Dumas [pai]

25/01/16-24/09/16

GLOSSÁRIO

Frascati: vinho branco italiano, procedente da região de mesmo nome

mazzolata: também mazzatello. Punição capital extremamente cruel empregada pela Igreja no século XVIII. A arma usada pelo carrasco era um enorme martelo ou um machado. O executor, no caso da 1ª arma, embalava a arma para pegar impulso no único golpe que desferia e acertava na cabeça do condenado, que se não morria caía desmaiado no chão e depois tinha a garganta cortada. Reservado a crimes hediondos.

singlestick: foi modalidade olímpica em 1904

“I have a partner, and you know the Italian proverb – Chi ha compagno ha padrone – <He who has a partner has a master.>”

“<but you were right to return as soon as possible, my boy.>

<And why?>

<Because Mercedes is a very fine girl, and fine girls never lack followers; she particularly has them by dozens.>

<Really?> answered Edmond, with a smile which had in it traces of slight uneasiness.”

“Believe me, to seek a quarrel with a man is a bad method of pleasing the woman who loves that man.”

“Why, when a man has friends, they are not only to offer him a glass of wine, but moreover, to prevent his suwallowing 3 or 4 pints [2 litros] of water unnecessarily!”

“<Well, Fernand, I must say,> said Caderousse, beginning the conversation, with that brutality of the common people in which curiosity destroys all diplomacy, <you look uncommonly like a rejected lover;> and he burst into a hoarse laugh”

“<they told me the Catalans were not men to allow themselves to be supplanted by a rival. It was even told me that Fernand, especially, was terrible in his vengeance.>

Fernand smiled piteously. <A lover is never terrible,> he said.”

“pricked by Danglars, as the bull is pricked by the bandilleros”

“<Unquestionably, Edmond’s star is in the ascendant, and he will marry the splendid girl – he will be captain, too, and laugh at us all unless.> – a sinister smile passed over Danglars’ lips – <unless I take a hand in the affair,> he added.”

“happiness blinds, I think, more than pride.”

“That is not my name, and in my country it bodes ill fortune, they say, to call a young girl by the name of her betrothed, before he becomes her husband. So call me Mercedes if you please.”

“We are always in a hurry to be happy, Mr. Danglars; for when we have suffered a long time, we have great difficulty in believing in good fortune.”

“<I would stab the man, but the woman told me that if any misfortune happened to her betrothed, she would kill herself>

<Pooh! Women say those things, but never do them.>”

“<you are 3 parts drunk; finish the bottle, and you will be completely so. Drink then, and do not meddle with what we are discussing, for that requires all one’s wit and cool judgement.>

<I – drunk!> said Caderousse; <well that’s a good one! I could drink four more such bottles; they are no bigger than cologne flanks. Pere Pamphile, more wine!>”

and Caderousse rattled his glass upon the table.”

“Drunk, if you like; so much the worse for those who fear wine, for it is because they have bad thoughts which they are afraid the liquor will extract from their hears;”

“Tous les mechants sont beuveurs d’eau; C’est bien prouvé par le deluge.”

“Say there is no need why Dantes should die; it would, indeed, be a pity he should. Dantes is a good fellow; I like Dantes. Dantes, your health.”

“<Absence severs as well as death, and if the walls of a prison were between Edmond and Mercedes they would be as effectually separated as if he lay under a tombstone.>

<Yes; but one gets out of prison,> said Caderousse, who, with what sense was left him, listened eagerly to the conversation, <and when one gets out and one’s name is Edmond Dantes, one seeks revenge>-“

“<I say I want to know why they should put Dantes in prison; I like Dantes; Dantes, our health!>

and he swallowed another glass of wine.”

“the French have the superiority over the Spaniards, that the Spaniards ruminate, while the French invent.”

“Yes; I am supercargo; pen, ink, and paper are my tools, and whitout my tools I am fit for nothing.” “I have always had more dread of a pen, a bottle of ink, and a sheet of paper, than of a sword or pistol.”

“<Ah,> sighed Caderousse, <a man cannot always feel happy because he is about to be married.>”

“Joy takes a strange effect at times, it seems to oppress us almost the same as sorrow.”

“<Surely,> answered Danglars, <one cannot be held responsible for every chance arrow shot into the air>

<You can, indeed, when the arrow lights point downward on somebody’s head.>”

“<That I believe!> answered Morrel; <but still he is charged>-

<With what?> inquired the elder Dantes.

<With being an agent of the Bonapartist faction!>

Many of our readers may be able to recollect how formidable such and accusation became in the period at which our story is dated.”

“the man whom 5 years of exile would convert into a martyr, and 15 of restoration elevate to the rank of a god.”

“glasses were elevated in the air à l’Anglais, and the ladies, snatching their bouquets from their fair bossoms, strewed the table with their floral treasures.”

“yes, yes, they could not help admitting that the king, for whom we sacrificed rank, wealth and station was truly our <Louis the well-beloved,> while their wretched usurper has been, and ever wil be, to them their evil genius, their <Napoleon the accursed.>”

“Napoleon is the Mahomet of the West and is worshipped as the personification of equality.”

“one is the quality that elevantes [Napoleon], the other is the equality that degrades [Robespierre]; one brings a king within reach of the guillotine, the other elevates the people to a level with the throne.”

9 Termidor: degolação de Robespierre, num 27/7

4/4/14 – Queda de Napoleão

“<Oh, M. de Villefort,>, cried a beautiful young creature, daughter to the Comte de Salvieux, and the cherished friend of Mademoiselle de Saint-Meran, <do try and get up some famous trial while we are at Marseilles. I never was in a law-cout; I am told it is so very amusing!>

<Amusing, certainly,> replied the young man, <inasmuch as, instead of shedding tears as at a theatre, you behold in a law-court a case of real and genuine distress – a drama of life. The prisoner whom you there see pale, agitated, and alarmed, instead of – as is the case when a curtain falls on a tragedy – going home to sup peacefully with his family, and then retiring to rest, that he may recommence his mimic woes on the morrow, – is reconducted to his prison and delivered up to the executioner. I leave you to judge how far your nerves are calculated to bear you through such a scene. Of this, however, be assured, that sould any favorable apportunity present itself, I will not fail to offer you the choice of being present.>”

“I would not choose to see the man against whom I pleaded smile, as though in mockery of my words. No; my pride is to see the accused pale, agitated and as though beaten out of all composure by the fire of my eloquence.”

“Why, that is the very worst offence they could possibly commit, for, don’t you see, Renée, the king is the father of his people, and he who shall plot or contrive aught against the life and safety of the parent of 32 millions of souls, is a parricide upon a fearfully great scale.>”

“It was, as we have said, the 1st of March, and the prisoner was soon buried in darkness.” 01/03/16

“But remorse is not thus banished; like Virgil’s wounded hero, he carried the arrow in his wound, and, arrived at the salon, Villefort uttered a sigh that was almost a sob, and sank into a chair.”

“Danglars was one of those men born with a pen behind the ear, and an inkstand in place of a heart. Everything with him was multiplication or subtraction. The life of a man was to him of far less value than a numeral, especially when, by taking it away, he could increase the sum total of his own desires. He went to bed at his usual hour, and slept in peace.”

A BARCA DO INFERNO QUE ARCA COM AS CONSEQÜÊNCIAS DO PE(S)CADO

desejos desejados no mar infinito

despojos desejosos de ser entregues aos derrotados

de consolo

que nojo

dessa raça

em desgraça

perpétua

que a maré a leve

para o fundo

do abismo

pesadâncora

pesadume

pesado cardume

proa perdeu o lume

popa nasceu sem gume

mastro adubado de petróleo

fóssil agora

apagado e insolente

eu sou experiente, experimente!

um louco que está sempre no lucro

das questões eu chego ao fulcro

por mais que não seja inteligente,

seja só uma compulsão demente

ser verdadeiro

se ver como herdeiro

de uma civilização

legada ao esquecimento

divino

o trem metafísico e seu lote de vagãos pagãos

levando à conclusão

de que o choque é elétrico

e anafilático

nada de milagre nada de intangível

só cobramos e debitamos o crível

(02/03/16)

“said Louis XVIII, laughing; <the greatest captains of antiquity amused themselves by casting pebbles [seixos] into the ocean – see Plutarch’s Scipio Africanus.>”

“<So then,> he exclaimed, turning pale with anger, <seven conjoined and allied armies overthrew that man. A miracle of heaven replaced me on the throne of my fathers after five-and-twenty years of exile. I have, during those 5-&-20 years, spared no pains to understand the people of France and the interests which were confided to me; and now when I see the fruition of my wishes almost within reach, the power I hold in my hands bursts, and shatters me to atoms!>”

“Really impossible for a minister who has an office, agents, spies, and fifteen hundred thousand [1,5 million] francs for secret service money, to know what is going on at 60 leagues from the coast of France!”

“Why, my dear boy, when a man has been proscribed by the mountaineers, has escaped from Paris in a hay-cart, been hunted over the plains of Bordeaux by Robespierre’s bloodhounds, he becomes accustomed to most things.”

“<Come, come,> said he, <will the Restoration adopt imperial methods so promptly? Shot, my dear boy? What an idea! Where is the letter you speak of? I know you too well to suppose you would allow such a thing to pass you.>”

“Quando a polícia está em débito, ela declara que está na pista; e o governo pacientemente aguarda o dia em que ela vem para dizer, com um ar fugitivo, que perdeu a pista.”

