se conhece nenhuma prova do teorema geométrico que tenha sido fornecida por um pitagórico e parece pouco provável que ela exista.”

“Não deve ter havido um teorema geométrico sobre o triângulo retângulo demonstrado pelos pitagóricos, e sim um estudo das chamadas triplas pitagóricas. O problema das triplas pitagóricas é fornecer triplas constando de dois números quadrados e um terceiro número quadrado que seja a soma dos dois primeiros.¹ Essas triplas são constituídas por números inteiros que podem ser associados às medidas dos lados de um triângulo retângulo.

¹ Alguns historiadores da matemática defendem que na placa Plimpton 322 há um indício de que os babilônios já estudavam as triplas pitagóricas, o que mostraria que a relação atribuída a Pitágoras seria conhecida na Babilônia pelo menos mil anos antes dele. Essa tese é questionada por E. Robson em ‘Neither Sherlock Holmes nor Babylon: A reassessment of Plimpton 322’ e ‘Words and pictures: new light on Plimpton 322’.”

“Provavelmente, os pitagóricos chegaram a essas triplas por meio do gnomon”

“a primeira tripla pitagórica: (3, 4, 5).” = 3² + 4² = 5²

“Na tradição, poucas triplas são mencionadas e (3, 4, 5) tem um papel especial, pois 3 é o macho; 4, a fêmea; e 5, o casamento que os une no triângulo pitagórico. Segundo Proclus, havia 2 métodos para se obter triplas pitagóricas: um de Pitágoras, outro de Platão. O primeiro começa pelos números ímpares. Associando um dado número ao menor dos lados do triângulo que formam o ângulo reto, tomamos o seu quadrado, subtraímos a unidade e dividimos por 2, obtendo o outro lado, que forma o ângulo reto. Para obter o lado oposto, somamos a unidade novamente ao resultado. Seja 3, por exemplo, o menor dos lados. Toma-se o seu quadrado e subtrai-se a unidade, obtendo 8, e extrai-se a metade de 8, que é 4. Adicionando a unidade novamente, obtemos 5, e o triângulo retângulo que procuramos é o de lados 3, 4 e 5.

O método platônico começa por um número par, considerado um dos lados que formam o ângulo reto. Primeiro dividimos esse número por 2 e fazemos o quadrado de sua metade. Subtraindo 1 desse quadrado, obtemos o outro lado que forma o ângulo reto e, adicionando 1, o lado restante. Por exemplo, seja 4 o lado. Dividimos por 2 e tomamos o quadrado da metade, obtendo 4. Subtraímos 1 e adicionamos 1, obtendo os lados restantes: 3 e 5.” Em linguagem moderna, o método platônico = (2a)² + (a² − 1)² = (a² + 1)².

“Logo, pelo contexto em que esse resultado intervém, não é possível dizer que o conhecimento aritmético das triplas pitagóricas seja o exato correlato do teorema geométrico atribuído a Pitágoras, daí as aspas empregadas aqui ao falarmos do teorema <de Pitágoras>.”

“A versão mais popular é a de que esse livro de Euclides resulta de uma compilação de conhecimentos matemáticos anteriores, ainda que a forma da exposição deva ser característica do tempo e do meio em que ele viveu. Não é possível confirmar essa tese, mas é fato que uma boa parte da matemática contida nessa obra associa-se a outros trabalhos gregos. Euclides apresenta 2 tipos de teoria das razões e proporções. Há uma versão no livro VII que pode ser aplicada somente à razão entre inteiros e é atribuída aos pitagóricos. A definição contida aí é usada para razões entre grandezas comensuráveis. A segunda versão, presumidamente posterior à primeira, está no livro V e é atribuída ao matemático platônico Eudoxo. Essa última teoria das razões e proporções é bastante sofisticada e se aplica igualmente a grandezas comensuráveis e incomensuráveis.”

“Segundo Knorr, o desenvolvimento formal da matemática deve ter se iniciado com os trabalhos de Teeteto, no início do século IV”

“Hipócrates teria sido o autor da primeira obra escrita em um livro de ‘elementos’, ou seja, com a apresentação sistemática da geometria. Infelizmente, poucos fragmentos sobreviveram. Seu trabalho mais conhecido é o estudo das lúnulas, que são porções de círculo compreendidas entre duas circunferências, incluindo a investigação de quadraturas. Os escritos de Hipócrates constituem o único documento do século V contendo um estudo de razões e proporções entre figuras geométricas. Ele sabia que a razão entre as áreas de dois segmentos de círculo semelhantes é igual à razão entre os quadrados de seus diâmetros. Essa demonstração, de uma época bem anterior à de Eudoxo, exigia um conhecimento profundo de razões e proporções.”

“A palavra antifairese vem do grego e significa, literalmente, subtração recíproca. Na álgebra moderna, o procedimento é semelhante ao conhecido como <algoritmo de Euclides> e sua função é encontrar o maior divisor comum entre dois números.”

“O método da antifairese descreve uma série de comparações. Por exemplo, podemos pedir a um aluno que compare duas pilhas de pedras. Se a primeira tem 60 e a segunda, 26, concluímos que:

1) da primeira pilha com 60 pedras é possível subtrair duas vezes a pilha com 26 pedras, e ainda resta uma pilha com 8 pedras;

2) da pilha com 26 pedras é possível subtrair três vezes a pilha com 8 pedras, e ainda resta uma pilha com 2 pedras;

3) por fim, a pilha com 2 pedras cabe, exatamente, quatro vezes na pilha com 8 pedras.