“The king! I thought he was philosopher enough to allow that there was no murder in politics. In politics, my dear fellow, you know, as well as I do, there are no men, but ideas – no feelings, but interests; in politics we do not kill a man, we only remove an obstacle, that is all. Would you like to know how matters have progressed? Well, I will tell you. It was thought reliance might be placed in General Quesnel; he was recommended to us from the Island of Elba; one of us went to him, and visited him to the Rue Saint-Jacques, where he would find some friends. He came there, and the plan was unfolded to him for leaving Elba, the projected landing, etc. When he had heard and comprehended all to the fullest extent, he replied that he was a royalist. Then all looked at each other, – he was made to take an oath, and did so, but with such an ill grace that it was really tempting Providence to swear him, and yet, in spite of that, the general allowed to depart free – perfectly free. Yet he did not return home. What could that mean? why, my dear fellow, that on leaving us he lost his way, that’s all. A murder? really, Villefort, you surprise me.”

<The people will rise.>

<Yes, to go and meet him.>

“Ring, then, if you please, for a second knife, fork, and plate, and we will dine together.”

“<Eh? the thing is simple enough. You who are in power have only the means that money produces – we who are in expectation, have those which devotion prompts.>

<Devotion!> said Villefort, with a sneer.

<Yes, devotion; for that is, I believe, the phrase for hopeful ambition.>

And Villefort’s father extended his hand to the bell-rope to summon the servant whom his son had not called.”

“Say this to him: <Sire, you are deceived as to the feeling in France, as to the opinions of the towns, and the prejudices of the army; he whom in Paris you call the Corsican ogre, who at Nevers is styled the usurper, is already saluted as Bonaparte at Lyons, and emperor at Grenoble. You think he is tracked, pursued, captured; he is advancing as rapidly as his own eagles. The soldiers you believe to be dying with hunger, worn out with fatigue, ready to desert, gather like atoms of snow about the rolling ball as it hastens onward. Sire, go, leave France to its real master, to him who acquired it, not by purchase, but by right of conquest; go, sire, not that you incur any risk, for your adversary is powerful enough to show you mercy, but because it would be humiliating for a grandson of Saint Louis to owe his life to the man of Arcola Marengo, Austerlitz.> Tell him this, Gerard; or, rather, tell him nothing. Keep your journey a secret; do not boast of what you have come to Paris to do, or have done; return with all speed; enter Marseilles at night, and your house by the back-door, and there remain quiet, submissive, secret, and, above all, inoffensive”

“Every one knows the history of the famous return from Elba, a return which was unprecedented in the past, and will probably remain without a counterpart in the future.”

“Napoleon would, doubtless, have deprived Villefort of his office had it not been for Noirtier, who was all powerful at court, and thus the Girondin of ‘93 and the Senator of 1806 protected him who so lately had been his protector.” “Villefort retained his place, but his marriage was put off until a more favorable opportunity.” “He made Morrel wait in the antechamber, although he had no one with him, for the simple sreason that the king’s procureur always makes every one wait, and after passing a quarter of an hour in reading the papers, he ordered M. Morrel to be admitted.”

“<Edmond Dantes.>

Villefort would probably have rather stood opposite the muzzle of a pistol at five-and-twenty paces than have heard this name spoken; but he did not blanch.”

“<Monsieur,> returned Villefort, <I was then a royalist, because I believed the Bourbons not only the heirs to the throne, but the chosen of the nation. The miraculous return of Napoleon has conquered me, the legitimate monarch is he who is loved by his people.>”

“<There has been no arrest.>

<How?>

<It is sometimes essential to government to cause a man’s disappearance without leaving any traces, so that no written forms or documents may defeat their wishes.>

<It might be so under the Bourbons, but at present>-

<It has always been so, my dear Morrel, since the reign of Louis XIV. The emperor is more strict in prison discipline than even Louis himself>”

“As for Villefort, instead of sending to Paris, he carefully preserved the petition that so fearfully compromised Dantes, in the hopes of an event that seemed not unlikely, – that is, a 2nd restoration. Dantes remained a prisoner, and heard not the noise of the fall of Louis XVIII’s throne, or the still more tragic destruction of the empire.” “At last there was Waterloo, and Morrel came no more; he had done all that was in his power, and any fresh attempt would only compromise himself uselessly.”

“But Fernand was mistaken; a man of his disposition never kills himself, for he constantly hopes.”

“Old Dantes, who was only sustained by hope, lost all hope at Napoleon’s downfall. Five months after he had been separated from his son, and almost at the hour of his arrest, he breathed his last in Mercedes’ arms.”

“The inspector listened attentively; then, turning to the governor, observed, <He will become religious – he is already more gentle; he is afraid, and retreated before the bayonets – madmen are not afraid of anything; I made some curious observations on this at Charenton.> Then, turning to the prisoner, <What is it you want?> said he.”

“<My information dates from the day on which I was arrested,> returned the Abbé Faria; <and as the emperor had created the kingdom of Rome for his infant son, I presume that he has realized the dream of Machiavelli and Caesar Borgia, which was to make Italy a united kingdom.>

<Monsieur,> returned the inspector, <providence has changed this gigantic plan you advocate so warmly.>

<It is the only means of rendering Italy strong, happy, and independent.>

<Very possibly; only I am not come to discuss politics, but to inquire if you have anything to ask or to complain of.>

<The food is the same as in other prisons, – that is, very bad, the lodging is very unhealthful, but, on the whole, passable for a dungeon; but it is not that which I wish to speak of, but a secret I have to reveal of the greatest importance.>

<It is for that reason I am delighted to see you,> continued the abbé, <although you have disturbed me in a most important calculation, which, if it succeded, would possibly change Newton’s system. Could you allow me a few words in private.>”

“<On my word,> said the inspector in a low tone, <had I not been told beforehand that this man was mad, I should believe what he says.>”

“A new governor arrived; it would have been too tedious to acquire the names of the prisoners; he learned their numbers instead. This horrible place contained 50 cells; their inhabitants were designated by the numbers of their cell, and the unhappy young man was no longer called Edmond Dantes – he was now number 34.”

Prisioneiros de segurança máxima não devem adoecer – que bactéria ou vírus cosmopolita os visitaria? Que mudança que fosse mais forte e sensível que o supertédio?

“he addressed his supplications, not to God, but to man. God is always the last resource. Unfortunates, who ought to begin with God, do not have any hope in him till they have exhausted all other means of deliverance.”

“Dantes spoke for the sake of hearing his own voice; he had tried to speak when alone, but the sound of his voice terrified him.”

“in prosperity prayers seem but a mere medley of words, until misfortune comes and the unhappy sufferer first understands the meaning of the sublime language in which he invokes the pity of heaven!”

“<Yes, yes,> continued he, <’Twill be the same as it was in England. After Charles I, Cromwell; after Cromwell, Charles II, and then James II, and then some son-in-law or relation, some Prince of Orange, a stadtholder¹ who becomes a king. Then new concessions to the people, then a constitution, then liberty. Ah, my friend!> said the abbé, turning towards Dantes, and surveying him with the kindling gaze of a prophet, <you are young, you will see all this come to pass.>”

¹ Magistrado de província holandesa

“<But wherefore are you here?>

<Because in 1807 I dreamed of the very plan Napoleon tried to realize in 1811; because, like Napoleon, I desired to alter the political face of Italy, and instead of allowing it to be split up into a quantity of petty principalities, each held by some weak or tyrannical ruler, I sought to form one large, compact and powerful empire; and lastly, because I fancied I had found Caesar Borgia in a crowned simpleton, who feigned to enter into my views only to betray me. It was the plan of Alexander VI, but it will never succeed now, for they attempted it fruitlessly, and Napoleon was unable to complete his work. Italy seems fated to misfortune.> And the old man bowed his head.

Dantes could not understand a man risking his life for such matters. Napoleon certainly he knew something of, inasmuch as he had seen and spoken with him; but of Clement VII and Alexander VI he knew nothing.

<Are you not,> he asked, <the priest who here in the Chateau d’If is generally thought to be – ill?>

<Mad, you mean, don’t you?>

<I did not like to say so,> answered D., smiling.”

“In the 1st place, I was 4 years making the tools I possess, and have been 2 years scraping and digging out earth, hard as granite itself; then what toil and fatigue has it not been to remove huge stones I should once have deemed impossible to loosen.”

“Another, other and less stronger than he, had attempted what he had not had sufficient resolution to undertake, and had failed only because of an error in calculation.”

“<When you pay me a visit in my cell, my young friend,> said he, <I will show you an entire work, the fruits of the thoughts and reflections of my whole life; many of them meditated over in the Colosseum at Rome, at the foot of St. Mark’s columm at Venice, little imagining at the time that they would be arranged in order within the walls of the Chateau d’If. The work I speak is called ‘A Treatise on the Possibility of a General Monarchy in Italy,’ and will make one large quarto volume.>”

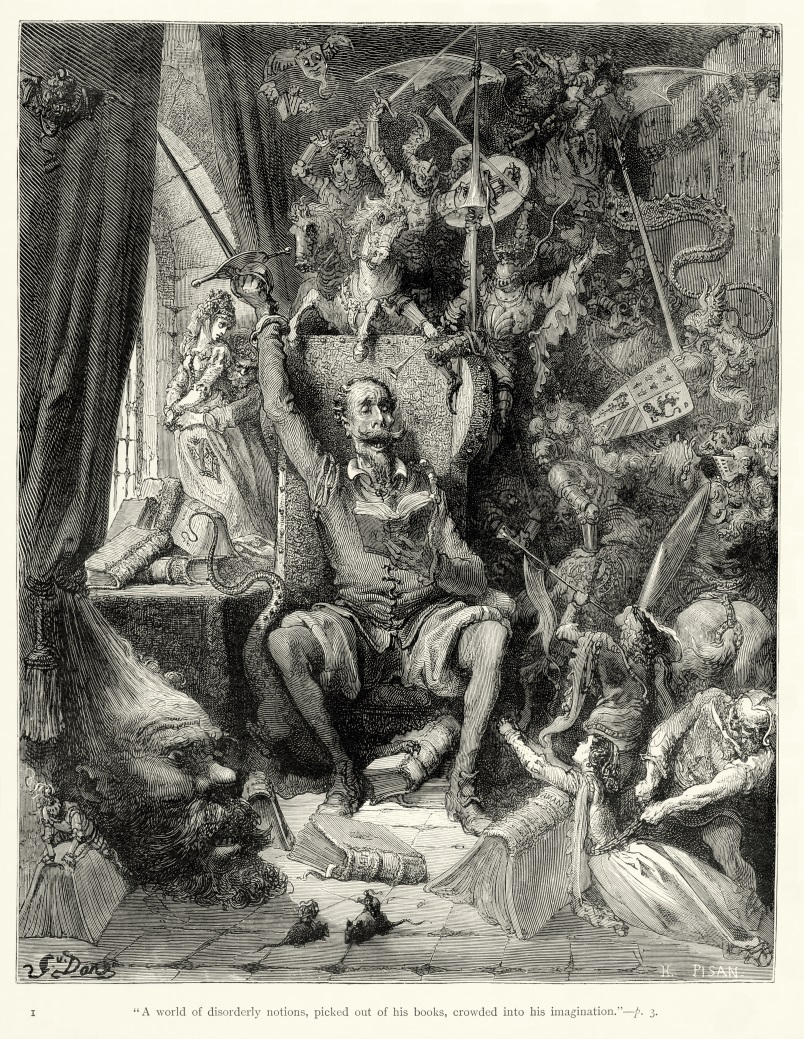

“I had nearly 5.000 volumes in my library at Rome; but after reading them over many times, I found out that with 150 well-chosen books a man possesses if not a complete summary of all human knowledge, at least all that a man need really know. I devoted 3 years of my life to reading and studying these 150 volumes, till I knew them nearly by heart; so that since I have been in prison, a very slight effort of memory has enabled me to recall their contents as readily as though the pages were open before me. I could recite you the whole of Thucidides, Xenophon, Plutarch, Titus Livius, Tacitus, Strada, Jornandes [Jordanes], Dante, Montaigne, Shakespeare, Spinoza, Machiavelli, and Bossuet.”

“Yes, I speak 5 of the modern tongues – that is to say, German, French, Italian, English and Spanish; by the aid of ancient Greek I learned modern Greek – I don’t speak so well asI could wish, but I am still trying to improve myself.” “Improve yourself!” repeated Dantes; “why, how can you manage to do so?”

“This last explanation was wholly lost upon Dantes, who had always imagined, from seeing the sun rise from behind the mountains and set in the Mediterranean, that it moved, and not the earth. A double movement of the globo he inhabited, and of which he could feel nothing, appeared to him perfectly impossible.”

“Should I ever get out of prison and find in all Italy a printer courageous enough to publish what I have composed, my literary reputation is forever secured.”

“What would you not have accomplished if you had been free?”

“Possibly nothing at all; the overflow of my brain would probably, in a state of freedom, have evaporated in a 1,000 follies; misfortune is needed to bring to light the treasure of the human intellect. Compression is needed to explode gunpowder. Captivity has brought my mental faculties to a focus”

“<if you visit to discover the author of any bad action, seek first to discover the person to whom the perpetration of that bad action could be in any way advantageous. Now, to apply it in your case, – to whom could your disappearance have been serviceable?>

<To no one, by heaven! I was a very insignificant person.>

<Do not speak thus, for your reply evinces neither logic nor philosophy; everything is relative, my dear young friend, from the king who stands in the way of his successor, to the employee who keeps his rival out of a place. Now, in the event of the king’s death, his successor inherits a crown, – when the employee dies, the supernumerary steps into his shoes, and receives his salary of 12.000 livres. Well, these 12.000 livres are his civil list, and are as essential to him as 12.000.000 of a king. Every one, from the highest to the lowest degree, has his place on the social ladder, and is beset by stormy passions and conflicting interests, as in Descartes’ theory of pressure and impulsion.” efeito borboleta parte I “But these forces increase as we go higher, so that we have a spiral which in defiance of reason rests upon the apex and not on the base.”

“<Simply because that accusation had been written with the left hand, and I have noticed that> –

<What?>

<That while the writing of different persons done with the right hand varies, that performed with the left hand is invariably uniform.>”

“That is in strict accordance with the Spanish character; an assassination they will unhesitatingly commit, but an act of cowardice never.”

“Pray ask me whatever questions you please; for, in good truth, you see more clearly into my life than I do myself.”

“<About six or seven and twenty years of age, I should say.>

<So,> anwered the abbé. <Old enough to be ambitious, but too young to be corrupt. And how did he treat you?>”

“<That alters the case. Tis man might, after all, be a greater scoundrel than you have thought possible>

<Upon my word,> said Dantes, <you make me shudder. Is the world filled with tigers and crocodiles?>

<Yes; and remember that two-legged tigers and crocodiles are more dangerous than the others.>”

“Had a thunderbolt fallen at the feet of D., or hell opened its yawining gulf before him, he could not have been more completely transfixed with horror than he was at the sound of these unexpected words. Starting up he clasped his hands around his head as though to prevent his very brain from bursting, and exclaimed, <His father! his father!>”

“D. was at lenght roused from his revery by the voice of Faria, who, having also been visited by his jailer, had come to invite his fellow-sufferer to share his supper. The reputation of being out of his mind though harmlessly and even amusingly so, had procured for the abbé unusual privileges. He was supplied with bread of a finer whiter quality than the usual prison fare, and even regaled each Sunday with a small quantity of wine.”

“The elder prisoner was one of those persons whose conversation, like that of all who have experienced many trials, contained many usefel and important hints as well as sound information; but it was never egotistical, for the unfortunate man never alluded to his own sorrows. D. listened with admiring attention to all he said; some of his remarks corresponded with what he already knew, or applied to the sort of knowledge his nautical life had enabled him to acquire.”

“I can well believe that so learned a person as yourself would prefer absolute solitude to being tormented with the company of one as ignorant and uninformed as myself.”

“The abbé smiled: <Alas, my boy,> said he, <human knowledge is confined within very narrow limits; and when I have taught you mathematics, physics, history, and the 3 or 4 modern languages with which I am acquainted, you will know as much as I do myself. Now, it will scarcely require 2 years for me to communicate to you the stock of learnings I possess.>”

“<Not their application, certainly, but their principles you may; to learn is not to know; there are the learners and the learned. Memory makes the one, philosophy the other.>

<But cannot one learn philosophy?>

<Philosophy cannot be taught; it is the application of the sciences to truth; it is like the golden cloud in which the Messiah went up into heaven.>”

“An that very evening the prisoners sketched a plan of education, to be entered upon the following day. D. possessed a prodigious memory, combined with an astonishing quickness and readiness of conception; the mathematicla turn of his mind rendered him apt at al all kinds of calculation, while his naturally poetical feelings threw a light and pleasing veil over the dry reality of arithmetical computation, or the rigid severity of geometry. He already knew Italian, and had also picked up a little of the Romaic dialect during voyages to the East; and by the aid of these 2 languages he easily comprehended the construction of all the others, so that at the end of 6 months he began to speak Spanish, English, and German. In strict accordance with the promise made to the abbé, D. spoke no more of escape. Perhaps the delight his studies afforded him left no room for such thoughts; perhaps the recollection that he had pledged his word (on which his sense of honor was keen) kept him from referring in any way to the possibilities of flight. Days, even months, passed by unheeded in one rapid and instructive course. At the end of a year D. was a new man. D. observed, however, that Faria, in spite of the relief his society afforded, daily grew sadder; one thought seemed incessantly to harass and distract his mind. Sometimes he would fall into long reveries, sigh heavily and involuntarily, then suddenly rise, and, with folded arms, begin pacing the confined space of his dungeon. One day he stopped all at once, and exclaimed, <Ah, if there were no sentinel!>”

“Esse tesouro, que deve corresponder a dois… de coroas romanas no mais afastado a… da segunda abertura co… declara pertencer a ele som… herdeiro. <25 de Abril, 149-”

“Eu ouvi freqüentemente a frase <Tão rico como um Spada.>” “Ali, no 20º capítulo de a Vida do Papa Alexandre VI, constavam as seguintes linhas, que jamais poderei esquecer: – <As grandes guerras da Romagna terminaram; César Bórgia, que completou suas conquistas, precisava de dinheiro para adquirir a Itália inteira. O papa também precisava de dinheiro para liquidar seus problemas com Luís XII, Rei da França, que ainda era formidável a despeito de seus recentes reveses; e era necessário, portanto, recorrer a algum esquema rentável, o que era um problema de grande dificuldade nas condições de pauperização de uma exausta Itália. Sua santidade teve uma idéia. Ele resolveu fazer dois cardeais.