A sequência <2x, 3x e 4x exatamente> representa o número de subtrações que se pode fazer em cada passo. Podemos chamá-la de razão e usar a notação Ant (60, 26) = [2, 3, 4] para representar a razão antifairética 60:26. A escolha de grandezas que permitem uma representação finita por números inteiros nem sempre é possível.

Para Fowler, os gregos entendiam a razão 22:6, por exemplo, baseados no fato de que é possível subtrair 6 de 22 três vezes, restando 4; em seguida, subtrai-se 4 de 6, restando 2; finalmente, subtrai-se 2 de 4 exatamente duas vezes. Logo, a razão 22:6 seria definida pela sequência <3x, 1x, 2x>.”

“Essa antifairese equivale a fazer A = n0B + R1, em seguida, B = n1R1 + R2, depois R2 = n1R2 + R3, e assim por diante. O procedimento pode ou não chegar ao fim. Quando ele termina, a medida comum aos dois segmentos fica associada a um terceiro segmento, R, que é o último resto não-nulo encontrado e que mede os segmentos A e B. Isso permite achar a medida comum a 2 segmentos e, assim, é possível reduzir a geometria à aritmética, pois cada segmento será representado por sua medida.”

“A teoria das grandezas comensuráveis foi desenvolvida, primeiramente, pela aritmética e, depois, por imitação, pela geometria. Por essa razão, ambas as ciências definem grandezas comensuráveis como aquelas que estão uma para outra na razão de um número para outro número, o que implica que a comensurabilidade existiu primeiro entre os números.” Proclus

“Como afirma Fowler, essa técnica teria sido usada para desenvolver uma teoria de razão independente da noção de proporção. Segundo o historiador, 3 noções distintas de razão estariam presentes na tradição grega: uma vinda da teoria musical; outra, da astronomia (que teria servido de base para as definições do livro V dos Elementos); e uma terceira, baseada na antifairese.”

“Se temos, por exemplo, um quadrado de lado 1, esse lado não é comensurável em comprimento com a diagonal. No entanto, seu quadrado 1 é comensurável com o quadrado da diagonal, que é 2. É lícito dizer, então, que essas grandezas são comensuráveis em potência.”

“as teses atuais sugerem que houve um desenvolvimento contínuo da matemática, e não uma ruptura, antes e depois do momento em que se percebeu a possibilidade de duas grandezas serem incomensuráveis.”

“Reza a lenda que a descoberta dos irracionais causou tanto escândalo entre os gregos que o pitagórico responsável por ela, Hípaso, foi expulso da escola e condenado à morte. Não se sabe de onde veio essa história, mas parece pouco provável que seja verídica. Em um artigo publicado em 1945, ‘The discovery of incommensurability by Hippasos of Metapontum’ (A descoberta da incomensurabilidade por Hípaso de Metaponto), Von Fritz conjectura que a incomensurabilidade tenha sido descoberta durante o estudo do problema das diagonais do pentágono regular, que constituem o famoso pentagrama. A lenda da descoberta dos irracionais por Hípaso foi erigida a partir desse exemplo. Entretanto, os historiadores que seguimos aqui contestam tal reconstrução, uma vez que ela implica o uso de fatos geométricos elaborados que só se tornaram conhecidos depois dos Elementos de Euclides.”

“Não sabemos exatamente qual a importância da geometria na escola pitagórica, mas acredita-se que não tenha sido tão relevante quanto a aritmética. Para os pitagóricos, que praticavam aritmética com números representados por pedrinhas e estavam preocupados com teorias sobre o cosmos, resumidas pelo enunciado <tudo é número>, a descoberta da incomensurabilidade não deve ter tido nenhuma importância. A teoria dos números desenvolvida por eles e a matemática abstrata, associada à geometria, estavam em dois planos distintos: <tudo é número> não significava <todas as grandezas são comensuráveis>.”

“A afirmação de que a descoberta da incomensurabilidade produziu uma crise nos fundamentos da matemática grega foi consolidada por trabalhos de historiadores da 1ª metade do século XX. P. Tannery já havia afirmado que tal descoberta significou um escândalo lógico na escola pitagórica do século V, sendo mantida em segredo inicialmente, até que, ao se tornar conhecida, teve como efeito desacreditar o uso das proporções na geometria. Um dos artigos mais influentes a propalar a ocorrência de uma crise foi ‘Die Grundlagenkrisis der griechischen Mathematik’ (A crise dos fundamentos da matemática grega), de Hasse & Scholz, publicado em 1928, que fazia referência somente à possibilidade de ter havido uma crise dos fundamentos da matemática grega.”

“O problema da incomensurabilidade parece ter surgido no seio da própria matemática, mais precisamente da geometria, sem a relevância filosófica que lhe é atribuída. Ao contrário da célebre lenda, os historiadores citados, como Burkert e Knorr, contestam até mesmo que essa descoberta tenha representado uma crise nos fundamentos da matemática grega. Não se encontra alusão a escândalo em nenhuma passagem dos escritos a que temos acesso e que citam o problema dos incomensuráveis, como os de Platão ou Aristóteles. Aristóteles, aliás, não cita o problema dos incomensuráveis nem mesmo em sua crítica aos pitagóricos.”