Ao escolher duas das maiores personagens de Roma, homens especialmente ricos – esse era o retorno pelo qual o pai santíssimo esperava. Primeiramente, ele poderia vender as grandes posições e esplêndidos ofícios que os cardeais já possuíam; e depois ele teria ainda dois chapéus para vender. Havia um terceiro ponto em vista, que logo aparecerá na narrativa. O papa e César Bórgia primeiro acharam os dois futuros cardeais; eles eram Giovanni Rospigliosi, que portava 4 das mais altas dignidades da Santa Sé; e César Spada, um dos mais nobres e ricos da nobreza romana; ambos sentiram a alta honraria de tal favor do papa. Eles eram ambiciosos, e César Bórgia logo encontrou compradores para suas posições. O resultado foi que Rospigliosi e Spada pagaram para ser cardeais, e 8 outras pessoas pagaram pelos ofícios que os cardeais tinham ante sua elevação; destarte 800.000 coroas entraram nos cofres dos especuladores.

É tempo agora de proceder à última parte da especulação. O papa encheu Rospigliosi e Spada de atenções, conferiu-lhes a insígnia do cardinalato, e os induziu a organizar seus negócios de forma a se mudarem para Roma. É aí que o papa e César Bórgia convidam os dois cardeais para jantar. Esse era um problema de disputa entre o santo pai e seu filho. César pensava que eles poderiam se utilizar de um dos meios que ele sempre tinha preparado para os amigos, i.e., em primeiro lugar, a famosa chave que era dada a certas pessoas com o pedido de que fossem e abrissem o armário equivalente. Essa chave era dotada de uma pequena ponta de ferro, – uma negligência da parte do chaveiro. Quando ela era pressionada a fim de abrir-se o armário, do qual a fechadura era complicada, a pessoa era picada por essa pontinha, e morria no dia seguinte. Havia também o anel com a cabeça de leão, que César usava quando queria cumprimentar seus amigos com um aperto de mão. O leão mordia a mão do assim favorecido, e ao cabo de 24h, a mordida se mostrava mortal. César propôs ao seu pai, que ou eles deveriam pedir aos cardeais para abrir o armário, ou apertar suas mãos; mas Alexandre VI respondeu: <Quanto aos valongos cardeais, Spada e Rospigliosi, convidemo-los para jantar, algo me diz que conseguiremos esse dinheiro de volta. Além disso, esquece-te, ó César, que uma indigestão se declara imediatamente, enquanto uma picada ou uma mordida ocasionam um atraso de um dia ou dois.> César recuou de tão convincente raciocínio, e os cardeais foram conseqüentemente chamados para jantar.

A mesa foi servida num vinhedo pertencente ao papa, perto de San Pierdarena, um retiro encantador que os cardeais conheciam de ouvir falar. Rospigliosi, bem disposto graças a suas novas dignidades, chegou com um bom apetite e suas maneiras mais obsequiosas. Spada, um homem prudente, e muito apegado a seu único sobrinho, um jovem capitão da mais alta promessa, pegou papel e caneta, e redigiu seu testamento. E depois mandou avisar o seu sobrinho para esperá-lo próximo ao vinhedo; mas aparentemente o servo não foi capaz de encontrá-lo.

Spada sabia o que esses convites significavam; desde a Cristandade, tão eminentemente civilizada, se alastrou por toda Roma, não era mais um centurião que vinha da parte do tirano com uma mensagem, <César quer que você morra.> mas era um núncio apostólico a latere, que vinha com um sorriso nos lábios para dizer, pelo papa, que <Sua santidade solicita sua presença num jantar.>

Spada se dirigiu lá pelas 2 a San Pierdarena. O papa o esperava. A primeira imagem a atrair a atenção de Spada foi a do seu sobrinho, todo paramentado, e César Bórgia cativando-o com as atenções mais marcadas. Spada empalideceu quando César o fitou com ar irônico, o que provava que ele havia antecipado tudo, e que a armadilha já estava em funcionamento.

Eles começaram a jantar e Spada foi capaz de indagar, somente, de seu sobrinho se ele tinha recebido sua mensagem. O sobrinho respondeu que não; compreendendo perfeitamente o significado da pergunta. Era tarde demais, já que ele já tinha tomado um copo de um excelente vinho, selecionado para ele expressamente pelo copeiro do papa. Spada testemunhou ao mesmo tempo outra garrafa, vindo a si, que ele foi premido a provar. Uma hora depois um médico declarou que ambos estavam envenenados por comer cogumelos. Spada morreu no limiar do vinhedo; o sobrinho expirou na sua própria porta, fazendo sinais que sua mulher não pôde compreender.

A seguir César e o papa se apressaram para botar as mãos na herança, sob o disfarce de estarem à procura de papéis do homem morto. Mas a herança consistia disso somente, um pedaço de papel em que Spada escreveu: -<Eu lego a meu amado sobrinho meus cofres, meus livros, e, entre outros, meu breviário com orelhas de ouro, que eu espero que ele preserve em consideração de seu querido tio.>

Os herdeiros procuraram em todo lugar, admiraram o breviário, se apropriaram dos móveis, e se espantaram grandemente de que Spada, o homem rico, era de fato o mais miserável dos tios – nenhum tesouro – e não ser que fossem os da ciência, contidos na biblioteca e laboratórios. Isso era tudo. César e seu pai procuraram, examinaram, escrutinaram, mas nada acharam, ou pelo menos muito pouco; nada que excedesse alguns milhares de coroas em prata, e aproximadamente o mesmo em dinheiro corrente; mas o sobrinho teve tempo de dizer a sua esposa, antes de morrer: <Procure direito entre os papéis do meu tio; há um testamento.>

Eles procuraram até mais meticulosamente do que os augustos herdeiros o fizeram, mas foi infrutífero. Havia dois palácios e um vinhedo atrás da Colina Palatina; mas nesses dias a propriedade da terra não tinha assim tanto valor, e os 2 palácios e o vinhedo continuaram com a família já que estavam abaixo da rapacidade do papa e seu filho. Meses e anos se passaram. Alexandre VI morreu, envenenado, – você sabe por qual erro. César, envenenado também, escapou desfolhando sua pele como a de uma cobra; mas a pele de baixo ficou marcada pelo veneno até se parecer com a de um tigre. Então, compelido a deixar Roma, ele acabou morto obscuramente numa escaramuça noturna; quase sem registros históricos. Depois da morte do papa e do exílio de seu filho, supôs-se que a família Spada voltaria ao esplendor dos tempos anteriores aos do cardeal; mas não foi o caso. Os Spada permaneceram em um conforto duvidoso, um mistério seguiu pairando sobre esse tema escuso, e o rumor público era que César, um político mais talentoso que seu pai, havia retirado do papa a fortuna dos 2 cardeais. Eu digo dos 2, porque o Cardeal Rospigliosi, que não tomara nenhuma precaução, foi completamente espoliado.”

“Eu estava então quase certo de que a herança não ficara nem para os Bórgias nem para a família, mas se mantivera sem dono como os tesouros das 1001 Noites, que dormiam no seio da terra sob os olhos do gênio.”

“esses caracteres foram traçados numa tinta misteriosa e simpática, que só aparecia ao ser exposta ao fogo; aproximadamente 1/3 do papel foi consumido pelas chamas.”

“<2 milhões de coroas romanas; quase 13 milhões, no nosso dinheiro.” [*]

[*] $2.600.000 em 1894.”

“Then an invincible and extreme terror seized upon him, and he dared not again press the hand that hung out of bed, he dared no longer to gaze on those fixed and vacant eyes, which he tried many times to close, but in vain – they opened again as soon as shut.”

“<They say every year adds half a pound to the weight of the bones,> said another, lifting the feet.”

“The sea is the cemetery of the Chateau d’If.”

“It was 14 years day for day since Dantes’ arrest.”

“At this period it was not the fashion to wear so large a beard and hair so long; now a barber would only be surprised if a man gifted with such advantages should consent voluntarily to deprive himself of them.”

“The oval face was lengthened, his smiling mouth had assumed the firm and marked lines which betoken resolution; his eyebrows were arched beneath a brow furrowed with thought; his eyes were full of melancholy, and from their depths ocasionally sparkled gloomy fires of misanthropy and hatred; his complexion, so long kept from the sun, had now that pale color which produces, when the features are encircled with black hair, the aristocratic beauty of the man of the north; the profound learning he had acquired had besided diffused over his features a refined intellectual expression; and he had also acquired, being naturally of a goodly stature, that vigor which a frame possesses which has so long concentrated all its force within himself.”

“Moreover, from being so long in twilight or darkness, his eyes had acquired the faculty of distinguishing objects in the night, common to the hyena and the wolf.”

“it was impossible that his best friend – if, indeed, he had any friend left – could recognize him; he could not recognize himself.”

“Fortunately, D. had learned how to wait; he had waited 14 years for his liberty, and now he was free he could wait at least 6 months or a year for wealth. Would he not have accepted liberty without riches if it had been offered him? Besides, were not those riches chimerical? – offspring of the brain of the poor Abbé Faria, had they not died with him?”

“The patron of The Young Amelia proposed as a place of landing the Island of Monte Cristo, which being completely deserted, and having neither soldiers nor revenue officers, seemed to have been placed in the midst of the ocean since the time of the heathen Olympus by Mercury, the god of merchants and robbers, classes of mankind which we in modern times have separated if not made distinct, but which antiquity appears to have included in the same category” Tal pai, tal filho: vejo que um Dumas citou o outro, cf. o destino me comandou saber, por estar lendo A Dama das Camélias em simultaneidade – Jr. dissera a dado ponto, também inicial, de sua narrativa que era bom e inteligente que ladrões e comerciantes possuíssem antigamente o mesmo Deus, e que isso não era simples contingência histórica… Até aí, pensava tratar-se de Mammon, comentando o espúrio estilo de vida judio.

“e qual solidão é mais completa, ou mais poética, que a de um navio flutuando isolado sobre as águas do mar enquanto reina a obscuridade da noite, no silêncio da imensidão, e sob o olhar dos Céus?”

“Nunca um viciado em jogo, cuja fortuna esteja em jogo num lance de dados, chegou a experimentar a angústia que sentiu Edmundo em meio a seus paroxismos de esperança.”

“<Em 2h,> ele disse, <essas pessoas vão partir mais ricas em 50 piastres cada, dispostas a arriscar novamente suas vidas só para conseguir outros 50; então retornarão com uma fortuna de 600 francos e desperdiçarão esse tesouro nalgum vilarejo, com aquele orgulho dos sultões e a insolência dos nababos.”

“a providência, que, ao limitar os poderes do homem, gratifica-o ao mesmo tempo com desejos insaciáveis.”

“<E agora,> ele exclamou, relembrando o conto do pescador árabe, que Faria relatou, <agora, abre-te sésamo!>”

“o pavor – aquele pavor da luz do dia que mesmo no deserto nos faz temer estarmos sendo vigiados e observados.”

“dentes brancos como os de um animal carnívoro”

“seu marido mantinha sua tocaia diária na porta – uma obrigação que ele executava com tanta mais vontade, já que o salvava de ter de escutar os murmúrios e lamentos da companheira, que nunca o viu sem dirigir amargas invectivas contra o destino”

“<And you followed the business of a tailor?>

<True, I was a tailor, till the trade fell off. It is so hot at Marseilles, that really I believe that the respectable inhabitants will in time go without any clothing whatever. But talking of heat, is there nothing I can offer you by way of refreshment?>”

“<Too true, too true!> ejaculated Caderousse, almost suffocated by the contending passions which assailed him, <the poor old man did die.>”

“Os próprios cães que perambulam sem abrigo e sem casa pelas ruas encontram mãos piedosas que oferecem uma mancheia de pão; e esse homem, um cristão, deviam permitir perecer de fome no meio de outros homens que se autodenominam cristãos? é terrível demais para acreditar. Ah, é impossível – definitivamente impossível!”

“Eu não consigo evitar ter mais medo da maldição dos mortos que do ódio dos vivos.”

“Hold your tongue, woman; it is the will of God.”

“Happiness or unhappiness is the secret known but to one’s self and the walls – walls have ears but no tongue”

“<Com isso então,> disse o abade, com um sorriso amargo, <isso então dá 18 meses no total. O que mais o mais devoto dos amantes poderia desejar?> Então ele murmurou as palavras do poeta inglês, <Volubilidade, seu nome é mulher.>”

“<no doubt fortune and honors have comforted her; she is rich, a countess, and yet–> Caderousse paused.”

Maneiras, maneiras de dizer asneiras…

Memorial de Buenos Aires

O aras à beira…

Bonaire de mademoiselle

Gastão amável que me acende o fogo!

ENCICLOPÉDIA DE UM FUTURO REMOTO

(…)

V

(…)

VANIGRACISMO [s.m., origem desconhecida; suspeita-se que guarde relação com vanitas, do latim <vaidade>]: espécie de atavismo do mal; inclinação ou tendência à reprise na crença de dogmas ultrapassados, como a pregação extremada do amor de Cristo ou o apego a regimes e práticas totalitários de forma geral. Duas faces do mesmo fenômeno. Nostalgia do Líder Supremo ou de coletivismos tornados impossíveis ou inexistentes nas democracias de massa, capitalismo avançado ou fase agônica do Ocidente.

Adeptos são identificados sob a alcunha de vanigra.

Ex:

Os vanigras brasileiros da década de 10 desejavam a conclamação de Bolsonaro como o Pai Nacional.

O vanigra praguejou seu semelhante com a condenação ao Inferno no seu pós-vida, graças a suas condutas imorais.

vanigger – Corruptela de vanigra, utilizada para designar negros conservadores que insultavam a memória e o passado histórico de seus ancestrais escravos, ao professarem credos como os supracitados (cristianismo, fascismo, etc.), invenções do homem branco europeu.

* * *

“In business, sir, said he, one has no friends, only correspondents”

“the tenacity peculiar to prophets of bad news”

“It was said at this moment that Danglars was worth from 6 to 8 millions of francs, and had unlimited credit.”

“Her innocence had kept her in ignorance of the dangers that might assail a young girl of her age.”

“And now, said the unknown, farewell kindness, humanity and gratitude! Farewell to all the feelings that expand the heart! I have been heaven’s substitute to recompense the good – now the god of vengeance yields me his power to punish the wicked!”

“in 5 minutes nothing but the eye of God can see the vessel where she lies at the bottom of the sea.”

“He was one of those men who do not rashly court danger, but if danger presents itself, combat it with the most unalterable coolness.”

“The Italian s’accommodi is untranslatable; it means at once <Como, enter, you are welcome; make yourself at home; you are the master.>”

“he was condemned by the by to have his tongue cut out, and his hand and head cut off; the tongue the 1st day, the hand the 2nd, and the head the 3rd. I always had a desire to have a mute in my service, so learning the day his tongue was cut out, I went to the bey [governador otomano], and proposed to give him for Ali a splendid double-barreled gun which I knew he was very desirous of having.”

“I? – I live the happiest life possible, the real life of a pasha. I am king of all creation. I am pleased with one place, and stay there; I get tired of it, and leave it; I am free as a bird and have wings like one; my attendants obey my slightest wish.”

“What these happy persons took for reality was but a dream; but it was a dream so soft, so voluptuous, so enthralling, that they sold themselves body and soul to him who have it to them, and obedient to his orders as to those of a deity, struck down the designated victim, died in torture without a murmur, believing that the death they underwent was but a quick transtion to that life of delights of which the holy herb, now before you, had given them a slight foretaste.”

“<Then,> cried Franz, <it is hashish! I know that – by name at least.>

<That it is precisely, Signor Aladdin; it is hashish – the purest and most unadulterated hashish of Alexandria, – the hashish of Abou-Gor, the celebrated maker, the only man, the man to whom there should be built a palace, inscribed with these words, <A grateful world to the dealer in happiness.>”

“Nature subdued must yield in the combat, the dream must succeed [suck-seed] to reality, and then the dream reigns supreme, then the dream becomes life, and life becomes the dream.”

“When you return to this mundane sphere from your visionary world, you would seem to leave a Neapolitan spring for a Lapland winter – to quit paradise for earth – heaven for hell! Taste the hashish, guest of mine – taste the hashish.”

“Tell me, the 1st time you tasted oysters, tea, porter, truffles, and sundry other dainties which you now adore, did you like them? Could you comprehend how the Romans stuffed their pheasants [faisões] with assafoetida (sic – asafoetida) [planta fétida, mas saborosa], and the Chinese eat swallow’s nests? [ninhos de andorinhas] Eh? no! Well, it is the same with hashish; only eat for a week, and nothing in the world will seem to you equal the delicacy of its flavor, which now appears to you flat and distasteful.”

“there was no need to smoke the same pipe twice.”

“that mute revery, into which we always sink when smoking excellent tobacco, which seems to remove with its fume all the troubles of the mind, and to give the smoker in exchange all the visions of the soul. Ali brought in the coffee. <How do you take it?> inquired the unknown; <in the French or Turkish style, strong or weak, sugar or none, coal or boiling? As you please; it is ready in all ways.>”

“it shows you have a tendency for an Oriental life. Ah, those Orientals; they are the only men who know how to live. As for me, he added, with one of those singular smiles which did not escape the young man, when I have completed my affairs in Paris, I shall go and die in the East; and should you wish to see me again, you must seek me at Cairo, Bagdad, or Ispahan.”

“Well, unfurl your wings, and fly into superhuman regions; fear nothing, there is a watch over you; and if your wings, like those of Icarus, melt before the sun, we are here to ease your fall.”

o tempo é testemunha

1001 Noites

The Count of Sinbad Cristo

“Oh, ele não teme nem Deus nem Satã, dizem, e percorreria 50 ligas fora de seu curso só para prestar um favor a qualquer pobre diabo.”

“em Roma há 4 grandes eventos todos os anos, – o Carnaval, a Semana Santa, Corpus Christi, o Festival de São Pedro. Durante todo o resto do ano a idade está naquele estado de apatia profunda, entre a vida e a morte, que a deixa parecida com uma estação entre esse mundo e o próximo”

“<Para São Pedro primeiro, e depois o Coliseu,> retorquiu Albert. Mas Albrto não sabia que leva um dia para ver [a Basílica de] S. Pedro, e um mês para estudá-la. O dia foi todo passado lá.”

“Quando mostramos a um amigo uma cidade que já visitamos, sentimos o mesmo orgulho de quando apontamos na rua uma mulher da qual fomos o amante.”

“mulher amantizada”, aliás (livro de Dumas Filho) é o melhor eufemismo de todos os tempos!