“Em ‘Impact of modern mathematics on ancient mathematics’ (Impacto da matemática moderna sobre a matemática antiga), Knorr interpreta as diferentes versões da crise dos incomensuráveis que dominaram a historiografia em meados do século XX como um sinal da influência de pressupostos filosóficos. Os estudos meta-matemáticos do período foram marcados pelo questionamento em relação aos fundamentos da matemática, associado aos trabalhos de Dedekind, Cantor e Hilbert. A tentação de ver nos gregos uma crise análoga era um modo de valorizar os trabalhos do início do século XX, encarados como soluções para dilemas não resolvidos por 2500 anos.”

“É provável que a antifairese entre o lado e a diagonal do quadrado fosse conhecida de modo geométrico nos séculos V e IV sem que se atribuísse ao procedimento o valor de uma demonstração da incomensurabilidade. Outra hipótese sobre a descoberta da incomensurabilidade, dessa vez no contexto da aritmética, tem sua origem em um resultado atribuído a Euclides. No final do século IV, Aristóteles se refere à prova da incomensurabilidade em sua exposição sobre a técnica de raciocínio por absurdo, dizendo que: se o lado e o diâmetro são considerados comensuráveis um em relação ao outro, pode-se deduzir que os números ímpares são iguais aos pares; essa contradição afirma, portanto, a incomensurabilidade das duas grandezas.” “Mas a demonstração desse fato faz uso de uma linguagem algébrica que não poderia ter sido usada pelos gregos antigos.” Ar., gênio, mas sempre menino bobo!

“Na matemática grega anterior a Euclides, os problemas geométricos eram tratados como se fossem cálculos com números. Foi justamente a descoberta dos incomensuráveis que provocou uma separação entre os universos das grandezas e dos números. A demonstração pré-euclidiana da incomensurabilidade não pode ter se servido, portanto, dessa separação. Logo, a prova encontrada nesse apêndice deve ser tardia e com certeza não foi por meio dela que se descobriu a incomensurabilidade.”

“Por volta do ano 375, Platão criticou os geômetras por não empregarem critérios de rigor desejáveis para as práticas matemáticas. Não por acaso o trabalho de Eudoxo se desenvolveu no seio da academia platônica. Sendo assim, ainda que não possamos dizer que a transformação dos fundamentos da matemática grega é devida a Platão, este expressa o descontentamento dos filósofos com os métodos adotados pela matemática e articula o trabalho dos pensadores à sua volta para que se dediquem a formalizar as técnicas utilizadas indiscriminadamente.”

“Temos notícia dos paradoxos de Zenão por fontes indiretas, como a Física de Aristóteles, e seus objetivos estão expostos no diálogo Parmênides de Platão. Tais paradoxos são mencionados algumas vezes em conexão com o problema dos incomensuráveis. No entanto, os argumentos de Zenão se voltam contra pressupostos filosóficos. Além disso, a descoberta da incomensurabilidade deve ter se dado depois da época de Zenão, o que nos leva a concluir que seus paradoxos nada têm a ver com a questão. Em livros de história da matemática, é comum também relacionar esses paradoxos ao desenvolvimento do cálculo infinitesimal e do conceito de limite. Trata-se, no entanto, de uma interpretação a posteriori.”

“O pensamento dos eleatas busca ultrapassar a percepção e fundamentar a filosofia em bases não-empíricas. A filosofia do Uno nega veementemente a possibilidade de que as coisas possam ser subdivididas, já que essa divisão implica a constituição de uma pluralidade. Zenão queria mostrar, com seus paradoxos, que é absurdo considerar não apenas que as coisas são infinitamente divisíveis, mas também que são compostas de infinitos indivisíveis. Os paradoxos dizem respeito à impossibilidade do movimento, no caso de admitirmos quaisquer dessas hipóteses. § Esses paradoxos contra o movimento só são conhecidos na forma exposta por Aristóteles, com o objetivo de refutá-los. Nenhum argumento matemático é usado em sua contestação.” Ainda o mesmo dos pseudo-divulgadores científicos de hoje: ‘Olha só, um físico afirmou que o tempo não existe!!’

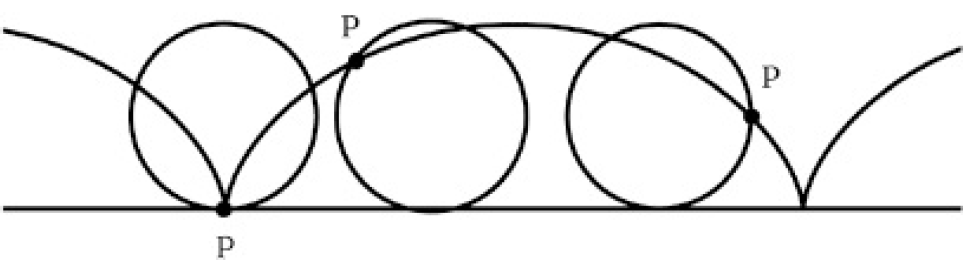

“A série que pode ser usada para traduzir o problema de Zenão é ½ + (½)² + (½)³ cuja soma deve ser igual a 1.”