“<em Roma as coisas podem ou não podem ser feitas; quando se diz que algo não pode ser feito, acaba ali>

<É muito mais conveniente em Paris, – quando qualquer coisa não pode ser feita, você paga o dobro, e logo ela está feita.>

<É o que todo francês fala,> devolveu o Signor Pastrini, que acusou o golpe; <por essa razão, não entendo por que eles viajam.> (…)

<Homens em seu juízo perfeito não deixam seu hotel na Rue du Helder, suas caminhadas no Boulevard de Grand, e Café de Paris.>”

“<Mas se vossa excelência contesta minha veracidade> – <Signor Pastrini,> atalhou Franz, <você é mais suscetível que Cassandra, que era uma profetisa, e ainda assim ninguém acreditava nela; enquanto que você, pelo menos, está seguro do crédito de metade de sua audiência [a metade de 2 é 1]. Venha, sente-se, e conte-nos tudo que sabe sobre esse Signor Vampa.>”

“<O que acha disso, Albert? – aos 2-e-20 ser tão famoso?>

<Pois é, e olha que nessa idade Alexandre, César e Napoleão, que, todos, fizeram algum barulho no mundo, estavam bem detrás dele.>”

“Em todo país em que a independência tomou o lugar da liberdade, o primeiro desejo dum coração varonil é possuir uma arma, que de uma só vez torna seu dono capaz de se defender e atacar, e, transformando-o em alguém terrível, com freqüência o torna temido.”

“O homem de habilidades superiores sempre acha admiradores, vá onde for.”

MÁFIA: SEQÜESTRO, ESTUPRO, MORTE & A SUCESSÃO DO CLÃ

“As leis dos bandidos [dos fora-da-lei] são positivas; uma jovem donzela pertence ao primeiro que levá-la, então o restante do bando deve tirar a sorte, no que ela é abandonada a sua brutalidade até a morte encerrar seus sofrimentos. Quando seus pais são suficientemente ricos para pagar um resgate, um mensageiro é enviado para negociar; o prisioneiro é refém pela segurança do mensageiro; se o resgate for recusado, o refém está irrevogavelmente perdido.”

“Os mensageiros naturais dos bandidos são os pastores que habitam entre a cidade e as montanhas, entre a vida civilizada e a selvagem.”

“<Tiremos a sorte! Tiremos a sorte!> berraram todos os criminosos ao verem o chefe. Sua demanda era justa e o chefe reclinou a cabeça em sinal de aprovação. Os olhos de todos brilharam terrivelmente, e a luz vermelha da fogueira só os fazia parecer uns demônios. O nome de cada um incluído o de Carlini, foi colocado num chapéu, e o mais jovem do bando retirou um papel; e ele trazia o nome de Diovolaccio¹. Foi ele quem propôs a Carlini o brinde ao chefe, e a quem Carlini reagiu quebrando o copo na sua cara. Uma ferida enorme, da testa à boca, sangrava em profusão. Diovolaccio, sentindo-se favorecido pela fortuna, explodiu em uma gargalhada. <Capitão,> disse, <ainda agora Carlini não quis beber à vossa saúde quando eu propus; proponha a minha a ele, e veremos se ele será mais condescendente consigo que comigo.> Todos aguardavam uma explosão da parte de Carlini; mas para a surpresa de todos ele pegou um copo numa mão e o frasco na outra e, enchendo o primeiro, – <A sua saúde, Diavolaccio²,> pronunciou calmamente, e ele entornou tudo, sem que sua mão sequer tremesse. (…) Carlini comeu e bebeu como se nada tivesse acontecido. (…) Uma faca foi plantada até o cabo no peito esquerdo de Rita. Todos olharam para Carlini; a bainha em seu cinto estava vazia. <Ah, ah,> disse o chefe, <agora entendo por que Carlini ficou para trás.> Todas as naturezas selvagens apreciam uma ação desesperada. Nenhum outro dos bandidos, talvez, fizesse o mesmo; mas todos entenderam o que Carlini fez. <Agora, então,> berrou Carlini, levantando-se por sua vez, aproximando-se do cadáver, sua mão na coronha de uma de suas pistolas, <alguém disputa a posse dessa mulher comigo?> – <Não,> respondeu o chefe, <ela é tua.>”

¹ Corruptela de demônio em Italiano

² Aqui o interlocutor, seu inimigo desde o sorteio, pronuncia o nome como o substantivo correto: diabo, demônio.

“<Cucumetto violentou sua filha,> disse o bandido; <eu a amava, destarte matei-a; pois ela serviria para entreter a quadrilha inteira.> O velho não disse nada mas empalideceu como a morte. <Então,> continuou, <se fiz mal, vingue-a;>”

“Mas Carlini não deixou a floresta sem saber o paradeiro do pai de Rita. Foi até o lugar onde o deixara na noite anterior. E encontrou o homem suspenso por um dos galhos, do mesmo carvalho que ensombreava o túmulo de sua filha. Então ele fez um amargo juramento de vingança sobre o corpo morto de uma e debaixo do corpo do outro. No entanto, Carlini não pôde cumprir sua promessa, porque 2 dias depois, num encontro com carabineiros romanos, Carlini foi assassinado. (…) Na manhã da partida da floresta de Frosinone Cucumetto seguiu Carlini na escuridão, escutou o juramento cheio de ódio, e, como um homem sábio, se antecipou a ele. A gente contou outras dez histórias desse líder de bando, cada uma mais singular que a anterior. Assim, de Fondi a Perusia, todo mundo treme ao ouvir o nome de Cucumetto.”

“Cucumetto era um canalha inveterado, que assumiu a forma de um bandido ao invés de uma cobra nesta vida terrana. Como tal, ele adivinhou no olhar de Teresa o signo de uma autêntica filha de Eva, retornando à floresta, interrompendo-se inúmeras vezes sob pretexto de saudar seus protetores. Vários dias se passaram e nenhum sinal de Cucumetto. Chegava a época do Carnaval.”

“4 jovens das mais ricas e nobres famílias de Roma acompanhavam as 3 damas com aquela liberdade italiana que não tem paralelo em nenhum outro país.”

“Luigi sentia ciúmes! Ele sentiu que, influenciada pela sua disposição ambiciosa e coquete, Teresa poderia escapar-lhe.”

“Por que, ela não sabia, mas ela não sentia minimamente que as censuras de seu amado fossem merecidas.”

“<Teresa, o que você estava pensando enquanto dançava de frente para a jovem Condessa de San-Felice?> – <Eu estava pensando,> redargüiu a jovem, com toda a franqueza que lhe era natural, <que daria metade da minha vida por um vestido como o dela.>

“<Luigi Vampa,> respondeu o pastor, com o mesmo ar daquele que se apresentasse Alexandre, Rei da Macedônia.

<E o seu?> – <Eu,> disse o viajante, <sou chamado Sinbad, o Marinheiro.>

Franz d’Espinay fitou surpreso.”

“Sim, mas eu vim pedir mais do que ser vosso companheiro.> – <E o que poderia ser isso?> inquiriram os bandidos, estupefatos. – <Venho solicitar ser vosso capitão,> disse o jovem. Os bandidos fizeram uma arruaça de risadas. <E o que você fez para aspirar a essa honra?> perguntou o tenente. – <Matei seu chefe, Cucumetto, cujo traje agora visto; e queimei a fazenda San-Felice para pegar o vestido-de-noiva da minha prometida.> Uma hora depois Luigi Vampa era escolhido capitão, vice o finado Cucumetto.”

* * *

Minha casa não seria tão boa se o mundo lá fora não fosse tão ruim.

A vingança tem de começar nalgum lugar: a minha começa no cyberrealm, aqui.

“nem é possível, em Roma, evitar essa abundante disposição de guias; além do ordinário cicerone, que cola em você assim que pisa no hotel, e jamais o deixa enquanto permanecer na cidade, há ainda o cicerone especial pertencente a cada monumento – não, praticamente a cada parte de um monumento.”

“só os guias estão autorizados a visitar esses monumentos com tochas nas mãos.”

“Eu disse, meu bom companheiro, que eu faria mais com um punhado de ouro numa das mãos que você e toda sua tropa poderiam produzir com suas adagas, pistolas, carabinas e canhões incluídos.”

“E o que tem isso? Não está um dia dividido em 24h, cada hora em 60 minutos, e todo minuto em 60 segundos? Em 86.400 segundos muita coisa pode acontecer.”

“Albert nunca foi capaz de suportar os teatros italianos, com suas orquestras, de onde é impossível ver, e a ausência de balcões, ou camarotes abertos; todos esses defeitos pesavam para um homem que tinha tido sua cabine nos Bouffes, e usufruído de um camarote baixo na Opera.”

“Albert deixou Paris com plena convicção de que ele teria apenas de se mostrar na Itáia para ter todos a seus pés, e que em seu retorno ele espantaria o mundo parisiano com a recitação de seus numerosos casos. Ai dele, pobre Albert!”

“e tudo que ele ganhou foi a convicção dolorosa de que as madames da Itália têm essa vantagem sobre as da França, a de que são fiéis até em sua infidelidade.”

“mas hoje em dia ão é preciso ir tão longe quanto a Noé ao traçar uma linhagem, e uma árvore genealógica é igualmente estimada, date ela de 1399 ou apenas 1815”

“A verdade era que os tão aguardados prazeres do Carnaval, com a <semana santa> que o sucederia, enchia cada peito de tal forma que impedia que se prestasse a menor atenção aos negócios no palco. Os atores entravam e saíam despercebidos e ignorados; em determinados momentos convencionais, os expectadores paravam repentinamente suas conversas, ou interrompiam seus divertimentos, para ouvir alguma performance brilhante de Moriani, um recitativo bem-executado por Coselli, ou para aplaudir em efusão os maravilhosos talentos de La Specchia”

“<Oh, she is perfectly lovely – what a complexion! And such magnificent hair! Is she French?>

<No, Venetian.>

<And her name is–>

<Countess G——.>

<Ah, I know her by name!> exclaimed Albert; <she is said to possess as much wit and cleverness as beauty. I was to have been presented to her when I met her at Madame Villefort’s ball.>”

“believe me, nothing is more fallacious than to form any estimate of the degree of intimacy you may suppose existing among persons by the familiar terms they seem upon”

“Por mais que o balé pudesse atrair sua atenção, Franz estava profundamente ocupado com a bela grega para se permitir distrações”

“Graças ao judicioso plano de dividir os dois atos da ópera com um balé, a pausa entre as performances é muito curta, tendo os cantores tempo de repousar e trocar de figurino, quando necessário, enquanto os dançarinos executam suas piruetas e exibem seus passos graciosos.”