Demonstração moderna:

0,999999… = 0,9 + 0,09 + … = 9/10 + 9/100 + 9/1000 + … = 9/10 / (1 – 1/10) = ½ / (1 – ½) = 1

Resumindo todo o teor do capítulo:

A historiografia calibrada recente nos ensina que:

Pitágoras é o Pai da matemática indutiva grega;

Euclides é o Pai da matemática dedutiva grega. (Pai – conhecido! – da Axiomática)

“Por que então o método dedutivo teria sido empregado na matemática grega e quais as causas da adoção da noção de prova? § Problemas matemáticos complexos começaram a surgir por volta do quinto e quarto séculos, como o de expressar o comprimento da diagonal em termos do lado de um quadrado. Esse não era somente um problema ainda não-resolvido, era um problema que desafiava a percepção, além de não poder ser abordado somente por meio de cálculos. A lógica matemática e a prova dedutiva podem ir além do que é perceptível.”

“Por um lado, os matemáticos tinham de lidar com a complexidade e o caráter abstrato de alguns problemas que contradiziam a intuição e não eram acessíveis por meio de cálculos. Por outro, a organização em escolas, cujo objetivo era transmitir o conhecimento matemático da época, pode ter gerado uma demanda pela compilação e sistematização desse conhecimento. A necessidade de colocar em ordem a aritmética e a geometria herdadas das tradições mais antigas, bem como as descobertas recentes, deve ter levado, naturalmente, a um questionamento sobre a forma de expor o conteúdo matemático.”

Tudo que é abstrato se cimenta no ar.

“Uma das primeiras evidências diretas e extensas sobre a geometria grega no período aqui considerado, para além de fragmentos ou reconstruções tardias, é o diálogo platônico intitulado Mênon, que se supõe tenha sido escrito por volta do ano 385 a.C.” Minha tradução de trechos (os matemáticos sempre em verde): https://seclusao.art.blog/2020/01/22/menon-ou-da-virtude-ou-da-inexistencia-de-uma-ciencia-politica-ultima-traducao-do-ciclo-platao-obras-completas-virginia-woolf-ao-final/.

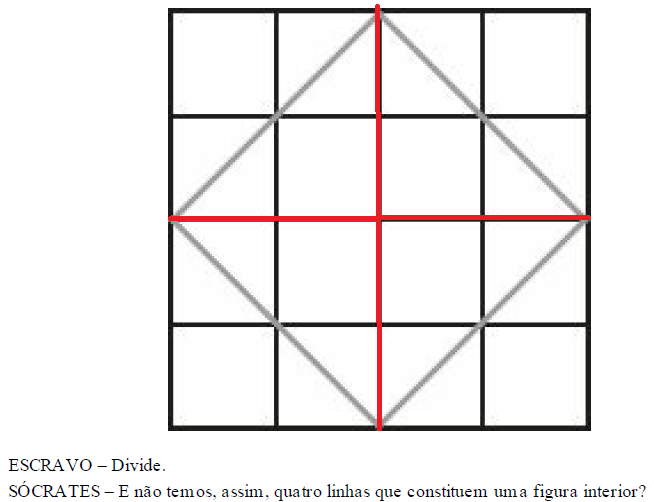

Sem que minha tradução fosse prejudicada por isso, fi-la da seguinte forma (linhas vermelhas), ao passo que Sócrates na verdade se referia às linhas cinzentas (acontece que essa era uma forma de demonstrar a incomensurabilidade da diagonal do quadrado numa forma bidimensional, enquanto que na minha tradução aludi ao cubo, tridimensional, em nota de rodapé):

Com efeito, eis o quadrado de oito pés de área, a olho nu. A palavra diagonal não aparece no texto, apenas lado. Porque a diagonal é, afinal, um lado de outro quadrado, justaposto.

“A pergunta sobre quanto mede a diagonal não chega nem mesmo a ser evocada, talvez porque Sócrates saiba que essa medida não pode ser encontrada no universo dos números admitidos até então. Mas, além disso, talvez ele quisesse apresentar ao escravo um novo tipo de conhecimento, no qual basta exibir a linha sobre a qual o quadrado deve ser construído.”

Vemos que embora minha intenção fosse diferente da da autora (Tatiana Roque), não discordamos nada a respeito do diálogo (a evidenciação do conceito de reminiscência X o correto ensino da matemática geométrica, em que pese a ‘irracionalidade do número da diagonal’). É que em algum momento ambas as coisas são uma só na exposição de Sócrates. O que fica evidente no meu trecho comentado que reproduzo aqui: “Este raciocínio todo, bem simples, serve para lembrar, também: não é todo matemático que é bom em ensinar matemática. É preciso saber o método para não fazer o aluno <descobrir a natureza> da forma indesejada (pelo ensino oficial, pelos livros, pelo próprio educador, etc.). Mostrar que o jovem se equivocava ao imaginar o quadrado e que se daria conta do erro ao contar os quadrados após desenhar o quadrado na areia favorecia Sócrates na discussão que tinha com Mênon (sobre a teoria da reminiscência).” O que mostra, ainda, o quão visual era, àquela altura, a matemática para os gregos!

Mas continuando…

“A geometria, tal como a conhecemos atualmente, lida com formas abstratas. Um quadrado não é o quadrado que desenhamos no papel; é uma forma abstrata, a forma <quadrado>. Os objetos geométricos de base – como o ponto, a reta e o plano – também não são concretos. O ponto é algo sem dimensão, que não existe na realidade. Logo, esses objetos só podem ser concebidos por meio de uma abstração.” Parênteses filosóficos importantes: a idéia platônica é só isso: a verdade não está no fenômeno! Aristóteles, tão genial em suas sistematizações, não foi capaz de compreendê-lo. Ao contrário das aparências, não foi seu melhor aluno… Ou, não importa: enquanto aluno presencial, na Academia, talvez até tenha sido. Mas nós somos alunos muito melhores neste século! Em nenhum momento se tratava de criar duplos metafísicos, mas de descrever o Um parmenídeo.

O conhecimento não são sombras, mas também não é o sol ou qualquer imagem tridimensional fora da caverna (precaução contra a hiper-fenomenologia)…

“A matemática parte sempre de primeiros princípios: um conjunto de hipóteses a partir das quais se poderá descer até as conclusões, que constituirão o conhecimento científico. Nesse processo, objetos sensíveis se fazem necessários, o que é muito claro na matemática: raciocinar sobre um quadrado hipotético exige o emprego do desenho de um quadrado no quadro-negro, ainda que saibamos que esse quadrado desenhado não é o verdadeiro quadrado. A dialética é um conhecimento de tipo distinto, que usa as hipóteses como ponto de partida para um mundo acima delas, no qual não há hipóteses.” Nessa última frase serei obrigado a discordar: Platão nunca fez essa distinção. Todo transcender ao que está por trás das aparências, o verdadeiro, ainda é sempre um exercício de engatinhar e tatear por entre hipóteses…

“Entre as ciências hipotéticas, a geometria é o principal exemplo usado por Platão. Essa ciência utiliza hipóteses e dados sensíveis para chegar a conclusões de modo consistente. Um de seus traços distintivos é o fato de utilizar formas visíveis com o fim, somente, de investigar o absoluto que encerram. Quando um geômetra pesquisa as propriedades de um quadrado desenhado no quadro-negro – cópia do quadrado ideal –, é o verdadeiro quadrado que ele pretende simular e não meramente a sua cópia. As verdades da Idéia só podem ser vistas com os olhos do pensamento, e em sua busca a alma é obrigada a usar os primeiros princípios, descendendo destes suas conseqüências.” Agora se expressou melhor!

“A OBRA Elementos, de Euclides, é vista como o ápice do esforço de organização da geometria grega desenvolvida até o século III a.C. Por um lado, afirma-se que seria somente uma compilação de resultados já existentes produzidos por outros, o que torna o seu autor um mero editor. Por outro, celebra-se que esses trabalhos tenham sido expostos de um modo novo, o que revelaria a predominância na Grécia, nessa época, de um pensamento lógico e dedutivo.”

CAPÍTULO 3. Problemas, teoremas e demonstrações na geometria grega

“Os Elementos de Euclides são um conjunto de 13 livros publicados por volta do ano 300, mas não temos registros da obra original, somente versões e traduções tardias.”

“Do ponto de vista histórico, cabe perguntar até que ponto o padrão que esse livro exprime era realmente preponderante na matemática que se desenvolveu antes e depois de Euclides. Além disso, é fato, as construções propostas nessa obra são efetuadas por meio da régua e do compasso. Mas seria essa restrição decorrente de uma proibição de outros métodos de construção? Teria essa determinação afetado toda a geometria depois de Euclides?” “Um dos objetivos deste capítulo é relativizar a tese da influência platônica na reorganização da geometria, bem como o papel das técnicas de construção propostas nos Elementos no contexto das práticas gregas de resolução de problemas.”

“Todo enunciado universal sobre um objeto geométrico é um teorema geométrico. Os problemas são um primeiro passo para passarmos do mundo prático à geometria. (…) Grande parte da crença que temos na motivação platônica de Euclides decorre da utilização dos Comentários de Proclus. A Coleção matemática de Pappus é outra das principais fontes de conhecimento dos trabalhos matemáticos gregos, cujos registros originais se perderam.”

“A resolução de problemas geométricos envolve sempre uma construção, e o critério usado nessa classificação baseia-se nos tipos de linhas necessárias para efetuá-la. Além da régua e do compasso, são listados métodos que usam cônicas e curvas mecânicas, como a quadratriz, a espiral e o conchóide de Nicomedes, conhecidos antes do fim do século III. As construções com régua e compasso não permitem resolver todos os problemas propostos pelos matemáticos gregos antes e depois de Euclides, que não se furtavam, por isso, a utilizar outros métodos.”

“A visão de que os matemáticos gregos se aferravam aos fundamentos e a padrões rígidos tem origem na história da matemática desenvolvida na virada dos séculos XIX e XX, período marcado por pesquisas sobre o rigor da matemática dessa época. O objetivo dos trabalhos de Hilbert, por exemplo, era justamente fundamentar a geometria euclidiana. Mas será que os matemáticos da Antiguidade eram tão preocupados assim com questões de fundamento quanto os do final do século XIX?”

“Nos primeiros livros dos Elementos, muitos resultados parecem pertencer a uma tradição que podemos chamar de ‘cálculo de áreas’, que inclui a transformação de uma área em outra equivalente, bem como a soma de áreas. Veremos que as proposições dos livros I e II podem ser entendidas a partir dessas práticas, incluindo o teorema sobre a hipotenusa do triângulo retângulo,

dito ‘de Pitágoras’.”