“Maioria dos leitores está ciente [!] de que o 2º ato de <Parisina> abre com um celebrado e efetivo dueto em que Parisina, enquanto dorme, se trai e confessa a Azzo o segredo de seu amor por Ugo. O marido injuriado passa por todos os paroxismos do ciúme, até a firmeza prevalecer em sua mente, e então, num rompante de fúria e indignação, ele acordar sua esposa culpada para contar-lhe que ele sabe de seus sentimentos, e assim infligir-lhe sua vingança. Esse dueto é um dos mais lindos, expressivos e terríveis de que jamais se ouviu emanar da pena de Donizetti. Franz ouvia-o agora pela 3ª vez.”

“<Talvez você jamais tenha prestado atenção nele?>

<Que pergunta – tão francesa! Não sabe você que nós italianas só temos olhos para o homem que amamos?>

<É verdade,> respondeu Franz.”

“<he looks more like a corpse permitted by some friendly grave-digger to quit his tomb for a while, and revisit this earth of ours, than anything human. How ghastly pale he is!>

<Oh, he is always as colorless as you now see him,> said Franz.

<Then you know him?> almost screamed the countess. <Oh, pray do, for heaven’s sake, tell us all about – is he a vampire, or a ressuscitated corpse, or what?>

<I fancy I have seen him before, and I even think he recognizes me.>”

“Vou dizer-lhe, respondeu a condessa. Byron tinha a mais sincera crença na existência de vampiros, e até assegurou a mim que os tinha visto. A descrição que ele me fez corresponde perfeitamente com a aparência e a personalidade daquele homem na nossa frente. Oh, ele é a exata personificação do que eu poderia esperar. O cabelo cor-de-carvão, olhos grandes, claros e faiscantes, em que fogo selvagem, extraterreno parece queimar, — a mesma palidez fantasmal. Observe ainda que a mulher consigo é diferente de qualquer uma do seu sexo. Ela é uma estrangeira – uma estranha. Ninguém sabe quem é, ou de onde ela vem. Sem dúvida ela pertence à mesma raça que ele, e é, como ele, uma praticante das artes mágicas.”

“Pela minha alma, essas mulheres confundiriam o próprio Diabo que quisesse desvendá-las. Porque, aqui – elas lhe dão sua mão – elas apertam a sua em correspondência – elas mantêm conversas em sussurros – permitem que você as acompanhe até em casa. Ora, se uma parisiense condescendesse com ¼ dessas coqueterias, sua reputação estaria para sempre perdida.”

“Ele era talvez bem pálido, decerto; mas, você sabe, palidez é sempre vista como uma forte prova de descendência aristocrática e casamentos distintos.”

“e, a não ser que seu vizinho de porta e quase-amigo, o Conde de Monte Cristo, tivesse o anel de Gyges, e pelo seu poder pudesse ficar invisível, agora era certo que ele não poderia escapar dessa vez.”

“O Conde de Monte Cristo é sempre um levantado cedo da cama; e eu posso assegurar que ele já está de pé há duas horas.”

“You are thus deprived of seeing a man guillotined; but the mazzuola still remains, which is a very curious punishment when seen for the 1st time, and even the 2nd, while the other, as your must know, is very simple.” [Ver glossário acima.]

“do not tell me of European punishments, they are in the infancy, or rather the old age, of cruelty.”

“As for myself, I can assure you of one thing, — the more men you see die, the easier it becomes to die yourself” opinion opium onion

“do you think the reparation that society gives you is sufficient when it interposes the knife of the guillotine between the base of the occiput and the trapezal muscles of the murderer, and allows him who has caused us years of moral sufferings to escape with a few moments of physical pain?”

“Dr. Guillotin got the idea of his famous machine from witnessing an execution in Italy.”

“We ought to die together. I was promissed he should die with me. You have no right to put me to death alone. I will not die alone – I will not!”

“Oh, man – race of crocodiles, cried the count, extending his clinched hands towards the crowd, how well do I recognize you there, and that at all times you are worthy of yourselves! Lead two sheep to the butcher’s, 2 oxen to the slaughterhouse, and make one of them understand that his companion will not die; the sheep will bleat for pleasure, the ox will bellow with joy. But man – man, whom God has laid his first, his sole commandment, to love his neighbor – man, to whom God has given a voice to express his thoughts – what is his first cry when he hears his fellowman is saved? A blasphemy. Honor to man, this masterpiece of nature, this king of creation! And the count burst into a laugh; a terrible laugh, that showed he must have suffered horribly to be able thus to laugh.”

“The bell of Monte Citorio, which only sounds on the pope’s decease and the opening of the Carnival, was ringing a joyous peal.”

“On my word, said Franz, you are wise as Nestor and prudent as Ulysses, and your fair Circe must be very skilful or very powerful if she succeed in changing you into a beast of any kind.”

“Come, observed the countess, smiling, I see my vampire is only some millionaire, who has taken the appearance of Lara in order to avoid being confounded with M. de Rothschild; and you have seen her?”

“without a single accident, a single dispute, or a single fight. The fêtes are veritable pleasure days to the Italians. The author of this history, who has resided 5 or 6 years in Italy, does not recollect to have ever seen a ceremony interrupted by one of those events so common in other countries.”

“Se alle sei della mattina le quattro mile piastre non sono nelle mie mani, alla sette il conte Alberto avra cessato di vivere.

Luigi Vampa.”

“There were in all 6.000 piastres, but of these 6.000 Albert had already expended 3.000. As to Franz, he had no better of credit, as he lived at Florence, and had only come to Rome to pass 7 or 8 days; he had brought but a 100 louis, and of these he had not more than 50 left.”

“Well, what good wind blows you hither at this hour?”

“I did, indeed.”

“Be it so. It is a lovely night, and a walk without Rome will do us both good.”

“<Excellency, the Frenchman’s carriage passed several times the one in which was Teresa.>

<The chief’s mistress?>

<Yes. The Frenchman threw her a bouquet; Teresa returned it – all this with the consent of the chief, who was in the carriage.>

<What?> cried Franz, <was Luigi Vampa in the carriage with the Roman peasants?>”

“Well, then, the Frenchman took off his mask; Teresa, with the chief’s consent, did the same. The Frenchman asked for a rendez-vous; Teresa gave him one – only, instead of Teresa, it was Beppo who was on the steps of the church of San Giacomo.”

“<do you know the catacombs of St. Sebastian?>

<I was never in them; but I have often resolved to visit them.>

<Well, here is an opportunity made to your hand, and it would be difficult to contrive a better.>”

“remember, for the future, Napoleon’s maxim, <Never awaken me but for bad news;> if you had let me sleep on, I should have finished my galop [dança de salão], and have been grateful to you all my life.”

“<Has your excellency anything to ask me?> said Vampa with a smile.

<Yes, I have,> replied Franz; <I am curious to know what work you were perusing with so much attention as we entered.>

<Caesar’s ‘Commentaries,’> said the bandit, <it is my favorite work.>”

“não há nação como a francesa que possa sorrir mesmo na cara da terrível Morte em pessoa.”

“Apenas pergunte a si mesmo, meu bom amigo, se não acontece com muitas pessoas de nosso estrato que assumam nomes de terras e propriedades em que nunca foram senhores?”

“a vista do que está acontecendo é necessária aos homens jovens, que sempre estão dispostos a ver o mundo atravessar seus horizontes, mesmo se esse horizonte é só uma via pública.”

“foils, boxing-gloves, broadswords, and single-sticks – for following the example of the fashionable young men of the time, Albert de Morcerf cultivated, with far more perseverance than music and drawing, the 3 arts that complete a dandy’s education, i.e., fencing [esgrima], boxing, and single-stick”

“In the centre of the room was a Roller and Blanchet <baby grand> piano in rosewood, but holding the potentialities of an orchestra in its narrow and sonorous cavity, and groaning beneath the weight of the chefs-d’oeuvre of Beethoven, Weber, Mozart, Haydn, Gretry, and Porpora.”

“There on a table, surrounded at some distance by a large and luxurious divan, every species of tobacco known, – from the yellow tobacco of Petersburg to the black of Sinai, and so on along the scale from Maryland and Porto-Rico, to Latakia, – was exposed in pots of crackled earthenware [cerâmica] of which the Dutch are so fond; beside them, in boxes of fragrant wood, were ranged, according to their size and quality, pueros, regalias, havanas, and manillas; and, in an open cabinet, a collection of German pipes, of chibouques [cachimbo turco], with their amber mouth-pieces ornamented with coral, and of narghilés, with their long tubes of morocco, awaiting the caprice of the sympathy of the smokers.”

“after coffee, the guests at a breakfast of modern days love to contemplate through the vapor that escapes from their mouths, and ascends in long and fanficul wreaths to the ceiling.”

A única diferença entre Jesus Cristo e eu é que uma cruz o carregava – eu é que carrego a minha cruz.