“Arquimedes nasceu mais ou menos no momento em que Euclides morreu, em torno da segunda década do século III. Era de esperar, portanto, que o trabalho de Euclides tivesse uma influência marcante em sua obra. Mas não foi bem assim. Arquimedes não pode ser visto como sucessor de Euclides; e seu trabalho não se inscreve, por assim dizer, em uma tradição euclidiana. Um exemplo disso é a utilização de métodos mecânicos de construção, caso da espiral de Arquimedes.”

“Entre os diversos problemas matemáticos clássicos difundidos antes de Euclides estão o da duplicação do cubo (problema deliano) e o da quadratura do círculo.”

“Há diversas construções para as meias proporcionais que datam de períodos posteriores e podem ser encontradas em Três excursões pela história da matemática, de J.B. Pitombeira. Entre elas está a de Menecmo, que viveu por volta de 350 e foi aluno de Eudoxo. O seu conhecimento da teoria das razões e proporções permitia concluir, sem usar equações, que o ponto que satisfaz o problema das meias proporcionais é a interseção de duas cônicas, uma parábola e uma hipérbole, que atualmente seriam dadas, respectivamente, pelas equações y² = bx e xy = ab.”

“Por valorizar a matemática teórica, Platão teria desprezo pelas construções mecânicas, realizadas com ferramentas de verdade. A régua e o compasso, apesar de serem instrumentos de construção, podem ser representados, respectivamente, pela linha reta e pelo círculo, figuras geométricas com alto grau de perfeição.” “é coerente dizer que sua filosofia encarava a reta e o círculo como figuras geométricas superiores, mas também não há, em seus escritos, indicações explícitas de imposição dessas figuras como protótipos para toda a geometria, nem de proibição do uso de outras construções.”

OS CHATÕES DOS 1800! “O responsável por creditar a Platão a restrição à régua e ao compasso é o matemático alemão Hermann Hankel, que atuou na segunda metade do século XIX e trabalhou com matemáticos como Weierstrass e Kronecker, conhecidos pela preocupação com os fundamentos da matemática. Em 1874, Hankel publicou um texto histórico sobre a geometria euclidiana – Zur Geschichte der Mathematik in Alterthum und Mittelalter (Sobre a história da matemática na Idade Média e na Antiguidade) – contendo extrapolações com base em trechos da obra de Platão. Em uma tese meticulosa sobre o papel da restrição à régua e ao compasso escrita em 1936, mas que continua uma referência sobre o nascimento desse mito, o alemão A.D. Steele analisa por que a tese de Hankel é falsa e fornece algumas hipóteses sobre as razões do uso exclusivo desses instrumentos nos Elementos de Euclides. Referimo-nos especificamente aos Elementos, pois a restrição à régua e ao compasso não parece ser importante nem mesmo em outros escritos de Euclides.”

“Quer optemos pela motivação pedagógica ou por essa segunda razão, de cunho epistemológico, parece mais adequado entender a exclusividade da régua e do compasso nos Elementos como uma restrição pragmática cujo objetivo poderia ser apresentar um uso ótimo dos instrumentos mais simples possíveis.”

“O tipo de organização dos Elementos também é objeto de extensas pesquisas, pois os resultados dos primeiros livros não são necessariamente os mais antigos, ou seja, a obra não é organizada de modo cronológico. Acredita-se que os livros VII a IX – os livros aritméticos dos Elementos, atribuídos aos pitagóricos – sejam os mais antigos. Os livros II, III e IV não apresentam uma ordem seqüencial tão nítida quanto a dos livros I, V e VI, o que pode indicar que aqueles sejam anteriores a esses. Além disso, nos livros I a IV, as construções e provas são realizadas por métodos de congruência e pelo cálculo de áreas e não empregam razões e proporções, que já eram conhecidas muito antes de Euclides. Isso poderia ser um indício de que eles teriam sido escritos depois da descoberta dos incomensuráveis, que demandou uma nova teoria das razões e proporções. A partir desse momento, parece ter havido uma reorganização do conhecimento geométrico. A exposição de resultados envolvendo semelhança de figuras, por exemplo, que já eram bastante antigos, foi adiada para depois do livro V, uma vez que necessitava de uma teoria geral das razões e proporções para grandezas (incluindo as incomensuráveis).”

“Um traço particular dos Elementos é que as grandezas são tratadas enquanto tais e jamais são associadas a números (ao contrário, nos livros sobre números, eles são tratados como segmentos de reta).” “Alguns pesquisadores, como Fowler, afirmam que o livro V dos Elementos, que contém uma teoria das razões e proporções, trata de resultados mais recentes do que os outros livros.

Resumindo, podemos traçar a seguinte cronologia: os livros VII a IX, que seriam os mais antigos, empregam uma linguagem ingênua de razões e proporções que estaria presente desde épocas muito remotas, antes da descoberta dos incomensuráveis; os livros I a IV tratam de resultados sobre equivalência de áreas também antigos, mas as demonstrações evitam o uso de razões e proporções; no livro V é apresentada a nova teoria das razões e proporções, servindo de base para o estudo de equivalência de áreas e semelhança de figuras de um novo modo, o que é feito no livro VI. Além disso, o livro I teria sido escrito com o intuito de apresentar os princípios, por isso exibiria um cuidado especial com o encadeamento das proposições.”

“Uma definição é um tipo de hipótese da qual o aprendiz não tem uma noção evidente, mas faz uma concessão àquele que as ensina e aceita-a sem demonstração. As definições que iniciam os Elementos fazem referência aos objetos matemáticos que serão utilizados ao longo da obra e que possuem um conteúdo intuitivo.”

“Livro I – Definições

1. Ponto é aquilo de que nada é parte

2. E linha é comprimento sem largura

3. E extremidades de uma linha são pontos

4. E linha reta é a que está posta por igual com os pontos sobre si mesma

5. E superfície é aquilo que tem somente comprimento e largura

6. E extremidades de uma superfície são retas

…

10. E quando uma reta, tendo sido alteada sobre uma reta, faça os ângulos adjacentes iguais, cada um dos ângulos é reto, e a reta que se alteou é chamada uma perpendicular àquela sobre a qual se alteou

…

15. Círculo é uma figura plana contida por uma linha (que é chamada circunferência), em relação à qual todas as retas que a encontram (até a circunferência do círculo), a partir de um ponto dos postos no interior da figura, são iguais entre si

…”

“Na definição 4, o termo linha reta designa o que hoje chamamos de segmento de reta. À maneira de Euclides, usaremos aqui o termo reta com esse sentido.” “A definição 15 está na origem da distinção entre círculo e circunferência encontrada em alguns livros-texto atuais.”

“Uma noção comum, segundo Proclus, é um enunciado de conteúdo óbvio, tido facilmente como válido pelo aprendiz. Se além de o enunciado ser desconhecido ele é proposto como verdadeiro por meio de alguma argumentação temos um postulado. Nesse caso, é necessário que aquele que ensina convença o aprendiz de sua validade.”

“Livro I – Postulados

1. Fique postulado traçar uma reta a partir de todo ponto até todo ponto

2. Também prolongar uma reta limitada, continuamente, sobre uma reta

3. E, com todo centro e distância, descrever um círculo

4. E serem iguais entre si todos os ângulos retos

5. E, caso uma reta, caindo sobre duas retas, faça os ângulos interiores e do mesmo lado menores do que dois retos, sendo prolongadas as duas retas, ilimitadamente, encontrarem-se no lado no qual estão os menores do que dois retos

Livro I – Noções comuns

1. As coisas iguais à mesma coisa são também iguais entre si

2. E, caso sejam adicionadas coisas iguais a coisas iguais, os todos são iguais

3. E, caso de iguais sejam subtraídas iguais, as restantes são iguais

4. E, caso iguais sejam adicionadas a desiguais, os todos são desiguais

…

8. E o todo é maior do que a parte

9. E duas retas não contêm uma área”

“Os enunciados da matemática seguem-se, por demonstração, dos primeiros princípios. Essa é a definição do método axiomático-dedutivo. Mas por que Euclides usou esse método?”

“Como vimos, o objetivo da proposição I-45 é mostrar como se pode construir um paralelogramo, com ângulo dado, cuja área seja igual à de um polígono qualquer. Observemos que essa construção torna possível representar a área de qualquer polígono como um retângulo, uma vez que o retângulo é um caso particular de paralelogramo, com ângulos retos. Para entender a importância dessa construção, é preciso saber como eram realizados os cálculos de áreas na geometria grega.

Atualmente, medir é associar uma grandeza a um número. Se quisermos somar as áreas de dois polígonos, teremos de calcular a área de cada um, por meio de uma fórmula, e somar os resultados (que são números). Mas nesse momento as grandezas não eram tratadas por meio de associação a números.”

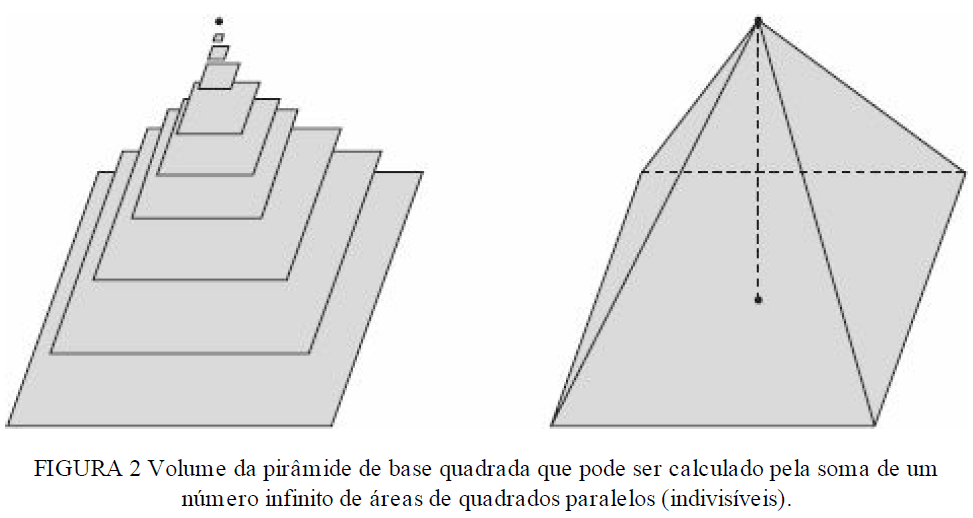

“para ‘medir’ a área de uma figura qualquer, deveríamos encontrar uma figura simples cuja área fosse igual à da figura dada. Essa figura simples era um quadrado. Logo, o problema de encontrar a quadratura de uma figura qualquer era equivalente ao problema de construir um quadrado cuja área fosse igual à da figura dada.”