“<Are you hungry?>

<Humiliating as such a confession is, I am. But I dined at M. de Villefort’s, and lawyers always give you very bad dinners. You would think they felt some remorse; did you ever remark that?>

<Ah, depreciate other persons’ dinners; you ministers give such splendid ones.>”

“<Willingly. Your Spanish wine is excellent. You see we were quite right to pacify that country.>

<Yes, but Don Carlos?>

<Well, Don Carlos will drink Bordeaux, and in years we will marry his son to the little queen.>”

“Recollect that Parisian gossip has spoken of a marriage between myself and Mlle. Eugenie Danglars”

“<The king has made him a baron, and can make him a peer [cavalheiro], but he cannot make him a gentleman, and the Count of Morcerf is too aristocratic to consent, for the paltry sum of 2 million francs to a mesalliance [‘desaliança’, casamento com um malnascido]. The Viscount of Morcerf can only wed a marchioness.>

<But 2 million francs make a nice little sum,> replied Morcerf.”

“<Nevermind what he says, Morcerf,> said Debray, <do you marry her. You marry a money-bag label, it is true; well but what does that matter? It is better to have a blazon less and a figure more on it. You have seven martlets on your arms; give 3 to your wife, and you will still have 4; that is 1 more than M. de Guise had, who so nearly became King of France, and whose cousin was emperor of Germany.>”

“além do mais, todo milionário é tão nobre quanto um bastardo – i.e., ele pode ser.”

“<M. de Chateau-Renaud – M. Maximilian Morrel,> said the servant, announcing 2 fresh guests.”

“a vida não merece ser falada! – isso é um pouco filosófico demais, minha palavra, Morrel. Fica bem para você, que arrisca sua vida todo dia, mas para mim, que só o fez uma vez—“

“<No, his horse; of which we each of us ate a slice with a hearty appetite. It was very hard.>

<The horse?> said Morcerf, laughing.

<No, the sacrifice,> returned Chateau-Renaud; <ask Debray if he would sacrifice his English steed for a stranger?>

<Not for a stranger,> said Debray, <but for a friend I might, perhaps.>”

“hoje vamos encher nossos estômagos, e não nossas memórias.”

“<Ah, this gentleman is a Hercules killing Cacus, a Perseus freeing Andromeda.>

<No, he is a man about my own size.>

<Armed to the teeth?>

<He had not even a knitting-needle [agulha de tricô].>”

“He comes possibly from the Holy Land, and one of his ancestors possessed Calvary, as the Mortemarts(*) did the Dead Sea.”

(*) Wiki: “Anne de Rochechouart de Mortemart (1847-1933), duchess of Uzès, held one of the biggest fortunes in Europe, spending a large part of it on financing general Boulanger’s political career in 1890. A great lady of the world, she wrote a dozen novels and was the 1st French woman to possess a driving licence.”

Motto: “Avant que la mer fût au monde, Rochechouart portait les ondes”

“<he has purchased the title of count somewhere in Tuscany?>

<He is rich, then?>

<Have you read the ‘Arabian Nights’?>

<What a question!>”

“he calls himself Sinbad the Sailor, and has a cave filled with gold.”

“<Pardieu, every one exists.>

<Doubtless, but in the same way; every one has not black salves, a princely retinue, an arsenal of weapons that would do credit to an Arabian fortress, horses that cost 6.000 francs apiece, and Greek mistresses.>”

“<Did he not conduct you to the ruins of the Colosseum and suck your blood?> asked Beauchamp.

<Or, having delivered you, make you sign a flaming parchment, surrendering your soul to him as Esau did his birth-right?>”

“The count appeared, dressed with the greatest simplicity, but the most fastidious dandy could have found nothing to cavil [escarnecer] at in his toilet. Every article of dress – hat, coat, gloves, and boots – was from the 1st makers. He seemed scarcely five-and-thirty. But what struck everybody was his extreme resemblance to the portrait Debray had drawn.”

“Punctuality,> said M. Cristo, <is the politeness of kings, according to one of your sovereings, I think; but it is not the same with travellers. However, I hope you will excuse the 2 or 3 seconds I am behindhand; 500 leagues are not to be accomplished without some trouble, and especially in France, where, it seems, it is forbidden to beat the postilions [cocheiros].”

“a traveller like myself, who has successively lived on maccaroni at Naples, polenta at Milan, olla podrida¹ at Valencia, pilau at Constantinople, karrick in India, and swallow’s nests in China. I eat everywhere, and of everything, only I eat but little”

¹ olla podrida: cozido com presunto, aves e embutidos.a

a embutido: carne de tripa

“<But you can sleep when you please, monsieur?> said Morrel.

<Yes>

<You have a recipe for it?>

<An infallible one.>

(…)

<Oh, yes, returned M.C.; I make no secret of it. It is a mixture of excellent opium, which I fetched myself from Canton in order to have it pure, and the best hashish which grows in the East – that is, between the Tigris and the Euphrates.>”

“he spoke with so much simplicity that it was evident he spoke the truth, or that he was mad.”

“<Perhaps what I am about to say may seem strange to you, who are socialists, and vaunt humanity and your duty to your neighbor, but I never seek to protect a society which does not protect me, and which I will even say, generally occupies itself about me only to injure me; and thus by giving them a low place in my steem, and preserving a neutrality towards them, it is society and my neighbor who are indebted to me.>

(…) <you are the 1st man I ever met sufficiently courageous to preach egotism. Bravo, count, bravo!>” “vocês assumem os vícios que não têm, e escondem as virtudes que possuem.”

“France is so prosaic, and Paris so civilized a city, that you will not find in its 85 departments – I say 85, because I do not include Corsica – you will not find, then, in these 85 departments a single hill on which there is not a telegraph, or a grotto in which the comissary of polie has not put up a gaslamp.”

“<But how could you charge a Nubian to purchase a house, and a mute to furnish it? – he will do everything wrong.>

<Undeceive yourself, monsieur,> replied M.C.; <I am quite sure, that o the contrary, he will choose everything as I wish. He knows my tastes, my caprices, my wants. He has been here a week, with the instinct of a hound, hunting by himself. He will arrange everything for me. He knew, that I should arrive to-day at 10 o’clock; he was waiting for me at 9 at the Barrière de Fontainebleau. He gave me this paper; it contains the number of my new abode; read it yourself,> and M.C. passed a paper to Albert. <Ah, that is really original.> said Beauchamp.”

“The young men looked at each other; they did not know if it was a comedy M.C. was playing, but every word he uttered had such an air of simplicity, that it was impossible to suppose what he said was false – besides, why whould he tell a falsehood?”

“<Eu, em minha qualidade de jornalista, abro-lhe todos os teatros.>

<Obrigado, senhor,> respondeu M.C., <meu mordomo tem ordens para comprar um camarote em cada teatro.>

<O seu mordomo é também um núbio?> perguntou Debray.

<Não, ele é um homem do campo europeu, se um córsico for considerado europeu. Mas você o conhece, M. de Morcerf.>

<Seria aquele excepcional Sr. Bertuccio, que entende de reservar janelas tão bem?>

<Sim, você o viu o dia que eu tive a honra de recebê-lo; ele tem sido soldado, bandido – de fato, tudo. Eu não teria tanta certeza de que nesse meio-tempo ele não teve problemas com a polícia por alguma briguinha qualquer – uma punhalada com uma faca, p.ex.>”

“Eu tenho algo melhor que isso; tenho uma escrava. Vocês procuram suas mulheres em óperas, o Vaudeville, ou as Variedades; eu comprei a minha em Constantinopla; me custa mais, mas não tenho do que reclamar.”

“It was the portrait of a young woman of 5-or-6-and-20, with a dark complexion, and light and lustrous eyes, veiled beneath long lashes. She wore the picturesque costume of the Catalan fisher-women, a red and black bodice and golden pins in her hair. She was looking at the sea, and her form was outlined on the blue ocean and sky. The light was so faint in the room that Albert did not perceive the pallor that spread itself over the count’s visage, or the nervous heaving of his chest and shoulders. Silence prevailed for an instant, during which M.C. gazed intently on the picture. § <You have there a most charming mistress, viscount,> said the count in a perfectly calm tone”

“Ah, monsieur, returned Albert, You do not know my mother; she it is whom you see here. She had her portrait painted thus 6 or 8 years ago. This costume is a fancy one, it appears, and the resemblance is so great that I think I still see my mother the same as she was in 1830. The countess had this portrait painted during the count’s absence.”

“The picture seems to have a malign influence, for my mother rarely comes here without looking at it, weeping. This disagreement is the only one that has ever taken place between the count and countess, who are still as much united, although married more than 20 years, as on the 1st day of their wedding.”

“Your are somewhat blasé. I know, and family scenes have not much effect on Sinbad the Sailor, who has seen so much many others.”

“These are our arms, that is, those of my father, but they are, as you see, joined to another shield, which has gules, a silver tower, which are my mother’s. By her side I am Spanish, but the family of Morcerf is French, and, I have heard, one of the oldest of the south of France.”

“<Yes, you are at once from Provence and Spain; that explains, if the portrait you showed me be like, the dark hue I so much admired on the visage of the noble Catalan.> It would have required the penetration of Oedipus or the Sphinx to have divined the irony the count concealed beneath these words, apparently uttered with the greatest politeness.”

“A gentleman of high birth, possessor of an ample fortune, you have consented to gain your promotion as an obscure soldier, step by step – this is uncommon; then become general, peer of France, commander of the Legion of Honor, you consent to again commence a 2nd apprenticeship, without any other hope or any other desire than that of one day becoming useful to your fellow-creatures”