“Os primeiros princípios servem, portanto, à demonstração dos primeiros resultados, que, em seguida, efetuarão o papel de premissas para novas demonstrações. O encadeamento dedutivo das proposições pode ser compreendido, assim, como a busca de uma espécie de economia na argumentação.”

“se 2 triângulos têm 2 lados iguais e os ângulos formados por eles também iguais, então os triângulos são congruentes. O uso do termo ‘congruente’ é bem mais recente e tem como objetivo resolver uma inconsistência lógica colocada pela formalização posterior da geometria euclidiana. Na lógica, o princípio da identidade afirma que uma coisa só é igual a si mesma. Portanto, 2 triângulos ou 2 figuras geométricas quaisquer não podem ser iguais. Daí o emprego do termo ‘congruente’, que significa, intuitivamente, que 2 figuras podem ser colocadas uma em cima da outra.” A lógica não é sempre lógica.

“se 2 triângulos ABC e DBC possuem a mesma base e o terceiro vértice em uma paralela à base, então eles têm áreas iguais. Atualmente, dizemos que 2 triângulos têm áreas iguais se possuem a mesma base e a mesma altura, uma vez que a área é calculada pela fórmula bh/2.Como tratamos aqui de uma tradição geométrica que não associava grandezas a números, não se mediam a base e a altura para calcular a área. A proposição I-38 procura dizer em que casos duas áreas são equivalentes sem que seja preciso calculá-las. Ora, se o 3º vértice de 2 triângulos está em uma paralela à base, eles possuem as mesmas alturas. Como é dado que as bases são iguais, eles têm também a mesma área. As 2 últimas proposições do livro I são justamente o resultado conhecido como teorema ‘de Pitágoras’ e o seu recíproco.”

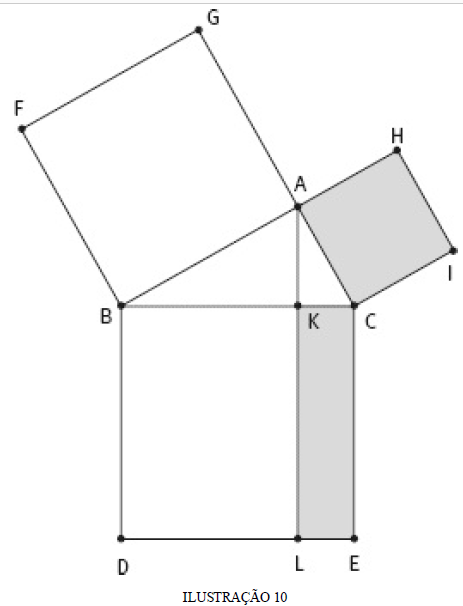

“Proposição I-47

Nos triângulos retângulos, o quadrado sobre o lado que se estende sob o ângulo reto é igual aos quadrados sobre os lados que contêm o ângulo reto. [mal-redigido pra porra, como veremos mais abaixo!]

Demonstração: Seja o triângulo retângulo ABC, com ângulo reto BAC. Queremos mostrar que a área do quadrado construído sobre o lado BC é igual à soma das áreas dos quadrados construídos sobre os lados AB e AC, que formam o ângulo reto BAC. Vamos ilustrar a demonstração com figuras que não foram usadas por Euclides, [não fosse isso e dificilmente entenderíamos] mas manteremos o espírito de sua prova. Descrevemos sobre cada lado um quadrado e vamos mostrar que a área do quadrado construído sobre o lado BC pode ser obtida pela soma de 2 retângulos, um deles com área igual à do quadrado construído sobre AB (em cor branca na Ilustração 10) e o outro com área igual à do quadrado construído sobre AC (de cor cinza).

“Queremos mostrar que a área do quadrado ABFG é igual à do retângulo BDLK. Os próximos passos para concluir essa demonstração são os seguintes:

1. Mostrar que a área do triângulo ABF, que é metade do quadrado ABFG, é igual à área do triângulo DBK, que é metade da do retângulo BDLK.

2. Para isso, mostraremos que a área de ABF é igual à de CBF e que a área de DBK é igual à de ABD.

3. Como já mostramos que a área de ABD e de CBF são iguais, concluiremos que a área de ABF é igual à área de DBK, assim, a área do quadrado ABFG será igual à do retângulo BDLK.

Como os ângulos BAC e BAG são retos, os segmentos CA e AG estão sobre uma mesma reta. Como essa reta é paralela a BF, temos que CBF e ABF são triângulos de mesma base com o 3º vértice em uma paralela a essa base. Logo, pela proposição I-38, eles possuem a mesma área. De modo análogo, como AL foi construída paralelamente a BD, temos que ABD e DBK são triângulos de mesma base com 3º vértice em uma paralela à base, sendo assim, possuem a mesma área. Esse parágrafo, juntamente com o anterior, conclui a etapa 2.”

“Encontrar a ‘quadratura’ significava, no contexto grego, achar a área de uma figura dada. Usando essa proposição, como seria possível, portanto, comparar as áreas de dois retângulos sem calculá-las? Basta construir os quadrados com áreas iguais às dos retângulos e comparar os lados. E como podemos somar as áreas de dois retângulos? Basta construir os quadrados com áreas iguais às dos retângulos e somar as áreas desses quadrados por meio do teorema ‘de Pitágoras’.”